Textual sources for Burgundian Black, Research Library Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. A film by Katrien Vanagt and Stefano Bertacchini, 2020 @Serafín Productions for ARTECHNE.

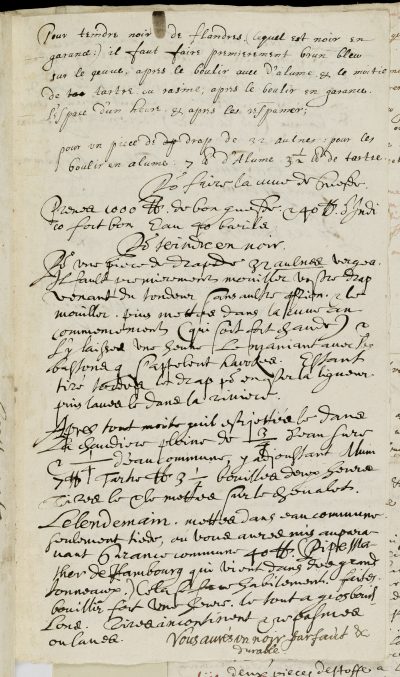

In 1646 a London dyer of good reputation shared his secret for the ‘Black of Flanders’ (‘Noir de Flandres‘) with an avid collector of colour-making recipes.[1] Drawn from the mouth of Pierre de Lanoy, a descendant of a family of Flemish dyers,[2] it is perhaps one of the most vivid written testimonies that we have today of the high art of black dyeing which flourished in the Burgundian Netherlands in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. [Figure 1]

The collector of this recipe was Sir Theodore de Mayerne (1573-1655), early modern Europe’s most famous court physician, who is mostly remembered today for his contributions to the study of arts and crafts rather than his voluminous medical legacy.[3] His keen interest in colour-making technologies and his pioneering work in documenting the colour knowledge of his time was shared by the first fellows of the Royal Society who eagerly studied, reworked, and archived the recipes that Mayerne collected, tried and discussed with artists and craftsmen.[4] This recipe, a handwritten paper dating from the mid-seventeenth century that has survived in the archives of the Royal Society of Science in London, testifies to a long tradition of colour researchers who were themselves no artisans, but who collected recipes to study the colour knowledge embodied in them.

With the recipe research for this book, we followed in Mayerne’s footsteps, studying black colour making technologies with natural colourants that were mastered in northern Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries under Burgundian-Habsburg reign. Through recipe reworkings with an interdisciplinary team of researchers, and the insights of renowned textile artist Claudy Jongstra and her team, we set out to explore the secrets of the black of Flanders, trying with all our senses to grasp the past colour worlds faded into oblivion with the rise of synthetic colour industries.

Burgundian Black

Mayerne’s note on the bottom of the recipe for Noir de Flandres promises that ‘you will have a perfect and durable black’ [Figure 3 (detail)].[5] As they describe in their contribution to this book, Natalia Ortega Saez and Vincent Cattersel, we attempted to reproduce this and other dye recipes, and they mention a variety of historic colour names for black and discuss different black dye technologies that were known and practiced in premodern Europe; re-workings of early modern dye-recipes also show that the colour black related to a palette of different hues and shades depending on the material to be dyed, the colourants used, and the dyeing procedure. In Europe, knowledge of dyeing high-quality durable black textiles can be traced back to the late Middle Ages. Archival records from guild regulations, ordinances, and ducal expenses for black dress from the fifteenth century show that master dyers in Burgundian-Habsburg dominions (c. 1364 -1580s)[6] had perfected the art of dyeing dark and intense tones of black. The rich, vibrant, and lustrous black shades that dyers attained in this period were unprecedented in northern Europe, as was the rising demand for luxury black clothing. In medieval Europe it had hardly been possible for dyers to attain deeply saturated black hues with the then known techniques and the commonly used local materials. Up to the fourteenth century, it remained difficult to dye black textiles evenly, and dark-coloured cloth lacked the vibrant qualities of expensive red fabrics coloured with the precious and highly concentrated red dyestuffs that dyers had access to through Europe’s trade centers. Black shades apparently tended towards greyish, murky hues, too close to the commoner’s poor-quality textiles to appeal to the higher echelons of late feudal societies. With the professionalization and specialization of dye plant cultivation and dyestuff production and the rise of textile trade guilds in charge of quality control, the knowledge and mastery of dye techniques improved to meet the growing demand for lightfast coloured textiles.[7] In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, if not earlier, an expensive and labour-intensive two-phase plant dye technology that combined and augmented the mastery of red dyers and blue dyers had been perfected in Flanders textile centers with direct access to high-quality dyestuff. Flemish dyers became famed throughout Europe for their production of the finest black broadcloth (‘vlaamsch zwart laken’).[8]

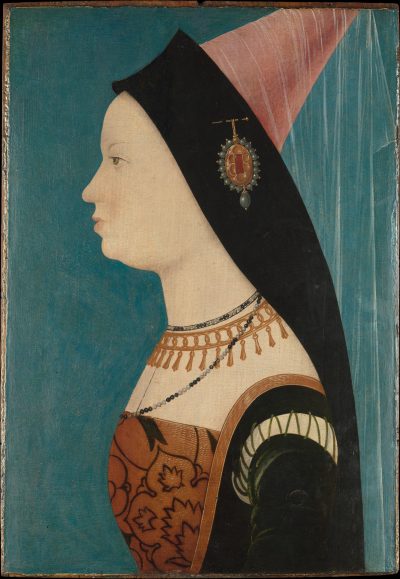

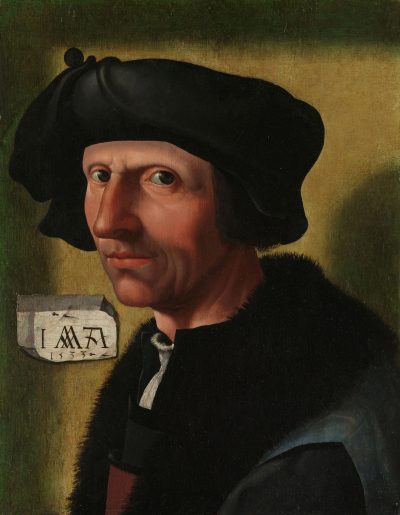

The rise of black as a fashionable colour among late medieval and early modern Europe’s urban patriciate, nobility, and the curia alike started in the fourteenth century, but under the rule of Philip the Good Duke of Burgundy (1396-1467) [Figure 4] and his Hapsburg heirs, Mary of Burgundy (1457-1482) who married Maximilian I (1459-1519), the later Holy Roman Emperor, black dress became a sign of luxury and the true colour of secular and religious power [Figure 5] (see Sophie Jolivet’s and Paula Hohti’s contributions to this book).[9] The most fashionable colour at the Burgundian-Habsburg court set the tone for the rest of early modern Europe. In the sixteenth century the taste for sumptuous black dress flourished under the rule of Mary and Maximilian’s daughter Margaret of Austria (1480 – 1530), their grandson, Charles V (1500-1558), and the latter’s daughter Maria of Austria (1528 – 1603) and son Philip II (1527-1598), King of Spain and a pronounced devotee of black dress [Figures 6 and 7].[10] But in Renaissance Europe black became not only the colour of ruling elites. Unhindered by sumptuary laws, a widespread use of black clothing can be observed among lower social classes, as Hohti Erichsen points out elsewhere in this book: from the sixteenth century onwards not only the higher echelons of society, but also members of the middling ranks could now afford to play on chromatic connotations of authority and dignity.

Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Alte Pinakothek, Munich, https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/RQ4XP7p410

@CC BY-SA 4.0

When Mayerne got his hands on the secret for dyeing the black of Flanders (‘pour teindre Noir de Flandres‘) with blue and red plant dyes in the mid-seventeenth century, this expensive and labour-intensive dye technology had already been superseded by new ways of black dyeing brought on by gradually declining guild restrictions and an unprecedented influx of (new) dyestuff from overseas; this development caused the once-precious dyer’s knowledge of ‘Black of Flanders’ to fade over the following centuries. But for Mayerne, a welcome guest at royal courts on both sides of the Channel and an intimate to many a member of Europe’s nobility, the luxurious black cloth for which Flanders became famous in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries must still have vividly resonated with his own colour world. The legacy of Burgundy’s black splendors has been immortalized by Flemish master painters like Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) who, as with many other artists, shared with Mayerne a knowledge of rendering sumptuous black fabrics in paint [Figures 8 and 9].[11]

The extraordinary quality of black broadcloth produced in the Flemish centers of the textile industry must have been seductively luxurious to the period eye and hand. Today, however, it is difficult to imagine the splendors of Burgundian black, as hardly any textiles from this period have survived. Yet what still speaks to our imagination are the splendid colours and sumptuous textures of black-dressed nobility and urban patriciates that survived by the hands of Flemish master painters, like the portrait of Philip the Good (c. 1445) by Rogier van de Weyden (1400-1464), and the double portrait of Antwerp’s most important English merchant and his wife, Sir Thomas Gresham (1519-1565) and Lady Anne Fernely (c.1520-1596), both painted in oil. The latter was painted between 1560 and 1565 by Anthonis Mor (c. 1519-1575), the son of a Dutch dyer, who gained fame at the Habsburg court as one of the most important portrait painters of his time and later court painter to Philipp II [Figures 10-12]. In their contribution to this collection, Erma Hermens and Suzan Meijer present some of the earliest surviving black textiles in Dutch collections and discuss the mastery of a remarkably broad range of black tones that textile artisans and Netherlandish portrait painters, like Mor and Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen (c. 1473/77-1528/33) [Figure 13], achieved when colouring black in fabric and paint. The role of manuscript illumination in propagating ducal self-presentations in black [Figure 4] and the art of black watercolouring is further discussed by Jenny Boulboulle and Birgit Reissland in their contributions on Burgundian miniature.

Back to Black

A substantial part of the research for this book focusses on historical making processes and the partly forgotten materials and techniques that were known to master dyers and colour makers in the premodern period. Initially, this project started as a collaboration between museum curators and historians of the European-funded ARTECHNE project to develop a research-driven exhibition for the new participatory space of the Belgian Museum Hof van Busleyden. The museum — located in a Renaissance palace in Mechelen, the former capital of the Burgundian Netherlands — tells the story of the Burgundian and early Habsburg Low Countries; it aims to do so, as the museum curators Samuel Mareel and Marijke Wienen explain, by ‘creating an active dialogue between past, present and future‘.[12] To bring this approach into practice, we invited textile artist Claudy Jongstra to join our collaborative efforts to explore and revive historic dye technologies. Jongstra and her team shared — from an artistic point of view — our fascination with Burgundian black. The historical research for the exhibition project, coordinated by Dr. Jenny Boulboullé, was conducted together with Natalia Ortega-Saez, researcher and textile conservator of the Heritage Department of the University of Antwerp, and Art Gaibor Proaño, organic colour specialist of the Cultural Heritage Agency Research Laboratory. All partners have contributed to this book (see the visual contribution by Claudy Jongstra and the essays by Natalia Ortega-Saez & Vincent Cattersel, and Art Gaibor Proaño & Chrystel Brandenburgh). The collaborative and interdisciplinary research resulted in the exhibition ‘Back to Black’, which ran in Mechelen from June 2019 to Summer 2021 and featured new work by Jongstra; this exhibition is the subject of Mareel’s and Wienen’s contribution to this collection [Figures 14 and 15].

The city of Mechelen — famous for its high-quality finished cloth — gained importance as a center of the luxurious textile industry in the Burgundian Low Countries and attracted royal patronage. Margaret of Austria (1480-1530), put in charge of the Spanish Netherlands by her nephew Charles at the beginning of the sixteenth century (1507-1515 and 1519-1530), moved her court to Mechelen, making the city the most important center of royal and mercantile powers and a hub for artisanal activity of remarkable quality and scale. The luxury quality woolens purchased for Mechelen’s burgomasters and aldermen in the first half of the sixteenth century aligned the chromatic politics of the town government with the aristocratic and clerical powers of the Burgundian Netherlands. The city’s town records document for this period a striking chromatic shift towards uniformly dark black dyed textiles that accounted for virtually the entire bulk of the town government’s commission. Burgundy’s chromatic politics was principally a dark-coloured affair: the ruling class, those who strove to share in the power of the rising urban elites, and those who could afford it, dressed in black. However, culturally, technically, and materially, there could lie worlds between the black of a habit of a monk and the black of a courtly houppelande. And as Ann-Laure van Bruaene reminds us in her contribution to this book, the ‘somber splendors of black robes’, famously described a century ago by Johan Huizinga in his Autumntide of the Middle Ages,[13] unfolded on a mournful European stage — a world turned black amidst the turmoil of an ongoing religious war.

The historical, art-technological, and artistic research into black shades favored by Burgundian-Habsburg rulers to display their power and authority also inspired a joint fashion project between Claudy Jongstra and the Dutch designers Viktor & Rolf that resulted in the Haute Couture collection Spiritual Glamour, featuring several luxurious black felted wool coats dyed with plant dyes inspired by historical dye procedures that were also on view at Museum Hof van Busleyden during the exhibition Back to Black [Figures 16 and 17].[14]

After the disintegration of the Burgundian Netherlands at the end of the sixteenth century, Leiden became, in the seventeenth century, one of the most important textile centers of the Dutch Republic. The famous Laecken-Halle of Leiden, an inspection hall for woolen cloth where the quality of the world-famous Leiden cloth was assessed and certified, was built in the 1640s, at the same time that Mayerne collected the Flemish secret for black dyeing still known to Leiden’s master dyers. Today, the Museum Lakenhal is based in the monumental building of the former Cloth Hall. Leiden’s Cloth Hall provided an inspiring context for a solo exhibition of Jongstra’s textile art that reflects her ongoing research into the rich shades and tones of Burgundian black (30 October 2020 – 29 August 2021 at Museum de Lakenhal), placing her own work in a long tradition of Netherlandish mastery of and experimentation with black wool dyeing using natural colourants.[15] For a documentary account of Jongstra’s process, see ‘Behind the Scenes with Claudy Jongstra,’ by Marit Geluk.)

Black Matters

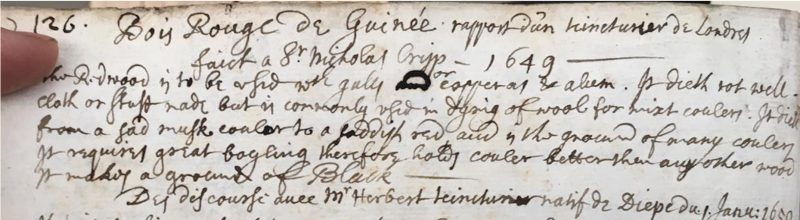

The close entanglement of the (global) trade in colouring matter with histories of human exploitation and the looming shadows of slavery became palpable during our research when we encountered another note of a London dyer among the Mayerne papers at the Royal Society Archives where we also found the recipe for Noir de Flandres. The latter note reports on dyeing with ‘redwood from Guinea done at Sir Nicholas Crisp 1649’, and praises the dyewood’s quality for black dyeing: ‘better than any other wood it makes a ground of black’.[16] As others have noted, Sir Nicholas Crisp (1598-1666) was a key figure in the West African trade in enslaved black people, who later became wealthy and was named a fellow of the Royal Society [Figure 18].[17]

Mastery of black colour technologies developed in the context of an ever-growing global (sea) trade in colourants (see the contribution by Jo Kirby in this book), and marks the beginnings of systematic exploitations of natural and human resources to serve the chromatic demands of western aristocracy and a rising new ruling class in the cities of Europe. The increasing availability of imported black and blue dyestuff of high quality, such as tannin-rich gall apples from Aleppo, and concentrated colourants extracted from indigo plants (Indigofera tinctoria L. and related species) native to India and Asia, likely contributed to the improved quality of black dyed textiles in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Throughout the centuries the import of dyestuff into Europe grew steadily, until the indigo trade from the Americas and the import of dyewoods — both used for black dyeing — expanded explosively in the seventeenth century.

https://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.616582

A double portrait of Marten Soolmans, the son of a wealthy owner of a sugar refinery, and his his wife, Oopjen Coppit. Her second husband was Maarten Daey, a captain of the West Indian Company engaged in the transatlantic slave trade.

While this book on Burgundian black does not deal with the histories of black people, it is important to note that black dyeing technologies grew increasingly intertwined with colonial affairs in the following centuries. Already in the late sixteenth century merchants from the Low Countries started to invest, for example, in the Atlantic sea trade in dyewoods.[18] European ships that transported enslaved people from western Africa travelled back via trading ports in e.g. Guinea, Angola, Brazil, and the Spanish West Indies with return cargo of gold, dyewoods and other commodities, thus linking the increasing import of colourants for Europe’s flourishing textile centers directly to the Atlantic slave trade.[19] In the seventeenth century, the beneficiaries of the trade and labour of enslaved people had themselves portrayed in sumptuous black cloth — reminiscent of the dark-coloured displays of power and wealth in the previous century [Figures 19 & 20; Figure 21].[20] The global history of fashionable and luxurious black dress abundant in Netherlandish early modern portraiture finds perhaps its beginnings in the dark splendors of Burgundian rulers.

While the focus of this book is elsewhere, we hope that it paves the way for more historical narratives that can tell us at what cost — in terms of human and natural resources — artistic mastery of black-coloured textiles had been achieved by the many hands involved in its production and trade. Hidden beneath the lustrous surfaces and velvety adornments of the stunningly beautiful black dress of Burgundian aristocracy and a rising urban patriciate lie dark stories yet to be told.

Colour Worlds

Colour research has been booming in the last decades. To navigate this expanding field, we can roughly divide the many publications into academic studies that testify to an increasing scholarly attention to colour matters, and popular trade books intended for a broad readership.[21] Not all publications fit easily into this division, though, such as, for example, the monochromatic series by the French cultural historian Michel Pastoureau, recently translated into English. Pastoureau devotes a volume to Black — Black: The History of a Colour — that provides a broader historical context and an important starting point for our own study.[22] Other historical studies have been published on specific colours and colourants,[23] as well as more wide-ranging edited volumes devoted to colour histories of broadly defined periods, such as Amy Buono’s and Sven Dupré’s Cultural History of Color in the Renaissance (2021), Tawrin Bakers et al.’s Early Modern Colour Worlds (2015), Andrea Feesers et al.’s Materiality of Colour (2012) focusing on the production, application, and circulation of pigments and dyes, 1400-1800, and Magdalena Bushart’s and Friedrich Steinle’s Colour Histories of the seventeenth and eighteenth century (2015). All of these works sharpen our awareness of chromatic complexities by examining a rich variety of past colour worlds and diverse bodies of colour knowledge.[24] In addition, relevant thematic studies and monographs appeared on the art and science of colours in manuscript illumination, on historic colour recipes and natural dyes and pigments, on textile dyeing from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period, and on stunning colour swatch books, that give us a palpable impression of lost textile colour worlds, dating however to a later period than considered in our book.[25] Moreover, this millennium saw the publication of much needed studies on the long history of trade in colour matter and traveling colour knowledge that firmly place Europe’s colour worlds in a global context.[26]

More specifically, we could draw on other works devoted solely to the colour black, including the catalogue Black: Masters of Black in Fashion & Costume, that accompanied the 2010 exhibition of the same name at the ModeMuseum Provincie Antwerpen, which presented black fashion from past to present, including several seventeenth-century black-dyed objects from Dutch and Belgian collections. The catalogue also features important historical contributions on the presence of black-dyed textiles in Antwerp households in the first half of the seventeenth century, and a chapter on historic black dye technologies by our partner Ortega Saez, whose dissertation on ‘Black Dyed Wool in North Western Europe, 1680-1850’ from 2018 provided a thorough foundation for our further research into black dye technologies from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; Jolivet, whose contribution to this book is based on an earlier French publication on the Duke of Burgundy and the colour black, provided with her dissertation (2003) a groundbreaking study of ducal financial records testifying to Philip the Good’s taste for black dress and revealing his chromatic politics.[27]

In this book, building upon this literature, we investigated how colour technologies and colour making knowledge can enrich our understanding of past colour worlds. Colour worlds are made; they are shaped by many hands and not simply given to the contemplator’s eye. How can we make sense of centuries-old colour knowledge, much of which was lost with the rise of synthetic colour industries from the nineteenth century onwards?

Recipe literature provides a rich source for the study of past colour worlds. We investigated the art of black colour making by reworking historic textile dye recipes and following instructions for pigment production and paint applications. While black dyeing is a complex and labour-intensive affair, as there exists no plant or mineral in nature that can directly and durably dye black, natural resources for black pigments were abundantly and cheaply available to painters and illuminators, though pigments sourced from rare and expensive raw material such as ivory where highly valued and used, too. As most of the contributions show, collaborative work has been key to study and revive the almost forgotten various ways to attain black shades with natural colourants that dyers and illuminators had access to. Some research questions that guided our collaborative efforts in understanding Burgundian black with reworkings of historic black colour making recipes included: Is it possible to decode the colour knowledge that artisans had at that time by performative methods? And how can we make sense of centuries-old colour knowledge, reworking historic recipes with modern means and methods? For example, Birgit Reissland’s study of illuminator’s colour technologies shows how much recipe reworkings can contribute to a better understanding of the chromatic mastery of Burgundian miniature painters. And Gaibor Proaño’s and Brandenburgh’s contribution on black dyed silk and wool stockings demonstrates how the process of remaking can serve as a fruitful starting point for generating historical questions concerning the production, and wear and tear of historic textiles.

In workshops with experts and students we experienced that Burgundian black was not only a visual but also a multi-sensory phenomenon (on our reworkings of dye recipes at different sites see also Boulboullé’s and Dupré’s essay in this book) [Figures 21 and 22; Videos Smelling, Hearing, and Touching].[28] The essays that we bring together here also show that we cannot conceptualize Burgundian black as a chromatic phenomenon that easily fits into our current disciplinary divisions and medium-specific categories. The colour black played a vital role in many domains in the Burgundian-Habsburg Netherlands. Jessie Wei-Hsuan Chen’s reconstruction of the biography of a blackened woodblock that was used in Antwerp’s most famous printshop reveals, for instance, a paper world in which artisanal and medicinal plant knowledge travelled in print. Only by studying chromatic expertise across a variety of artisanal media, including textile dyes, oil paints, watercolours, and woodblock printing, could we gain a deeper understanding of entangled knowledge domains, the political affordances of black and the socio-material environments that allowed for its production.

The collaboration with museum curators allowed us also to investigate if Burgundian black still speaks to the imagination of a contemporary public. The public participation research conducted in context of the ‘Back to Black’ exhibition was ongoing when this book was launched.

Smelling – Natalia Ortega-Saez and Art Gaibor Proaño assessing the quality of a fresh indigo dye vat at the Burgundian Black ROOHTS Summer School at the University of Antwerp, Antwerp 1-4 July 2019 @Artechne/Boulboullé

Hearing – Grinding black pigments made from charred grape vine branches until the screeching sound of particles abates, Burgundian Black ROOHTS Summer School at the University of Antwerp, Antwerp 1-4 July 2019 @Artechne/Boulboullé

Touching – Assessing the quality of cloth samples that were dyed following instructions from historical recipes, the Burgundian Black Collaboratory workshop at Claudy Jongstra’s farm in Friesland, The Netherlands, 18 January 2019, video clip @Artechne/Boulboullé

Huizinga was perhaps the first, and is likely the most famous and controversial historian, to use textual and visual sources to immerse his readers in a historical scene evoking a rich sensory experience of the Burgundian period.[29] Our approach in this project is to a certain extent indebted to Huizinga’s desire to immerse his readers in multi-sensory historical experiences. We explore in this book how hands-on recipe research — reworking historic ways of colour making that were known to premodern dyers and illuminators — can be put in the service of historical narratives that evoke multi-sensory experiences of the past and inspire today’s artists. Visual and filmic documentation of our recipe reworkings contribute in important ways to communicating some of the multi-sensory insights we gained from studying Burgundian black by performative methods.

Finally, the book features an addendum with which we hope to share our enthusiasm for historic black colour technologies in a hands-on way. Birgit Reissland has compiled an online handbook with historic recipes for making, studying and teaching black watercolour technologies, ‘Practical Guide for Black Pigments and Illumination, 1350-1700’. With this open access resource, we invite our readers to literally get their hands dirty and immerse themselves in the multi-sensory worlds of black colour making using domestic waste and easy-to-source raw materials, like peach pits and birch bark.

This book has been from beginning to end a collaborative work, we thank everyone who has contributed to its realization.

Bibliography

Baker, Tawrin, Sven Dupré, Sachiko Kusukawa, and Karin Leonhard, eds. Early Modern Color Worlds. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2015.

Balfour-Paul, Jenny. Indigo in the Arab World. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 1997.

Bomford, David, and Ashok Roy. Colour: A Closer Look. London : [New Haven]: National Gallery Co. ; Distributed by Yale University Press, 2009.

Boulboullé, Jenny. “Drawn up by a Learned Physician from the Mouths of Artisans: The Mayerne Manuscript Revisited.” Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art / Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek Online 68, no. 1 (August 5, 2019): 204–49. https://doi.org/10.1163/22145966-06801008.

Boulton, D’Arcy Jonathan Dacre, and Jan R Veenstra, eds. The Ideology of Burgundy: The Promotion of National Consciousness, 1364-1565. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2006.

Buono, Amy, and Sven Dupré, eds. A Cultural History of Color in the Renaissance. Vol. 6. 3 vols. A Cultural History of Color Series, Vol. 3, General Eds. Carole P. Biggam and Kirsten Wolf. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Bushart, Magdalena, and Friedrich Steinle, eds. Colour Histories: Science, Art, and Technology in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Berlin ; Boston: De Gruyter, 2015.

Cardon, Dominique. Des couleurs pour les Lumières: Antoine Janot, teinturier occitan : 1700-1778. Paris, CNRS Editions, 2019.

———. Le monde des teintures naturelles. Paris: Belin, 2014.

———. Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science. London: Archetype, 2007.

———, ed. The Dyer’s Handbook: Memoirs on Dyeing. Ancient Textiles Series, vol. 26. Oxford ; Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, 2016.

Chen, Jessie Wei-Hsuan. “Learning from a ‘Living Source’.” The Recipes Project (Edited by Joshua Schlachet) (blog). Accessed March 19, 2021. https://recipes.hypotheses.org/15500;

Chenciner, Robert. Madder Red : A History of Luxury and Trade. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2011.

De Mayerne, Sir Theodore, et al., et al., and et al. “Pictoria, Sculptoria, Tinctoria at Quae Sub- Alternarum Artium Spectantia; in Lingua Latina, Gallioa, Italiea, Germanica Con- Scripta a Petro Paulo Rubens, Van Dyke, Somers, Greenberry, Janson &c. Pol. No XIX.” Manuscript. London, 1655 1620. British Library.

De Nie, Willem Leendert Johannes. De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij van de 14e tot de 18e eeuw. Leiden: IJdo, 1937. https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMKB06:000008547.

Delamare, François, and Bernard Guineau. Colour: Making and Using Dyes and Pigments. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Den Heijer, H. “Een Afrikaan in Leids laken. De Nederlandse textielhandel in West-Afrika, 1600-1800.” In Alle streken van het kompas: maritieme geschiedenis in Nederland, edited by Maurits Alexander Ebben, H. J. den Heijer, J. C. A Schokkenbroek, and F. S Gaastra, 277–94. Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2010.

Elena Phipps. “Global Colors: Dyes and the Dye Trade.” In Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, edited by Amelia Peck and Amy Elizabeth Bogansky. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.

Engel, Alexander. Farben der Globalisierung: die Entstehung moderner Märkte für Farbstoffe 1500-1900. Reihe “Globalgeschichte” 5. Frankfurt/Main New York: Campus-Verlag, 2009.

Feeser, Andrea, Maureen Daly Goggin, and Beth Fowkes Tobin, eds. The Materiality of Color: The Production, Circulation, and Application of Dyes and Pigments, 1400-1800. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012.

Finlay, Victoria. Colour: Travels through the Paintbox. London: Sceptre, 2003.

Gray, Todd. The Exter Cloth Dispatch Book, 1763-65. Exeter: Devon and Cornwall Record Society, 2021.

Hohti Erichsen, Paula. “Exploring Historical Blacks: The Burgundian Black Collaboratory.” The Recipes Project (Edited by Joshua Schlachet) (blog). Accessed March 19, 2021. https://recipes.hypotheses.org/15479

Huizinga, Johan. Autumntide of the Middle Ages. Edited by Graeme Small and Anton van der Lem. Translated by Diane Webb. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2020.

———. Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen: studie over levens- en gedachtenvormen der veertiende en vijftiende eeuw in Frankrijk en de Nederlanden. Edited by Anton van der Lem. Leiden University Press, 2018.

Jolivet, Sophie. “‘Pour soi vêtir honnêtement à la cour de monseigneur le duc de Bourgogne’” Université de Bourgogne, 2003. https://journals.openedition.org/cem/984.

Joseph, Gilbert M. “British Loggers and Spanish Governors: The Logwood Trade and Its Settlements in the Yucatan Peninsula: Part I.” Carribean Studies 14, no. 2 (1974): 7–37.

Kastan, David Scott, and Stephen Farthing. On Color. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

Keller, Vera. “Scarlet Letters: Sir Theodore de Mayerne and the Early Stuart Color World in the Royal Society.” In Archival Afterlives: Life, Death, and Knowledge-Making in Early Modern British Scientific and Medical Archives, edited by Keller, Vera, Anna Marie Eleanor Roos, and Elizabeth Yale, 23:72–119. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2018.

Kirby, Jo, Van Bommel, Maarten, and Verhecken, André, eds. Natural Colorants for Dyeing and Lake Pigments : Practical Recipes and Their Historical Sources. London: Archetype Publications, 2014.

Klooster, Wim. “Het Begin van de Nederlandse slavenhandel in het Atlantisch gebied.” In Alle streken van het kompas: maritieme geschiedenis in Nederland, edited by Maurits Alexander Ebben, H. J. den Heijer, J. C. A Schokkenbroek, and F. S Gaastra, 249–62. Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2010.

Klooster, Wim. The Dutch Moment: War, Trade, and Settlement in the Seventeenth-Century Atlantic World, 2016.

Larminie, Vivienne. “Peter de Lannoy: A Southwark Huguenot in Parliament.” The Huguenot Society (blog), June 17, 2020. https://www.huguenotsociety.org.uk/blog/peter-de-lannoy-a-southwark-huguenot-in-parliament.

Lookman, Sharifa. “Experiencing Historical Techniques through the Color Black at the ROOHTS Summer School.” The Recipes Project (Edited by Joshua Schlachet) (blog). Accessed March 19, 2021. https://recipes.hypotheses.org/15543

Making and Knowing Project, Pamela H. Smith, Naomi Rosenkranz, Tianna Helena Uchacz, Tillmann Taape, Clément Godbarge, Sophie Pitman, et al. Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640. Digital Critical Edition. New York, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org.

Mandrij, V.E.. “Touching the Perfect ‘Noir de Flandres’: A Visitor’s Experience at the Museum Hof van Besleyden.” The Recipes Project (Edited by Laurence Totelin) (blog). Accessed March 19, 2021. https://recipes.hypotheses.org/15719.

Mayerne, Théodore Turquet de, and et al. “Classified Papers, Bois Rouge de Guinée.” Manuscript. London, 1649. Royal Society Archives.

———. “Classified Papers, Noir de Flandres.” Manuscript. London, 1646. Royal Society Archives.

Nance, Brian. “Turquet de Mayerne as Baroque Physician: The Art of Medical Portraiture.” Clio Medica 65. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2001.

Neven, Sylvie. The Strasbourg Manuscript: A Mediaeval Tradition of Artists’ Recipe Collections (1400-1570), London: Archetype Books, 2016. https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/194825.

Oostindie, Gert, Karwan Fatah-Black, Gert Oostindie, and Karwan Fatah-Black. Sporen van de Slavernij in Leiden. Leiden University Press (LUP), 2017. https://hdl.handle.net/1887/57676.

Pastoureau, Michel. Black: The History of a Color. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Ponte, Mark. “Unknown slavery stories behind famous Rembrandt paintings.” Voetnoot.org (blog). Accessed March 4, 2021. https://voetnoot.org/.

———.“Onbekende slavernijverhalen achter bekende Rembrandts.” Over de muur (blog), January 31, 2018. https://overdemuur.org/onbekende-slavernijverhalen-achter-bekende-rembrandts/.

Porter, R. “The Crispe Family and the African Trade in the Seventeenth Century.” The Journal of African History 9, no. 1 (January 1968): 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853700008355.

Quye, Anita, Dominique Cardon, and Jenny Balfour Paul. “The Crutchley Archive: Red Colours on Wool Fabrics from Master Dyers, London 1716–1744.” Textile History 0, no. 0 (September 14, 2020): 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00404969.2020.1799731.

Ribeiro da Silva, Filipa. “Crossing Empires: Portuguese, Sephardic, and Dutch Business Networks in the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1580-1674.” The Americas 68, no. 1 (2011): 7–32.

Ribeiro da Silva, Filipa. “Forms of Cooperation between Dutch-Flemish, Sephardim and Portuguese Private Merchants for the Western African Trade within the Formal Dutch and Iberian Atlantic Empires, 1590–1674.” Portuguese Studies 28, no. 2 (2012): 159–72. https://doi.org/10.5699/portstudies.28.2.0159.

Serrano, Ana. “The Red Road of the Iberian Expansion: Cochineal and the Global Dye Trade.” Centro de História d’Aquém e d’Além-Mar, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa e Universidade dos Açores, 2016.

Small, Graeme. “The Making of The Autumn of the Middle Ages I: Narrative Sources and Their Treatment in Huizinga’s Herfsttij.” In Rereading Huizinga, edited by Peter Arnade, Martha Howell, and Anton van der Lem. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvnwbznh.12.

Struckmeier, Sabine. Die Textilfärberei vom Spätmittelalter bis zur Frühen Neuzeit): eine naturwissenschaftlich-technische Analyse deutschsprachiger Quellen. Cottbuser Studien zur Geschichte von Technik, Arbeit und Umwelt 35. Münster: Waxmann, 2011.

Trevor-Roper, Hugh. Europe’s Physician: The Various Life of Sir Theodore de Mayerne. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2006.

Woudhuysen-Keller, Renate. Das Farbbüechlin Codex 431 aus dem Kloster Engelberg: ein Rezeptbuch über Farben zum Färben, Schreiben und Malen aus dem späten 16. Jahrhundert. 2 vols. Zürich: Abegg-Stiftung, 2012.

[1] Recipe for “Noir de Flandres”, manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34. First mentioned in Keller, “Scarlet Letters: Sir Theodore de Mayerne and the Early Stuart Color World in the Royal Society,” 118.

[2] M. de Lanoy has been identified as Pierre de Lanoy, a Walloon dyer in Southwark, Keller, “Scarlet Letters: Sir Theodore de Mayerne and the Early Stuart Color World in the Royal Society,” 118. Pierre/Peter de Lanoy is likely the later MP Peter de Lannoy (1607 – 1675), a Southwark Huguenot and dyer like his father and grandfather, who was elected into parliament in 1656, probably also an importer of colorants, Vivienne Larminie, “Peter de Lannoy: A Southwark Huguenot in Parliament,” The Huguenot Society (blog), June 17, 2020, https://www.huguenotsociety.org.uk/blog/peter-de-lannoy-a-southwark-huguenot-in-parliament, last accessed on 22 February 2021.

[3] On Theodore de Mayerne, see e.g., Trevor-Roper, Europe’s Physician: The Various Life of Sir Theodore de Mayerne; Boulboullé, “Drawn up by a Learned Physician from the Mouths of Artisans: The Mayerne Manuscript Revisited”; Nance, Turquet de Mayerne as Baroque Physician: The Art of Medical Portraiture.

[3] On Theodore de Mayerne, see e.g., Trevor-Roper, Europe’s Physician: The Various Life of Sir Theodore de Mayerne; Boulboullé, “Drawn up by a Learned Physician from the Mouths of Artisans: The Mayerne Manuscript Revisited”; Nance, Turquet de Mayerne as Baroque Physician: The Art of Medical Portraiture.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.

[5] “Vous aurez un noir parfaict & durable”, first page (recto) of the bifolio, recipe for “Noir de Flandres,” manuscript, London, Royal Society Archives, ClP/3i/34.