Black dyeing was a major business during the Burgundian-Habsburg period, when Flanders textile centers flourished in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Ghent, Bruges, Antwerp, Duffel, Hondschoote (now Northern France), and Nekkerspoel (Mechelen) were known centers of the textile industry.[1] During the sixteenth and the first half of the seventeenth century, Antwerp was the main center for processing (i.e. dyeing and finishing) fabrics, which were then shipped woven but unfinished along the river Scheldt. After the fall of Antwerp in 1585, the focal point shifted from Antwerp to northern Netherlandish cities such as Leiden and Amsterdam.[2] Black and dark coloured textiles characterized the courts’ fashion during the reign of the Dukes of Burgundy in the fifteenth century, and in the courts of Spanish Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) and his son Philip II (1527-1598) in the sixteenth century,[3] thus, influencing the wardrobe of Southern Netherlandish nobility. Promoted by the elite, black became an important colour-concept in these societies, especially for the textile producing and colouring industries.

The colour black related to a palette of different hues and shades including reddish, brownish, and greenish black. The different hues and shades depended on the material to be dyed, the dye’s recipe, and the dyeing procedure. Historical evidence from the fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries shows that different shades of black were available, and there was a rich vocabulary to refer to them. For instance, ‘taneet’ (a very dark brown), ‘kastoorzwart’, ‘bleckzwart’, ‘ zijdezwart’, ‘Greinzwart’ and ‘Fusteinzwart’, all denote the different types of black hues and shades.[4] The popularity of certain black shades was dependent on the prevailing fashion and taste of the period. The notions of jet or raven black that became popular in the nineteenth century, and are still in use today, were not yet commonly used to describe black-dyed fabrics during the Burgundian period.[5] However, Theodore de Mayerne mentions a ‘black like jet, very beautiful’. [6]

Video: Reworking a ‘lasagna’ recipe from the Venetian Plictho (1548) with Natalia Ortega Saez, Atelier Building Amsterdam. A film by Katrien Vanagt and Stefano Bertacchini, 2020 @Serafín Productions for ARTECHNE

Based on diverse historical sources, it can be assumed that almost half of all dyed textile in the Netherlands during the sixteenth century was dyed black.[7] Given the importance of the black colour varieties available in the Burgundian-Habsburg Netherlands, we wanted to gain a better understanding of historic black dyeing technology. For this study we employed a multifaceted approach with a multidisciplinary research team. The study of black historical textiles is complex due to the many techniques available to make different types of textile, the intricate nature of different textile fibers, the various dyeing technologies to produce different blacks, and the numerous ingredients needed to obtain black. What fascinated us is how black was dyed, since there is no single colourant in nature that is capable of dyeing textiles black by itself. Consequently, dyeing black involved various dyeing substances and procedures resulting in one of the most complex, labour intensive, and expensive production processes for colouring textiles.

First, we had to take into account the various dyeing procedures that depended on the material to be dyed, guild regulations, and the period. Wool, for example, was more strictly regulated than silk in the period. And dyeing could be applied at different production stages [Figure 1 a-b]. For instance, the textile could be dyed directly in the fleece (this was appropriate for wool), but also after spinning or after weaving. Moreover, it was possible to dye the yarn or the unspun fibers, then weave it and re-dye the woven item. This last method, which gave a very deep black colour, was only used for the most expensive fabrics.

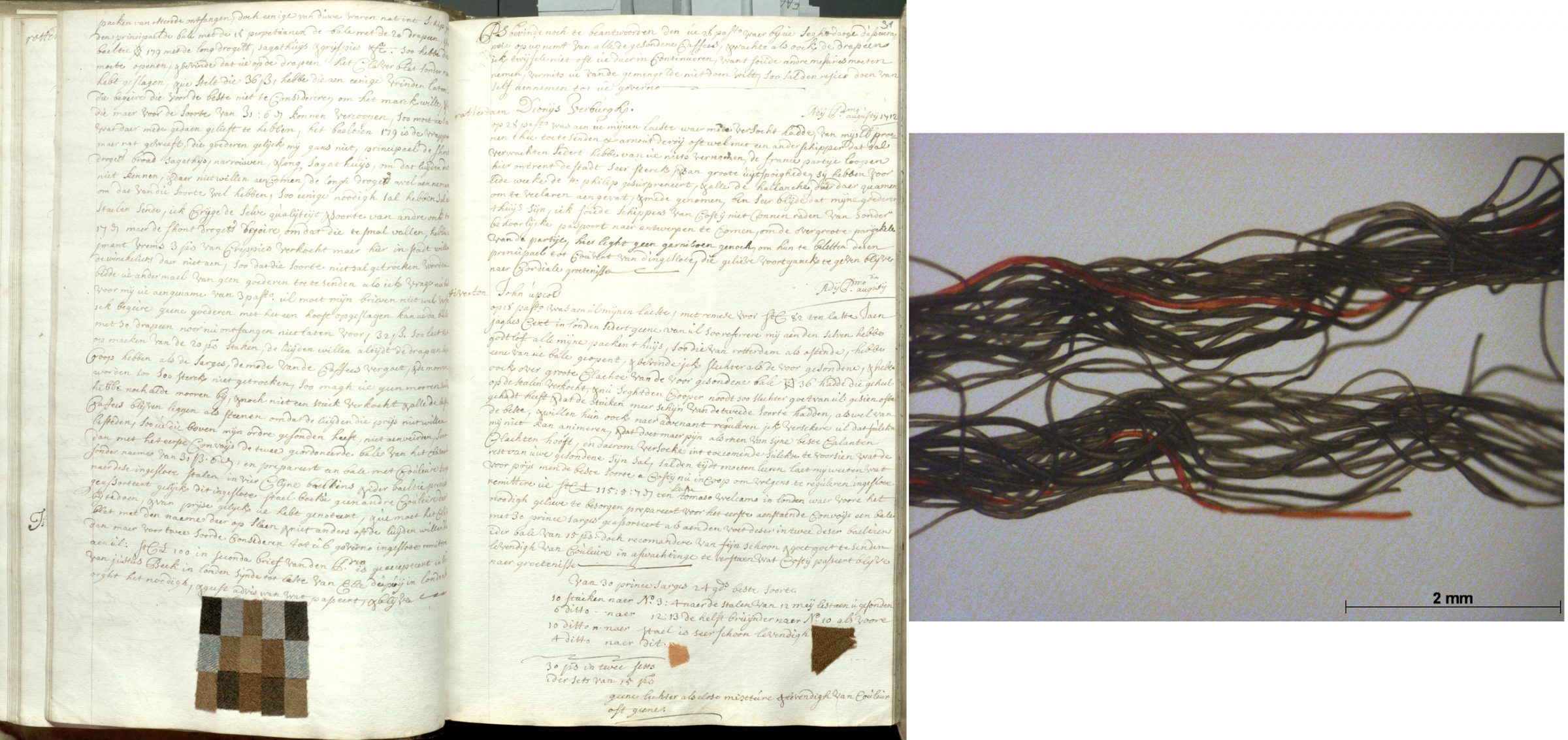

Microscopic examination shows that the black yarns were composed of a majority of black fibers, spun together with a small number of red-dyed fibers. This is the case for sample W26 from the Melijn Archive[8] found in book T94/189, fol.30, v.1712 and sample W29 of the same book fol.158, v.1714.[9]

Water was a crucially important raw material, not only needed for washing but also for dyeing and rinsing the dyed textiles. Before dyeing the fibers were washed, to remove its natural greasy coating allowing the dyeing material to adhere homogenously to the fiber.

In Antwerp, Amsterdam and Leiden the water was mainly taken from the canals that ran through the city. The water hardness and possible contamination was decisive for dyeing quality and the outcome of the colour. For example, various recipes refer to the addition of bran because it softens the water.[10] Using soft water was crucial to dye red colours (madder and cochineal) since hard water would sadden the colour. Also, in many cities such as Delft and Amsterdam dyers of different colours were separated because their waste water would contaminate the water of other dyers and therefore have negative consequences on their products’ quality. The dyers for dark colours were separated from the ones with lighter colours. Regulations ordered the dyers not to run their waste water back into the canals. A practical problem which has also been observed in Antwerp. In the city of Antwerp dyers rinsed their fabrics in the Scheldt in so called ‘rinse boats’ and on scaffolds specially constructed for rinsing fabrics. A dispute dating from 1625 was found in the Antwerp archives, involving a ‘kleurverver’ (a ‘colour dyer’) who claimed that it was impossible to work between his two neighbors, who were black dyers, and discharged their dye kettles in the river Scheldt, as a result of which the water turned black.[11] According to De Nie dyer’s in the Netherlands had the possibility to use four sources of water. First they could use the water from the many canals and watercourses within the city. Second, the dyers could collect rainwater in barrels and cisterns. Third, they could dig wells, and, fourth, they could import water from outside the city. We can assume that dyers preferred to use water from streams or canals due to the large quantities that were needed for dyeing. Quantities that could not be provided by collecting rainwater or groundwater.[12]

This article focuses on the re-working and the observation of a selection of historical recipes for dyeing textiles black from the Burgundian and early modern period. It discusses the procedures and results of the experiences gathered from collaborative workshops and a summer school.

A multifaceted and collaborative approach

The recipes were selected from a corpus of black dyeing recipes collected by Suzanne Bul, a research masters student of technical art history from the University of Amsterdam, UvA under supervision of Jenny Boulboullé. In November 2018 a number of historical black dye recipes were reworked by Natalia Ortega Saez together with Bul and Boulboullé during a trial-run at the University of Antwerp. This trial-run was a preparation for a three day expert workshop planned for the following year [Figure 2].[13]

In January 2019 Boulboullé and the textile artist Claudy Jongstra co-organized, together with Ortega Saez and Art Gaibor Proaño (The Cultural Heritage Agency Research Laboratory of the Netherlands, RCE) a three-day historical dyeing workshop in Húns in Friesland, co-funded by the Museum Hof van Busleyden. During this Burgundian Black Collaboratory, an international team of dyeing, colour-technology, and textile experts were hosted by Studio Claudy Jongstra and Farm of the World (now Extended Ground) in Húns to rework the colour black with a selection of historical black dyeing recipes on site at the artists’ farm.[14] The workshop conducted practical research for the exhibition project Back to Black in the Museum Hof van Busleyden in Mechelen and the Antwerp Summer University ROOHTS on Burgundian Black that took place in July 2019 [Figure 3].[15]

Similar to the workshop at Studio Claudy Jongstra, the ROOHTS Summer University focused on the re-creation of historical recipes for black dyeing but also incorporated other colour making recipe types, such as the study and re-creation of black writing inks and pigments [Figure 4].[16]

Video: Results from reworkings of historic recipes for writing inks, pigments and black dyed textiles during the Summer University ROOHTS, Burgundian Black (2019), University of Antwerp, © N. Ortega Saez.

The result was an intensive five-day program filled with theoretical and laboratory seminars [Figures 5 and 6]. For recipes executed in the laboratory at the University of Antwerp during the ROOHTS Summer University, the availability of scientific equipment, such as precision scales, modern heating equipment, pH meters, and thermometers stood in stark contrast to the artisan’s tools and workshop setting of pre-modern times, which we attempted to approximate in Húns. Such modern equipment improved the success rate of the reconstruction and provided proper safety measures for its execution.

Video: Some reflections and experiences of the organisers and participants of the summer school ROOHTS, Burgundian Black (2019), University of Antwerp.

There are many different recipes to produce the colour black from Burgundian times, and they require various methods to produce. As mentioned earlier, black dyed textiles were highly valued at the Burgundian ducal courts, whereas black inks and pigments were essential for depicting these black textiles in contemporary manuscripts and paintings.

A multidisciplinary team of conservation scientists, art historians, and technical art historians guided the participants throughout the course of reading and interpreting historical recipes, and performing the reconstructions. For the ROOHTS Summer University, the University of Antwerp again joined forces with the ERC-granted ARTECHNE research group from the Utrecht University, the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (RCE), the University of Amsterdam, and the Museum Hof Van Busleyden in Mechelen.[17] The selected recipes mentioned later in this article were reproduced several times by various people with different backgrounds, such as artists, art historians, and conservators, in order to unravel the dyeing practices and the feasibility of the recipes[18] [Figure 7].

This collaborative method helped us to understand the process of making and also helped us to work through fragmentary source materials and reimagine lost techniques; by reconstructing these historical recipes, we unravelled the meaning of technique and materiality.

The ROOHTS Summer University encouraged discussion and reflection in and between groups and also allowed participants to experience and relive aspects of the workshop in early modern times. This aspect is beautifully captured by the blog writings of one participant, Sharifa Lookman: ‘[W]hen all thirteen of the participants and a handful of instructors were in the lab together, we more or less simulated an active ‘workshop,’ complete with masters and apprentices, back-and-forth shop talk, and bustling bodies’.[19] This workshop environment ultimately allowed for collaboration and surprising variety, as different groups following the same recipes would produce significantly different results.

This variety raised questions regarding the historical difficulties of mastering production processes in such a manner that differences between different production batches were minimized. Additionally, the variety of shades confronted us with the current limitations of our language and our oversimplified perception of the colour ‘black’. It showed that in the modern Dutch and English there is little vocabulary in use for describing the variation of black colours. For instance, ‘light-black’ is never used, instead ‘dark-grey’ is a more common description. By contrast, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries southern and northern Netherlandish artisans used a broad vocabulary to designate different shades of blacks, as we have seen above[20] [Figure 8].

Reconstructing historical recipes — or, more appropriately, ‘reworking’ these recipes — reveals the limits of extant historical technical information, not least because reworking historical recipes requires actions that are not described in the historical texts.[21] Hence, reworking allows today’s scholars to close in on the historical artisans’ bodily experiences during the process of making through direct physical interaction with materials, tools, products, and chemicals used by dyers of previous generations.[22]

The interpretation of the written recipes relied on the scholar’s knowledge of historical techniques and the ingredients’ properties and names. While attempting to find modern versions of materials mentioned in recipes, we relied on academic research, and we found that the translation of written procedures into practice relied on trial and error as we reworked the recipes and production procedures. Reworking the recipes also required rethinking and refocussing our habitual daily actions because many of the actions performed during these reworkings mirror those in our daily lives. For example, actions needed for cooking using yeast and fermenting agents (bread making, beer brewing), or like dissolving, mixing or boiling substances, or those performed while doing laundry, such as submerging and washing-out textiles or hanging clothes to dry. These are all activities that we are well accustomed to in our daily lives, therefore, we are so familiarized with them that we rarely raise questions as to how and why we are performing them. Asking these questions was our goal. Early modern artisans’ relied on their senses for the characterization of their ingredients and mixtures, and we did as well. Raising awareness of and curiosity about these actions by focusing on the sensory engagement with the materials and production procedures was key to ‘reliving’ the artisans’ experience of the making process. The combined use of senses is a necessity to experience and absorb the large amount of information while performing the reworking of historical recipes.

A beautiful example is the sensory awareness aroused during the indigo/woad bath (a recipe from Tbouck va[n] Wondre 1513, Brussel Vander Noot), where at a certain point, the bath releases smelly vapors, indicating that the alkalinity of the bath has reached the correct point (this is illustrated later in this chapter).

Reworking Historical Dye Techniques Using a Selection of Historical Recipes

Understanding the technology of dyeing requires a combination of a chemistry and practical experience with historical materials. We can assume that in the Burgundian Habsburg period there were three ways to obtain the black colour.[23] These three ways were identified by analyzing the presence and absence of certain ingredients in historical recipes from Burgundian-Habsburg Netherlands up to the seventeenth century.[24]

The first method consists of a two-stage dyeing process. A blue undertone is obtained by vat dyeing with woad (Isatis tinctoria L.) and/or indigo (Indigofera tinctoria L.). Next, the blue-dyed textile is top dyed with a red mordant dye, most commonly madder (Rubia tinctoria L.), resulting in a black with a purplish hue. This manner of dyeing was prescribed by the guilds from as early as the Middle Ages until the end of the seventeenth century [Figure 9]. A second dye method called Schorston (‘alder bark liquor vat’) consists of combining tannins and metal salts and oxides. The final method combines methods one and two, a dark blue undertone dyed with woad and/or indigo, and it could also be used in combination with logwood (Haematoxylum campechianum L.), tannins, and iron salt added to the dyebath. This method became popular at the end of the seventeenth century, whereas a variation of this method was used at the start of the seventeenth century.[25] These methods are discussed briefly later in this chapter.[26] As we can see in the below comparison, these methods produce very different results:

Mordant dye

Most natural dyes are mordant dyes, nowadays known as ‘metal complex dyestuffs’. The chemical principle of this group is the bonding of the metal salt to the organic dyestuff molecule. This occurs by forming an insoluble metal complex. The dye is chemically and physically bound to the fiber (by means of ‘Van der Waals’ forces). The chemical bonding is easier with wool and silk (protein) than with cotton and linen (cellulose). The most common mordants used in history to dye were iron and alum. Alum is the most common metal found in the earth’s crust (8.3% by weight) followed by iron (6.2%).[27]An important red mordant dye used for black dyeing is madder (Rubia tinctoria L.) obtained from the roots of species belonging to the Rubiaceae family.

Vat dye

Woad (Isatis tinctoria L.) and later indigo (Indigofera tinctoria L.)[28], both blue dyes with indigotin as a dye component, are commonly known as vat colours. After harvesting the green leaves from the plants, they are crushed into pulp in mills. The crushed leaves are then kneaded into balls and dried in drying ranges or racks. These drying ranges are well-ventilated wooden erections supporting a series of gratins. This process takes from one to four weeks. When thoroughly dried, the balls are taken to the store rooms. In the couching house the final preparation of the dye takes place. The woad balls are ground into powder and the pulverized mass is piled up into a layer of two or three feet deep. This mass is then sprinkled with water and left to ferment (decompose) for about nine weeks. The fermenting mass is turned over frequently and sprinkled with water until it has converted into a paste (this process emits disgusting odors). After this process, the paste is dried and ready to trade.[29], [30]The organic colouring substances extracted from the plants are insoluble in water but by inducing alkaline reduction during dyeing — using potash (obtained from wood ashes) in combination with madder and bran to accelerate the fermentation process — they form a leuco-colour, which then becomes water soluble. This is the colourless water-soluble form of indigo. The fabric is immersed in this colourless solution. The molecules attach themselves with the fibers by van der Waals forces and some dipole bonds. After exposing the fabric to the air, oxidation occurs and the colour appears on the fibers. This action can be repeated several times. By repeating the above process, the blue colour of the textile will gradually get darker.[31]

The First Method: A Dark Blue Undertone Top-Dyed with Red

This labour- and time- intensive two-stage dyeing process corresponds to the first method where one layers red plant dyes on top of a dark woad/indigo blue undertone. This was one of the most elaborate and expensive methods by which to dye black and it involved two different artisanal specializations.[32]

First, the blue undertone was dyed by ‘De blauwers’ (the blue-dyers). These woad/indigo dyers were considered the elite of the profession and normally specialized in this one dyestuff. The process was the most complex of all dyeing processes as it involved controlled fermentation.[33] The woad or indigo was stored in wooden or copper vats which were maintained for several days at 40-50°C to induce and promote fermentation; maintaining this temperature outside the laboratory requires specific technical knowledge. [34]

According to Willem L.J. De Nie, the woad vat remained popular until the end of the sixteenth century. From then onwards the indigo vat was used and woad was added as a fermenting agent. Dyers were obliged to first dye the textile into a very dark blue by dipping the cloth several times into an indigo vat. This deeply dyed dark-blue textile would serve as an undertone and was then treated with alum and tartar to fix the dye and enhance its wash-fastness and lightfastness.[35] Next, the fabric was rinsed and dried, inspected by the guild’s authorities and sent to the ‘roodzieders’ or red dyers.[36] The blue undertone was top-dyed with madder and an alum mordant. This manner of working was prescribed by the dyers’ guilds from as early as the Middle Ages until the end of the seventeenth century.[37]

According to the guild’s authorities in Leiden, all cloth that had to be dyed black had to be dyed blue with woad first (1333-1480).[38] Additionally, a solid dark blue undertone was required for dyeing black [Figure 10]. Likewise, in sixteenth-century Antwerp, archival evidence from 1521 points to the process of using woad, and later indigo, as a required blue undertone for dyeing black.[39] These dyers eventually developed other procedures to obtain the darkest and deepest black, or as mentioned in a later period by Wiliam Patridge, jet or raven black.[40]

As seen in Figure 11, ‘staalmeesters’ or syndics of the cloth hall of Leiden checked the blue undertone against a swatch of official samples. When the blue undertone was considered dark enough, the woolen cloth was stamped or sealed with a lead seal to signify that it had been inspected and met the guild’s standards. This seal covered and protected a small part of the woolen cloth during the red dye bath. In this way, the blue undertone was protected from the red dyeing process and could still be checked after the removal of the seal. Checking the blue undertone served as a quality guarantee, provinding the potential buyer with an assurance that the fabric was dyed according to the guild’s standards for dyeing a high-quality black.[41] This two-stage process of dyeing resulted in a black of a reddish hue. Antwerpians of the sixteenth century called this type of black ‘meekrap zwart’ (‘madder black’).[42]

The complexity of setting a woad vat is illustrated by a recipe from Tbouck va[n] wondre (The Book of Wonders), a so-called ‘book of secrets’ from the southern Netherlands. This work was first published in Brussels in 1513 by Vander Noot. Later, in 1544, Simon Cock reprinted it in Antwerp.[43] The recipe for blue dyeing here shows that the Medieval woad vat contained a mixture of potash, madder, bran, woad, and indigo. The recipe ‘om linen doeck schoō blaeu te doē verwen’ (‘to beautifully dye a linen cloth blue’) from Tbouck va[n] wondre, is a rare example of an extant recipe that reflects and explains the laborious process of dyeing blue. It is the first known printed book containing recipes for dyeing.[44] According to Brunello, it can be assumed that the Tbouck va[n] Wondre was not meant for professional dyers but for those interested in learning methods for dyeing.[45]

There are many ways of creating a blue vat, but some of the general rules for attaining a good vat are explained well in the recipe from Tbouck va[n] Wondre.[46] As mentioned above, the fermentation process before dyeing was complex but crucial. This fermentation takes place in an alkaline environment at a temperature between 40°C and 60°C. To produce this environment, the vat is set with rye bran and madder as reducing agents and potash as alkali. The recipe mentions stirring the solution to obtain ‘schuym van der bloemē’ (flower of woad), which is the scum that floats on the surface of the woad vat, the sign that the dye bath is ready to use, as shown in Figure 12, a reconstruction of an indigo woad vat.

Video: Jongstra works a woad vat according to the recipe in Tbouck va[n] Wondre.

Video: Annette Houben, master dyer at Studio Claudy Jongstra, works a woad-indigo vat according to a recipe from Tbouck va[n] wondre, expert workshop in 2019

The recipe also mentioned the leuko indigo when the solution turns greenish (al groene begint te werdë) and how important it is to let the bath rest for a while in order to be able to dye again. The scum or flower of woad is also used to make pigments especially for the illumination of missals.[47] The knowledge about the correct pH of the bath, determining the right fermentation temperature, and the shift of colour towards the green was all gained from the practical experience when reworking these historical recipes with master dyers.[48]

After dyeing this blue undertone, the fabric was sent to the red dyers ‘roodzieders’ to be dyed red with madder. [49]

The Second Method: Combining Tannins and Metal Salts:

Tannins have been used since prehistoric times for dyeing. Tannins are of vegetable origin and are common in the plant world, giving a greenish or bluish-black hue in combination with metal salts. Gallnuts (e.g. Aleppo or oak), bark (e.g. alder or oak), and leaves (e.g. sumac) were, for example, used to dye black. They are hydrolysable polyphenols: gallotannins and ellagitannins which are glucose esters of phenolic acids such as gallic acid and ellagic acid and were the preferred tannin type for black dyers, because in combination with iron ions they form blue-black coloured iron (II) tannate dye complex.[50]

To produce black dyes, tannins must be combined with metal salts, or — in this case — an iron compound. Iron swarf, rusty old nails, filings and dust from the grinding of edge tools in acetic acid, are easy and cheap to produce and are known as iron acetate.

Copper red, copperas (‘koperrood’ in Dutch or iron(II)sulphate) were common ingredients for dyeing black or for ‘saddening’ (i.e. nuancing a colour’s hue or vibrancy to attain duller and/or darker shades).[51] Iron sulphate is called copperas or green vitriol in English, ‘kupferwasser’ (copper-water) or ‘Eisenvitriol’ in German and ‘couperose verte’ in French. Ferrous sulphate (Fe.SO4.7H2O) is formed naturally by the oxidation of white iron pyrites (iron disulphide (FeS2) or marcasite by weathering. Copper sulphate, blue vitriol or blue copperas (CuSO4.5H2O) is a common by-product of the ancient methods of producing ferrous sulphate from pyrites.[52]

Alder Bark Liquor Vat (Schorston)

To attain a deep black shade with this recipe that calls for tannins and metal salts, we combined iron sulfate or iron swarf, iron filings, and rusty old nails with plant tannins from alder bark (Alnus glutinosa L.), sumac (Rhus coriaria L.), and walnut husks (Juglans regia L.) and gallnuts, making what was known as a Schorston, or Alder bark liquor vat. This was a very popular and far less complex manner of dyeing textiles black, common among early modern dyers. Examples of recipes in vernacular sources are found in Dutch in Tbouck va[n] Wondre (1513), in Italian in the Plictho de Larte (1548), and in German in Das Farbbuechlein (ca.1550-1600). The recipe follows a simple principle according to which a cask is filled with bark and water that stands five to six weeks, or longer; after this first standing or during this standing (depending on the recipe), an iron component is added. The iron can come from either an iron oxide, swarf, filings, or old iron, or from a combination of several iron components [Figure 13].

Setting up an alder bark vat did not require extensive practical experience, nor did it require us to establish and manage a fermentation process. While the alder bark vat method was commonly prohibited for wool dyeing in the Burgundian-Habsburg Netherlands, as evidenced by surviving guild regulations, it was allowed and widely practised for dyeing silk and mixtures of wool and silk.[53] The ingredients were combined in a vat (ton in Dutch), hence the referral to ‘vat’ in the name ‘alder bark vat’. Since this method requires combining a large variety of raw materials, the ratios between the materials are paramount for successful dyeing. For example, using too much iron sulfate could attack the textile fibers’ integrity and might ruin the wool.[54] From historical sources we can infer that alder bark vats were set in wooden barrels in which the dyers prepared the ‘alder bark liquor’ by combining layers of bark chips and iron.[55] Recipes for making alder bark vat dyes often include a preparatory section in which the process for making alder bark liquor is mentioned.

Distinct from the exotic and expensive indigo, the ingredients for the alder bark vat dyeing method could all be sourced locally and were easily accessible. This accessibility, when combined with the simplicity of this method of dyeing, means we might assume that it was widely performed in domestic contexts. While a generally easier method, however, the process was still time consuming because the whole content of the cask had to stand for more than a month before being used in dyeing. Conveniently, when a dyer used a part of the cask for dyeing, one could refill the cask with water and let it stand for another while. These ‘liquors’ could sometimes be used for over a year, and the liquor becomes more potent by age and reuse. Plictho de l’arte describes the process clearly, and was a visionary work for its time, being one of the first dyer’s manuals of its kind that has survived in print, conveying the artisanal know-how of a craft tradition that was still dominated by secrecy and oral transmission.[56]

Gioanventura Rosetti, the Plictho‘s author, apparently intended to break with this dominant tradition of craft secrecy:

Some eminent readers will note that the present work seeks the order that will be of benefit to those who wish to embrace it, and which will be so useful and profitable to those who will be dedicated to rightful gain. You must know that this is a work of charity that I bequeath for the public benefit, and which has been imprisoned for a great number of years in the tyrannical hands of those who kept it hidden and thus subject to Evangelic indignation, wherein it is written that nothing shall remain hidden that has once been revealed, nor concealed so that it is not evident. Wherein sweetest Readers I cajole you not to be subject to apostolic censure by dulling the virtue that the glorious GOD has wanted that men be endowed with, and for their comfort you can prosper and use it for the benefit of everyone.[57]

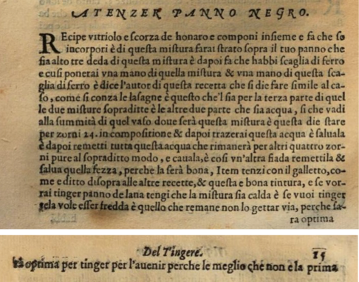

The Plictho gives us an unprecedented, detailed insight into dyers’ knowledge of the time.[58] The recipe ‘A tenzer panno negro’ is also quoted in Tbouck va[n] Wondre, testifying to the popularity and wide circulation of Plictho editions in early modern Europe. As discussed elsewhere,[59] it is remarkable that the prescribed method in guild regulations of this time, the two-stage blue-red dyeing, is not documented in this treatise.

The recipe of the Plictho gives instructions for making a ‘lasagna‘ of layers of alderbark, iron swarf, iron sulphate, and water in a vat — specifically, a large wooden barrel — that should stand for at least 24 days [Figure 14a]. After this, the liquor is used in combination with galls to dye black. When reconstructing this dyeing process in the laboratories at the University of Antwerp and in the Atelier Building in Amsterdam, we used a glass vessel in order to be able to observe the different layers of scale of iron and bark of alder, instead of a wooden barrel [Figure 14b see video above Reworking a ‘lasagna’ recipe from the Venetian Plictho (1548)].

A tenzer panno negro, a recipe reproduced from the Plictho [61]

‘To dye woolen cloth black’

Measure vitriol and bark of alder and mix together and that they are blended. Of this mixture you will make a layer on your ‘special’ cloth that be three fingers thick of this mixture. Then have a scale of iron and thus you will place one layer of that mixture and one layer of this iron scale. And, says the author of this recipe, one must do so as in the case when one prepares lasagna, so there be one third of those two mixtures above mentioned and the other two parts be water, so that it goes to the summit of the vessel where will be the mixture and this must stay for 24 days in composition. Then draw off this water and save it and replace all this water which then will remain for another four days also in the cited manner. Remove it, and so in another cycle, replace it and save those dregs, because they will be good. Then dye with the gall, as is said above in the other recipes. And this is good dyeing, and if you want to dye woolen cloth, dye so that the mixture is hot. If you want to dye linens it should be cold. What remains do not throw away because it will be excellent to dye in the future because it is better than the first.

Another Way to Dye Black

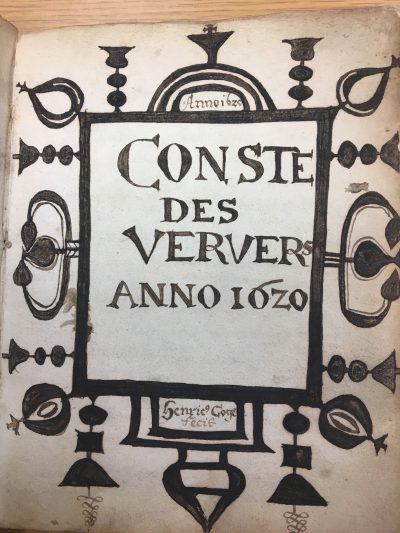

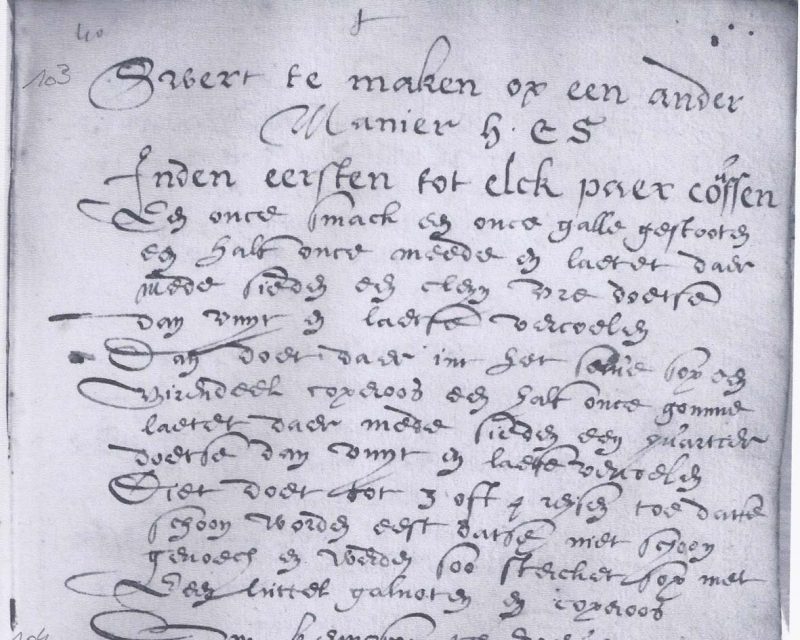

We found other historical recipes that also use tannins and iron; similar to the previous tannin-and-iron alder liquor vat recipe, the actual dye procedure is very quick and efficient, We called this other tannin-iron technology the ‘instant black method’, because it dyes the fabric immediately in a tannin-iron dye bath in contrast to the alder bark liquor vat, which requires a time-intensive preparatory fermenting phase that can take weeks or months before the liquid is ready for black dyeing. In these recipes there is no preparation section, and the ingredients are introduced directly into the dye bath. Found in Conste des ververs, students and scholars re-worked the recipe ‘Swert te maken op een ander manier’ (‘To make black in another manner’) several times. Similar ingredients were used in other slightly later vernacular recipe compilations and printed booklets.[62]

Conste des ververs (The Art of Dyeing), is a Flemish dyeing manuscript from Leuven, dated 1619-1623 written by Henricus Coghen Disthensis, a dyer from Diest who worked in Leuven (Brabant, Belgium). It is a largely unstudied manuscript of dyeing recipes kept in the archives of Leuven[63] [Figure 15]. The manuscript contains 121 recipes for dyeing wool, silk, linen, and feathers in different colours. 24 recipes were transcribed almost a century ago by Maurice Dieu, whose work on this valuable source, we believe, needs to be continued.[64] The rest of the manuscript remains unpublished. More recently, André Verhecken published a summary of the ingredients that appear in the book and offered a robust description of this exceptional manuscript. Very likely many of the recipes are based on the writer’s own experience in the dyehouse where he worked, and it is quite informal, often forgetting to name the textiles for which a given dyeing process would be most useful.[65] While most of the recipes use stockings, these stockings could be knitted of wool, linen, silk, or a combination of wool and silk. As with many historical recipes, this recipe is quite detailed but leaves room for interpretation [Figure 16].[66] The original recipe in English reads,

‘First for each pair of stockings one ounce Sumak one ounce galls crushed pounded half an ounce madder and let it seethe with it a small hour do that. Then wring and let it cool[.] Then put into the fresh dyebath a Quarter Iron II Sulphate half an ounce gum[.] Let it seethe with it a quarter [of an hour] do that then wring and let it cool[.] This you do up to 3 or 4 times so that they will be beautiful if they do not become beautiful Enough and so make the bath stronger with A bit of gall nut and Iron II Sulphate’. We translated the recipe into the following working protocol: ‘Leave sumac madder and gallnuts soaking and dye the material in this bath at 80°C. Take the material out of this bath. Ad Arabic gum, [and] iron II sulfate to the sumac madder gallnut bath and after this add the material for a second dye bath.’

Following this protocol, the fabrics were dyed several times in this bath at approximately 80 to 100°C, and the Arabic gum in this context served to give the textile a lustre; textile studies also suggest that gum Arabic was added to the dye bath to keep the tannins from galls in suspension.

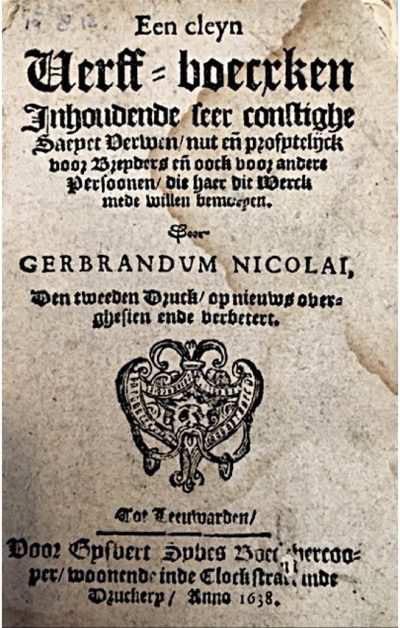

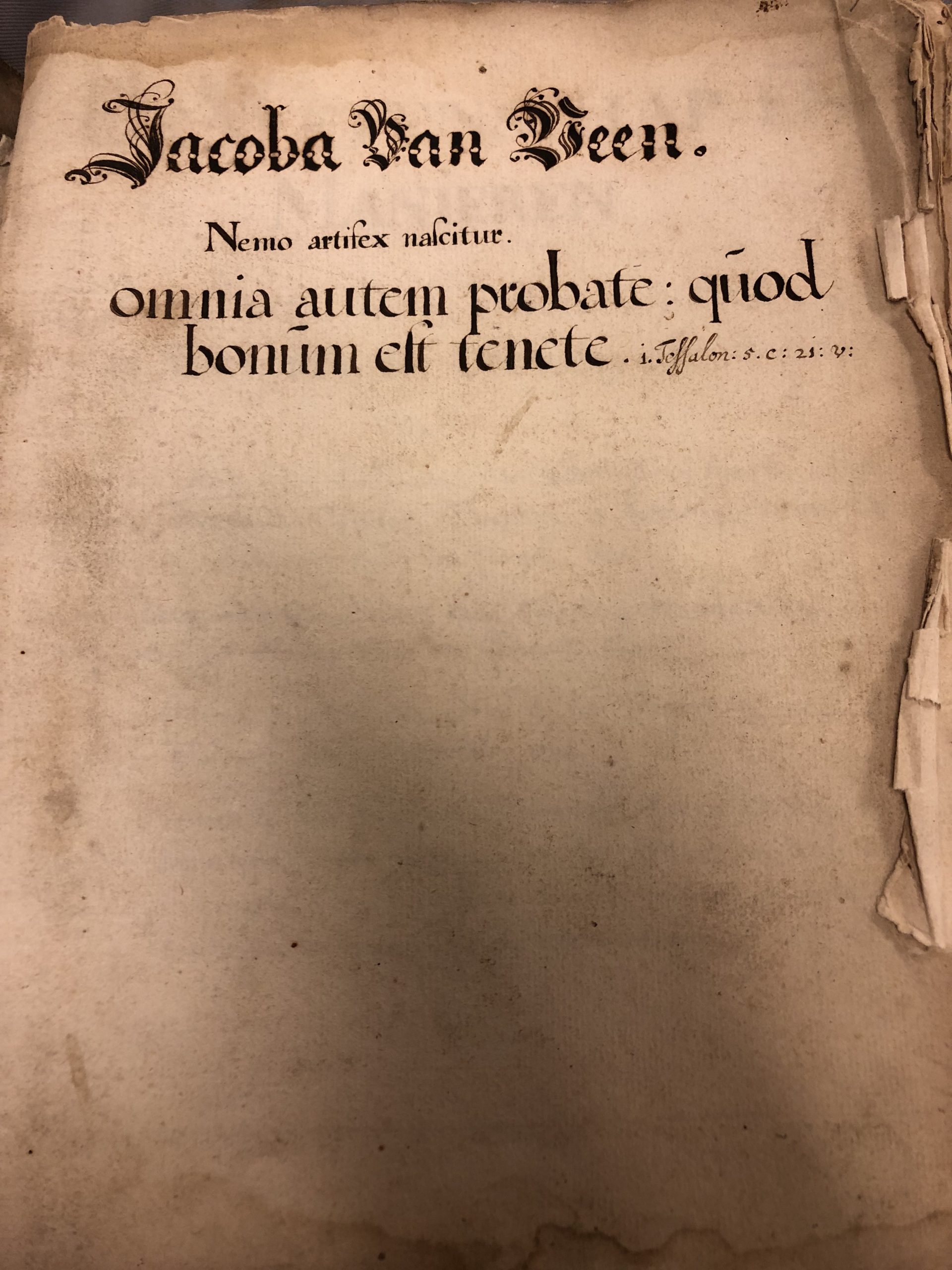

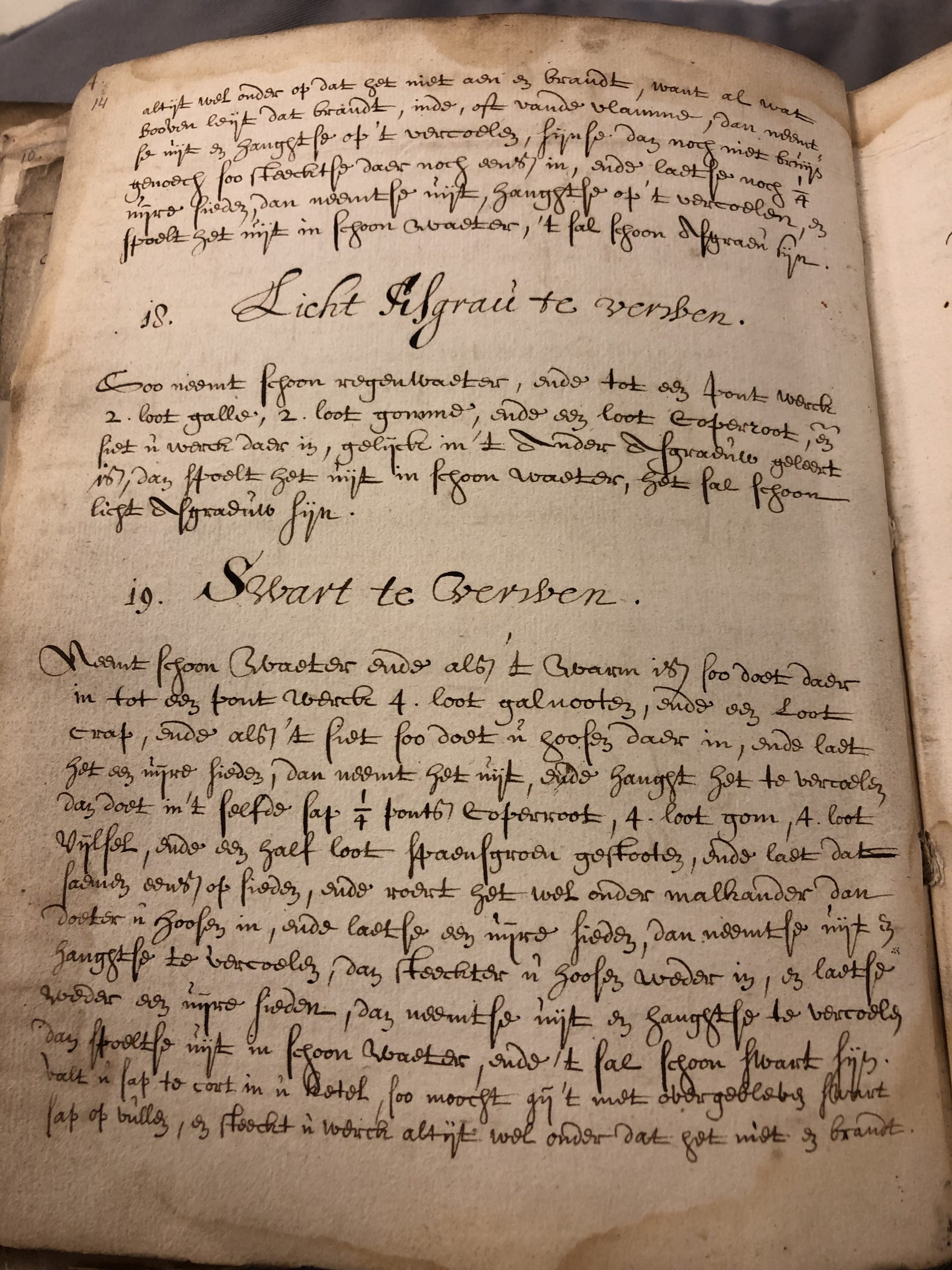

Een cleyn Verff-boecxken [67] is a small dyer’s manual printed in 1638 and was the source of one of our recipes. The copy of this rare surviving edition from which we worked had recently been acquired by the Rijksmuseum [Figure 17]. The booklet contains twenty-four dyeing recipes, among which two recipes are for black: ‘Om Swart te Verwen’ and ‘Een ander om swart te verven’. These recipes were reconstructed. Similar instructions are found in a seventeenth-century handwritten recipe book compiled by the Dutch writer and amateur artist Jacoba Van Veen (1633 – after 1687)[68] [Figures 18, 19 and 20].

As with the recipes in Conste des ververs, the recipes from Van Veen’s recipe book were rather impressionistic and less precise than a modern recipe for dye would be. ‘To dye black’ we learn here, one should ‘Take clean water and when it is warm add until one pond of work 1. Loot galls and 1 loot madder and when it Cooks add the stockings in there and leave it for one hour cooking then take it out and hang it to cool down Then in the same water a quarter pond iron(II)sulphate 4.loot gum 4. loot filings and half loot Spaens-groen pounded and let it all cook together steer it well and add the stockings back in and let it Cook for one hour then take it out and hang it to cool down then put the stockings back in and let it cook for one hour take it out and hang it to cool down rinse it with clean water and it will be beautiful black.’

The Combination of Blue Undertone Top-Dyed with Tannins and Metal Salts

We can observe increasing imports of logwood starting in the first half of the seventeenth century.[69] From the beginning of the seventeenth century on it was also applied as a blue undertone for black dyeing. Despite the rules, dyers were always on the lookout for cheaper ways to dye blue. Combinations of woad and indigo were used to dye cheaper blue fabrics.[70] The combination of a blue undertone (with indigo or woad, or with logwood) mordanted with tannins and metal salts gave a saturated black colour. Tannins like alder bark (Alnus glutinosa L.), sumac (Rhus coriaria L.), walnut husks (Juglans regia L.) and gallnuts (gall species) were also applied to mordant the wool and darken the colour. Gallnuts were employed both as mordant and colourant, producing grey or black shades in combination with metal salts such as iron and copper sulphate or iron acetate.[71] Those ingredients were applied in a second stage over a dark blue dyed undertone or in the blue dye bath, which, depending on the period, could be coloured with woad – from the Middle Ages onwards, logwood – from the early seventeenth century, and indigo – from the middle of the sixteenth century. A blue undertone was still often required, but only when over-dyed with a combination of iron sulphate or iron acetate in combination with tannin. This could happen in a separate bath, however, recipes have also been found combining the various ingredients in one single bath. The use of logwood and tannin is mentioned in the work of Jacoba van Veen and in Een cleyn Verff-boecxken from Gerbrandum Nicolai both written at the end of the seventeenth century (Figure 21). Similar recipes are also mentioned in a later work called De volmaekte verwer (‘The accomplished dyer’), from 1753.[72]

Conclusion

This article summarized the reconstruction of five historic recipes to dye black. The first two recipes require a preparational section and are labour and time-intensive. The first recipe combines a blue undertone top dyed with madder. The second recipe requires dyeing with a so called “lasagna” from the Plictho. An easy procedure that takes a few weeks before it is ready to dye with. A third group of recipes deriving from seventeenth-century manuscripts and a print booklet, Conste des Ververs, Jacoba Van Veen’s recipe book and Een cleyn Verff-boecxken, give instructions for dyeing without any time-consuming preparational steps that enable us to dye black instantly. Finally, another instant recipe combining a new ingredient, logwood, in combination with tannins and metal salts also found in Een cleyn Verff-boecxken was reconstructed.

These recipes have been dyed several times in recent years by students at the Universities of Antwerp, Utrecht and Amsterdam, by the dyers at Studio Claudy Jongstra and during an international summer university. Each time we arrived with the participants at different interpretations of the historic source texts which resulted in variations on the dyeing protocol and final dyeing results.

From the start, it was doubtful that the historical recipes found were viable when being followed to the letter. And whether the information found was adequate to understand the full technological process of black dyeing. In most cases metal salts and oxides were indispensable to obtain an intense black shade in combination with alder bark, sumac, and gallnuts, frequently used tannins that were added to the dye bath. The iron part can either be iron oxide, swarf, filings, old iron or a combination of several iron components.

The colour of the reconstructed sample could vary in intensity and hue as well as the tactility of the sample. Some samples were rougher to the touch than others. Some samples were more evenly dyed than others. And there were ultimately some failures. These reconstructions provide us with a better understanding of the precise actions of the dyes and mordants on the raw material. The influence of the technological steps on the final result and the importance of the sequence of steps became clear while reconstructing the recipes. The dyeing process was labour intensive and used expensive raw materials, which explains why black was an exclusive and expensive colour. It also appears that the number of times the fabric is immersed into the dye bath clearly determines the depth and intensity of the colour, but we also perceived a saturation point for some dyes suggesting that good dyers would have known very well how to achieve the best results with the most efficient methods.

The recipe reworkings showed us that dyers must have been well aware of different variations and techniques for dyeing black and it became apparent that colour-fast jet black as we know it today is very difficult to obtain. The introduction of logwood (described in the last method) resulted in a more easily attainable intense black. With the first and second methods, there appear to be only a few recipes that lead to a dark black result as we perceive it today. Obviously, we have to assume that today’s perception of the colour black is not the same as it was during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Though we can only speculate about the period’s eye for black fabrics, it is striking that when looking at paintings from the Burgundian era where black plays a very prominent role in fashion it appears that even the black paint used to paint the textiles is not monochromatic. We may wonder whether the depicted sovereigns and dignitaries intentionally had painted themselves in blacker garments than they could afford or obtain, or whether they preferred to be portrayed in reddish black to show that they were wearing the most expensive black that was top-dyed with a red dye on a dark blue ground colour. While many dye recipes end with phrases such as ‘repeat until black enough’ [74] it remains unclear what ‘black enough’ would have meant to a Burgundian dyer, or if this black enough would look ‘black’ to a modern eye.

Perception, personal taste and the prevailing fashion presumably played an important role in defining what was perceived as ‘sufficiently’ or ‘perfectly’ dyed black. Historical sources show that according to the darkness and the hue of the obtained colour, black shades were given different names. For example in sixteenth-century Antwerp, the following colour names for black were found: ‘moreit’, madder black or ‘meekrapzwart’, and black or ‘taneet’. The colour name ‘moreit‘ was also used for the precursor of madder black.[75] Before medieval dyers had gained mastery of dyeing colour-fast, high-quality blacks, dark fabrics apparently tended to be a dark purple- or violet- black rather than true black. In a later stage this violet black was not experienced as black anymore and shifted to the violet colours. Ultimately, we can to question the nature of ‘perfect black’, and began to ask how it related to other early modern colours. When we produced a number of dyed textiles, we frequently failed to produce a colour that appeared black to us, but often these failures proved to be most relevant for understanding the high art of black dyeing with natural colourants that dyers had mastered under Burgundian reign — an art form that has largely faded into oblivion with the rise of synthetic dyes in the modern era.

Bibliography

Braekman, W.L. Middelnederlandse verfrecepten voor miniaturen en allerhande substancien. (Brussel: Omirel Ufsal, 1986).

Brunello, Franco. “The Art of Dyeing in the History of Mankind”, (Neri Pozza, Vicenza, 1973).

Cardon, Dominique. “Natural Dyes, Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science”, (Archetype publications, London, 2007).

Cardon, Dominique. “Le monde des teintures naturelles”, (Belin, Paris, 2003).

Cardon, Dominique. “Des Couleurs pour les Lumières – Antoine Janot, teinturier Occitan (1700-1778)”, (CNRS Editions, Paris, 2019).

Coghen, Henricus. Conste des Ververs. Manuscript, (Leuven, Municipal Archives, cat.7133, 1619-1623).

Davids, Karel, “Craft secrecy in Europe in the Early Modern Period: A Comparative View, Early Science and Medicine”, (Vol. 10, No. 3, Openness and Secrecy in Ealry Modern Science, 2005), 341-348.

De Nie, Willem.L.J. “De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij van de veertiende tot de achttiende eeuw”, (Doctoral thesis, Leyden, 1937).

Dieu, Maurice. “Het verven der goederen te Leuven”, De Brabantsche Folklore, 11, (1932), 146-150.

Edelstein Sidney, M., Borghetti Hector C., Plictho of Gioanventura Rosetti: Instructions in the Art of the Dyers which Teaches the Dyeing of Woolen Cloths, Linens, Cottons, and Silk by the Great Art as Well as By the Common, Translation of the first Edition of (1548), The M.I.T. Press Masachusetts Institute of Technology, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England, 1973).

Edmonds, John. The History of Woad and the Medieval Woad Vat. Historic Dyes Series 1. Little Chalfont: J. Edmonds, (1998).

Frencken, Herman.G.T. “T Bouck và Wonder” (1544, Antwerp, Cock), PhD dissertation, university of Leiden, H.Timmermans, Roermond, (1934).

Gerbrandum, Nicolai. “Een cleyn Verff-boecxken inhoudende seer constighe saeyet verwen, nut en profytelijck voor breyders en oock voor andere persoonen die haer dit werck mede willen bemoeyen. Den tweeden druck, op nieuws overghesien ende verbetert.”, (Leeuwarden, 1638).

Hofenk De Graaff, Judith H. “Natural Dyestuffs, Origin, Chemical Composition”, Identification, (ICOM Committee for Conservation, Madrid 2001).

Hofenk De Graaff, Judith H. “The colourful Past, Origins, Chemistry and Identification of Natural Dyestuffs”, (Abegg Stiftung & Archetype Publications, 2004).

Hurry Jamieson, B. “The woad plant and its dye”, (Oxford University Press, 1930).

Jolivet Sophie, La construction d’une image : Philippe le Bon et le noir (14191467), Apparence(s) [Online], 6 | 2015, Online since 25 August 2015, Connection on 30 November 2018. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1307

Lookman Sharifa, “Experiencing Historical Techniques through the Color Black at the ROOHTS Summer School,” in Recipe Hypotheses, ed. Joshua Schlachet (UK: The Recipes Project: Food, Magic, Art, Science, and Medicine, 2019).

Ortega Saez, Natalia, “De technologie van het zwartverven”, (Tentoonstellingscatalogus meesterlijk zwart in mode & kostuum, MOMU, Lannoo, Antwerpen 2010) 57-65.

Ortega Saez, Natalia. “Black dyed wool in North Western Europe, 1680-1850 : the relationship between historical recipes and the current state of preservation”, (Doctoral thesis, Universiteit Antwerpen Faculteit Ontwerpwetenschappen, Antwerpen 2018).

Ortega Saez, Natalia e.a., “Material analysis versus historical dye recipes: Ingredients found in black dyed wool from five Belgian Archives (1650 – 1850)”, (Conservar patrimonio 31, 2019), 115-132.

Partridge, William, “A Practical treatise on dyeing of woollen, cotton and skein silk with the manufacture of broadcloth and cassimere”, (New York, 1823)

Posthumus, Nicolaas W. “Bronnen tot de geschiedenis van de Leidse textielnijverhied”, (6 volume, Martinus Nijhoff, ’S-Gravenhage, Vol. I, 1901) 52.

Rosetti, Gioanventura, The Plictho: instructions in the art of the dyers which teaches the dyeing of woolen cloths, linens, cottons, and silk by the great art as well as by the common”, facsimile and translation of the first edition of 1548. Ed: Sidney M. Edelstein and Hector C. Borghetty. (Cambridge and London: M.I.T. Press, 1969), 10 and 99

Schweppe, Helmut. “Handbuch der Naturfarbstoffe, Vorkommen, Verwendung, Nachweis”, (Ecomed, Landsberg/Lech, 1992).

Schweppe, Helmut, “Production of comparative dyeings for the identification of dyes on historic textile materials”, (sponsored by the conservation analytical Laboratory of the Smithsonian Institution Washington DC USA, 15th through 19th September 1986).

Smith, Pamela H., “In the Workshop of History: Making, Writing, and Meaning,” West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 19, no. 1 (2012): 5, 145.

Thijs, Alfons K.L. “Van “werkwinkel” tot “fabriek”; de textielnijverheid te Antwerpen (einde 15de-begin 19de eeuw)”, published part of doctoral thesis, Part I, (Brussels, 1987).

Thijs, Alfons K.L. “De Textielnijverheid en het stedelijk leefmilieu te Antwerpen, (15de – 18de eeuw)”, P. Maclot, W. Pottier ’N Propere Tijd!?, Onleefbaar Antwerpen thuis en op straat 1500-1800, (VZW Antwerpse Vereninging Voor Bodem-en Grondonderzoek, AVBG, 1988), 183-205.

Thijs, Alfons K.L. “De Technische Organisatie van de Antwerpse Textielbedrijven”, unpublished part of doctoral thesis, Part II, Antwerp, (1987).

Verhecken, Andre. “Conste des ververs: A Flemish Dyeing Manuscript form Leuven, 1619-1623”, e-preservation science, (2013), 59-65.

Verhecken, Andre. “Technische aspecten van de middeleeuwse wolververij in Diest, volgens 14e en 15e- eeuwse lakenkeuren”, Vlaamse Vereniging voor Oud en Hedendaags Textiel, (1992), 87-95.

Van Estveldt, Steven. “De volmaekte verwer, Alles leerende wat ‘er vereischt word, om alle wollen en zijden, met alle Couleuren, en HOEDEN, schoon zwart te verwen” (Amsterdam, 1754).

Van Veen, Jacoba. “De Wetenschap en[de] Manieren om alderhande Couleuren van Saij of Saijetten te Verwen …”, (Den Haag, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, 135 K44, 1635-1687).

Woudhuysen-Keller Renate, Das Farbbüechlin: Codex 431 aus dem Kloster Engelberg; ein Rezeptbuch über Farben zum Färben, Schreiben und Malen aus dem späten 16. Jahrhundert. Bd. 2 Bd. 2 (Zürich: Abegg-Stiftung, 2012).

[1] Ortega, De technologie van het zwartverven, 57-65.

[2] Thijs, De Technische Organisatie van de Antwerpse Textielbedrijven, 478.

[3] On the legendary taste for black dress of the third Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good (1396-1477), see the essay by Jolivet elsewhere in this volume.

[4] De Nie, De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij, 184-219.

[5] Partridge, A Practical treatise on dyeing, 138-144.

[6] MS Sloane 2052, fol. 93r, marginal note in red ink: “La corne de cerf/ bruslée, quand/ vous la broyés avec eau sur/ la pierre devient/ brune, comme/ une terre ou/ ocre. Laquelle/ si vous meslee/ avec huyle sur/ la palette, il/ se faict un noir comme jaget/ tresbeau, com-/me j’ay veu, q/ a besoing des/ additions ordi-/naires pour/ seicher. Ce q’l/ ne faict jamais/ de soymesme.” see: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=sloane_ms_2052_f093r, last accessed 28 April 2020.

[7] De Nie, De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij; Thijs, Van “werkwinkel” tot “fabriek”; Hofenk De Graaff, Natural Dyestuffs, Origin, Chemical Composition; Jolivet, La construction d’une image; Ortega, Material analysis versus historical dye recipes.

[8] The Melijn Archive consists of a number of trade letters and is located in two places: 1. the Fashion Museum of Antwerp, 2. the Municipal Archives of Wijnegem. The second part, at least the register synopsis, can be accessed online; http://www.heemkringwijnegem.be/melijn.php, last accessed 1June 2020. The part from the Fashion Museum can be consulted in the library of the museum. It includes a series of eleven documents that compile copies of the trade letters. The other documents are journals and commercial correspondence. The archive consists mainly of correspondence between Jan Michiel Melijn and commercial agents in England (London) concerning orders for woollen fabrics, which are to be delivered in a variety of price ranges, colours, and the enclosed sample.

[9] Ortega Saez e.a., “Material analysis versus historical dye recipes: Ingredients found in black dyed wool from five Belgian Archives (1650 – 1850),” 119-125.

[10] De Nie, De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij, 144.

[11] Thijs, De Technische Organisatie van de Antwerpse Textielbedrijven, 440-447; De Textielnijverheid en het stedelijk leefmilieu te Antwerpen, 183-205; De Nie, De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij, 140-143.

[12] De Nie, De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij, 142.

[13] https://artechne.wp.hum.uu.nl/burgundian-black/

[14] The following people participated in the workshop: Claudy Jongstra (textile artist), Annette Hoeben (natural plant dyer, Studio Claudy Jongstra), Anna Reggio (architect, Studio Claudy Jongstra) Natalia Ortega-Saez (University Antwerpen), Jo Kirby Atkinson (senior scientist, formerly of the Scientific Department, National Gallery, London), Ana Serrano (RCE), Art Proaño-Gaibor (RCE), Suzan Meijer (textile conservator RMA), Jenny Boulboullé, Sven Dupré (Uva & UU, ERC Artechne) Paula Hohti (U Aalto, PI ERC Re-fashioning the Renaissance), Suzanne Bul* (UvA, research master student technical art history), Jessie Chen* (UU, PhD candidate), Erma Hermens (UvA & RMA), Chrystel Brandenburgh (Brandenburgh Textile Archeology), Samuel Mareel, (Museum Hof van Busleyden). On the Burgundian Black Collaboratory, see also the contributions by Claudy Jongstra, Art Gaibor Proaño, and Jenny Boulboullé elsewhere in this volume.

[15] A study group called ‘Research On the Origin of Historical Techniques’, under the acronym ROOHTS, was established in 2018. The aims of ROOHTS were to acquire and further disseminate the theoretical knowledge and practical knowhow related to historical art technical sources and sources by heritage education and a broad audience. On the exhibition, see also the contributions by Claudy Jongstra and Samuel Mareel & Marijke Wienen elsewhere in this volume.

[16] https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/summer-schools/roohts-summer-school/

[17] Natalia Ortega Saez, Vincent Cattersel, (University of Antwerp), Sven Dupré, Jenny Boulboullé, (Utrecht University, Artechne), Art Proaño Gaibor, (Cultural Heritage Agency RCE), Birgit Reissland, Erma Hermens, (University of Amsterdam, UvA), Samuel Mareel, Marijke Wienen, (Museum Hof van Busleyden).

[18] Participants of the summerschool ROOHTS, Burgundian Black 2019, Griet Blanckaert, Cristina Cipriano, Charles Indekeu, Maria José Moreno Parada, Marie Hartmann, Marc Holly, Wilfried Pullinckx, Michelle Robinson, Sharifa Lookman, Younsool Shin, Guenevere Souffreau, Katia Weber, Young mi Yeo.

[19] Lookman Sharifa, "Experiencing Historical Techniques through the Color Black at the ROOHTS Summer School," in Recipe Hypotheses, ed. Joshua Schlachet (UK: The Recipes Project: Food, Magic, Art, Science, and Medicine, 2019). https://artechne.wp.hum.uu.nl/experiencing-historical-techniques-through-the-color-black-at-the-roohts-summer-school/

[20] De Nie, De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij; Thijs, Van “werkwinkel” tot “fabriek, 184.

[21] The term ‘reworking’ is more suitable for reconstructing historical recipes, as this term reflects the laborious aspect of making historical recipes in all its aspects. Sven Dupré and Jenny Bouloullé, Burgundian Black (Antwerp: University of Antwerp, Utrecht University, 2019); Hagendijk, Reworking Recipes. Reading and Writing Practical Texts in the Early Modern Arts. Dissertation, Utrecht University 29 June 2020.

[22] Smith, In the Workshop of History, 5, 145.

[23] Hofenk De Graaff, Natural Dyestuffs, Origin, Chemical Composition 35-36; Ortega, Black Dyed Wool in North Western Europe, 166-171.

[24] Ortega, Material analysis versus historical dye recipes,115-132.

[25] Ortega, Black Dyed Wool in North Western Europe, 166-167.

[26] For more information on these colorants, see also the essay by Kirby elsewhere in this volume.

[27] Hofenk De Graaff, Natural Dyestuffs, Origin, Chemical Composition, 35-36; Cardon, Natural Dyes, 20.

[28] In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the nomenclature for dye plants was diverse and not yet standardized. For the sake of clarity the modern Linnaean terminology is included where possible between brackets.

[29] Hurry, The woad plant and its dye, 22-27.

[30] De Nie, De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij, 98-119.

[31] Ortega, Material analysis versus historical dye recipes, 51-52.

[32] Hofenk De Graaff, The Colourful Past, 313-323.

[33] De Nie, De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij, 82-119; Thijs, De Technische Organisatie van de Antwerpse Textielbedrijven, 649-656.

[34] Thijs, De Technische Organisatie van de Antwerpse Textielbedrijven, 649.

[35] Hofenk De Graaff, The Colourful Past, 93; Cardon, Le monde des teinture naturelles, 101-110; Helmut, Handbuch der Naturfarbstoffe, 200.

[36] Thijs, Van “werkwinkel” tot “fabriek, 65; De Nie, De ontwikkeling der Noord-Nederlandsche textielververij, 188.

[37] Cardon, Natural Dyes, 139.

[38] Posthumus, Bronnen tot de geschiedenis, Vol. I, 52.

[39] Thijs, De Technische Organisatie van de Antwerpse Textielbedrijven, 651, 656.

[40] Partridge, A Practical treatise on dyeing, 138-144.

[41] Lighter and cheaper blue undertones were also dyed to obtain purple and green colors.

[42] Thijs, De Technische Organisatie van de Antwerpse Textielbedrijven, 651, 656.

[43] Ortega, Black dyed wool in North Western Europe, 79.

[44] Edelstein, Plictho, XI.

[45] Brunello, The Art of Dyeing in the History of Mankind, 178.

[46] Edmonds, The History of Woad and the Medieval Woad Vat, 31-34.

[47] Hurry, The woad plant and its dye, 33.

[48] Studio Claudy Jongstra and David Santandreu, (Indigo a most precious blue, Damme, 2019).

[49] For more information on Noir de Flandre, see also the essay by Boulboullé elsewhere in this volume.

[50] Cardon, Natural Dyes, 409.

[51] Hofenk de Graaff, The Colourful Past, 156; Cardon, Natural Dyes, 12-15.

[52] Cardon, Natural Dyes, 40-46; Hofenk De Graaff, The Colourful Past, 315.

[53] Thijs, De Technische Organisatie van de Antwerpse Textielbedrijven, 662.

[54] Hofenk De Graaff, The Colourful Past, 313-323.

[55] Om een swerte cupe te setten’, HS 1317, Library of Rijksuniversiteit Gent, ‘Om zwart linen doec te verwen’, MS 517, Wellcome Historical Medical Library, London (Braekman 1986) (15th century).

[56] Davids, Craft secrecy in Europe in the Early Modern Period, 341-348.

[57] Edelstein, Plictho, 89.

[58] The “Plictho” was translated into English in 1969 by Edelstein Sidney, M., Borghetti Hector C.: Instructions in the Art of the Dyers Which Teaches the Dyeing of Woollen Cloths, Linens, Cottons, And silk by the Great Art as Well as by the Common, Translation of the first Edition of (1548). The M.I.T. Press Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England, (1973).

[59] For more information, see also the essay by Kirby and Boulboullé elsewhere in this volume.

[60] Renate Woudhuysen provides a concise description of how to dye with the alder bark vat in her critical edition of the German Farbbüchlein, perfectly suited for those who want to try this at home with a water dispenser: 'In ein kleines fass, mit einem zapfen unten am Boden, legt man lagenweise gedörrte Erlenrinde und rostiges Eisen, bis das Fass voll ist. Dann giesst man Wasser darauf und lässt es 14 Tage lang stehen, je länger, je besser. Nach der niederländischen Methode lässt man die Tonne bis zu 6 Wochen stehen und giesst zweimal in der Woche die Flüssigkeit um, idem man sie unten abzapft un oben wieder afgiesst. Zum Färben lässt man von der Flüssigkeit in den Färbekessel ab, erhitzt sie zum Sieden und stösst dann das gebeizte Tuch hinein. Wenn es schwarz genug scheint, lässt man es abkühlen, das heisst oxidieren, und danach spült man es kalt aus. Man wiederholt das Färbe und Spülen ein-bis zweimal, um ein genüggend tiefes Schwarz zu erzielen'. Woudhuysen-Keller, Das Farbbüechlin, vol. 2, 43-47. In English, translated Jenny Boulboullé, 'In a small vat, with a stopper/bung at the bottom, you put dried alder bark and rusty iron swath in layers until the vat is filled to the top. Then you pour water on top and leave it for at least 14 days, the longer the better. According to the Dutch method you let it rest for up to 6 weeks and twice a week you fill the vat at the top with the liquid that you have first tapped off at the bottom to improve the mixture. For dyeing, you tap liquid from the vat, and you bring it to boil [in another dye vat] and you thrust the cloth into it. When it appears to be black enough, you let it cool down, this is called oxidizing, and then you rinse it in cold water. You repeat the dyeing and rinsing one or two times to achieve a sufficiently deep black colour'.

[60] Renate Woudhuysen provides a concise description of how to dye with the alder bark vat in her critical edition of the German Farbbüchlein, perfectly suited for those who want to try this at home with a water dispenser: 'In ein kleines fass, mit einem zapfen unten am Boden, legt man lagenweise gedörrte Erlenrinde und rostiges Eisen, bis das Fass voll ist. Dann giesst man Wasser darauf und lässt es 14 Tage lang stehen, je länger, je besser. Nach der niederländischen Methode lässt man die Tonne bis zu 6 Wochen stehen und giesst zweimal in der Woche die Flüssigkeit um, idem man sie unten abzapft un oben wieder afgiesst. Zum Färben lässt man von der Flüssigkeit in den Färbekessel ab, erhitzt sie zum Sieden und stösst dann das gebeizte Tuch hinein. Wenn es schwarz genug scheint, lässt man es abkühlen, das heisst oxidieren, und danach spült man es kalt aus. Man wiederholt das Färbe und Spülen ein-bis zweimal, um ein genüggend tiefes Schwarz zu erzielen'. Woudhuysen-Keller, Das Farbbüechlin, vol. 2, 43-47. In English, translated Jenny Boulboullé, 'In a small vat, with a stopper/bung at the bottom, you put dried alder bark and rusty iron swath in layers until the vat is filled to the top. Then you pour water on top and leave it for at least 14 days, the longer the better. According to the Dutch method you let it rest for up to 6 weeks and twice a week you fill the vat at the top with the liquid that you have first tapped off at the bottom to improve the mixture. For dyeing, you tap liquid from the vat, and you bring it to boil [in another dye vat] and you thrust the cloth into it. When it appears to be black enough, you let it cool down, this is called oxidizing, and then you rinse it in cold water. You repeat the dyeing and rinsing one or two times to achieve a sufficiently deep black colour'.

[61] Edelstein, Plictho, 10 and 99.

[62] Gerbrandum, Een cleyn verff-boecken 8; Van Veen, De Wetenschap en[de] Manieren om alderhande Couleuren.

[63] Coghen, Conste des ververs; Verhecken, Technische aspecten van de middeleeuwse wolververij in Diest, 87-95; Verhecken, Conste des Ververs 59-65; Dieu, Het verven der goederen te Leuven, 146-150.

[64] Dieu, Het verven der goederen te Leuven, 146-150.

[65] Verhecken, Technische aspecten van de middeleeuwse wolververij in Diest, 87-95, Verhecken, Conste des Ververs, 59-65.

[66] See on reworkings of recipes for dyeing stockings also the essay by Art Gaibor Proaño, elsewhere in this volume.

[67] Gerbrandum, Een cleyn verff-boecken, 8.

[68] Van Veen, De Wetenschap en[de] Manieren om alderhande Couleuren; see also http://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/bwn1780-1830/DVN/lemmata/data/Veen, https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_zev001200201_01/_zev001200201_01_0013.php last accessed 15 June 2020.

[69] For more information on these colorants, see also the essay by Kirby elsewhere in this volume.

[70] Thijs, De Technische Organisatie van de Antwerpse Textielbedrijven, 558.

[71] Cardon, Natural Dyes, 409.

[72] Van Estveldt, De volmaekte verwer.