In the fall of 2020 two special loans were added to the permanent display at Museum Hof van Busleyden in Mechelen. The first were three sixteenth-century portraits from the collections of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels: one of Mary of Austria, the daughter of Charles V, after Anthonis Mor, and two of unknown male individuals by Willem Key. The second set consisted of three cloaks from Spiritual Glamour, the fall/winter 2019–2020 haute couture collection by the Dutch fashion house Viktor&Rolf [Figures 1 and 2].

Black cloth linked these two sets of objects. The three sitters in the sixteenth-century portraits wear rich black garments, which have been reproduced in stunningly realistic detail through oil paint on panel and canvas. The beauty and variety of black is even more direct in the Viktor&Rolf cloaks in felted wool, where the black has been contrasted and enhanced by mixing it with other colours such as deep indigo blue and warm madder red.

Video 1: The Burgundian Black Collaboratory, an expert workshop at Claudy Jongstra’s farm in Friesland from 16 – 18 January 2019, film by Joshua Pinheiro Ferreira, PADRE FILMS (https://padrefilms.com/) for the Back to Black exhibition at Museum Hof van Busleyden.

Museum Hof van Busleyden borrowed the portraits from the Royal Museums of Fine Arts and the Viktor&Rolf cloaks as part of its Back to Black presentation, which ran from summer 2019 through summer 2021. Back to Black unravels, for the museum visitor, a more nuanced and suggestive link between the portraits and the cloaks: how, to be precise, the first has led to the second. Representations of rich black garments in portraits from the Burgundian period, such as the ones on display, stand at the outset of a collaborative project between the Dutch textile artist Claudy Jongstra, the research group Artechne (Utrecht University and University of Amsterdam), and Museum Hof van Busleyden, in collaboration with the Department of Conservation and Restoration at the University of Antwerp and the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency Research Laboratory. The aim of the project was to find out how much of the knowledge and expertise that lies behind these beautiful Burgundian blacks can be retrieved and how it can be used to enrich our experience and use of colour today. One of the most remarkable outcomes of the project so far is Viktor&Rolf’s Spiritual Glamour collection. The cloaks from this collection are made from felted wool from sheep with plant-based colourants that are — as much as possible — cultivated by Studio Claudy Jongstra in collaboration with local farmers and at Jongstra’s own farm in Friesland.[1] The felted wools were dyed black following historical recipes that have been unearthed and re-produced in the context of this project.

In this essay we present the museological setup of Back to Black and how it fits within both the Burgundian Black collaboration and the general concept of Museum Hof van Busleyden. We pay special attention to museological research and audience participation, one of the guiding principles of the Mechelen museum.

Displaying Burgundian Black: The Exhibition Back to Black

The collaboration between Jongstra, the research teams from Utrecht, Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Mechelen began in the spring of 2018, about a year before the opening of the exhibition. It roughly consisted of three phases. The first was archival research aimed primarily at finding historical recipes for the black dyeing of cloth, dating from the ‘long’ Burgundian period, i.e., the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries. On the basis of these recipes, the Artechne team co-organised two re-working workshops with Jongstra and her team at the artist’s farm in Friesland. During the first expert workshop an international team of researchers, educators, and museum professionals together with the master dyers of Studio Claudy Jongstra tried to put the historical recipes into practice as rigorously as possible.[2] The third preliminary phase took place in Jongstra’s studio and consisted of integrating the knowledge gained during the workshops into Jongstra’s practice as a textile artist.[3]

Each of these three preliminary phases has been represented in the Back to Black setup in Museum Hof van Busleyden, which occupies three spaces throughout the permanent display of the museum. One room has been devoted in its entirety to the project. Transcriptions of the historical recipes and lists of the ingredients required have been put up on one of the walls. The recipes are illustrated with small samples of cloth dyed during the interdisciplinary workshops. They allow the visitor to discover how different ingredients, recipes, and materials lead to different kinds of black cloth. Next to the recipes is shown a brief video documentary of the workshops on Jongstra’s farm [Figure 3; see also Video 1 (above)].

At the opposite end of the room a wall with raw materials, plants in different stages of processing, and colourant extractions evoke the look, sense, and smell of a real workshop, thus re-creating the sensory experience of the makers’ space [Figure 4]. Through it, visitors gain insight in the materials and techniques used in Jongstra’s creative process as well as in the results of the experiments conducted at her farm. Labels explain what the visitor is seeing but also further enhance the sense of richness and variety in the creation of black.

Hung in the entry hall, at the very beginning of the museum parcours, Foundations of Black, a monumental work by Studio Claudy Jongstra, is an early result of the artist’s experimentation with historical recipes [Figure 5]. There is actually no black in this work. Rather it is built up of the different colourants similar to those used during the Renaissance to attain the perfect black: walnut, European woad, Asian indigo, Dutch madder, and cochineal from Mexico and the southwestern United States. This work also reflects on the geopolitical significance of dyeing techniques refined during the Burgundian period for attaining the perfect black. The availability of high-quality colourants was a direct result of the colonization in the Americas by Spain and Portugal, two close allies of the House of Burgundy.[4]

The three cloaks by Viktor&Rolf are displayed in the attic of the museum, at the other end of the parcours. They have been placed on an elevated elongated plateau, resembling a fashion runway. On two screens visitors can discover short clips showing the presentation of Spiritual Glamour during the 2019 Paris fashion week and a visit of Viktor Horsting and Rolf Snoeren to Jongstra’s farm and studio in Friesland.

Video 2: Project trainee Laura Van Kins examines the input of visitors who added more than 835 cards with their spontaneous “black” associations. (video fragment vlog #1 ©Museum Hof van Busleyden)

Back to Black is more than a museological post factum report of a preliminary research project, however. Through active engagement with the museum visitor, it also aims to supplement the scientific research and artistic creation around the Burgundian Black project. A participatory set-up, for instance, encourages visitors to contribute by asking them to write down their personal response to the black textile samples presented there. All the visitors’ reactions put together constitute an impressive ‘stock’ of contemporary associations with black textile. A wall representing the growing public response forms a dynamic display in the exhibition [Figure 6].

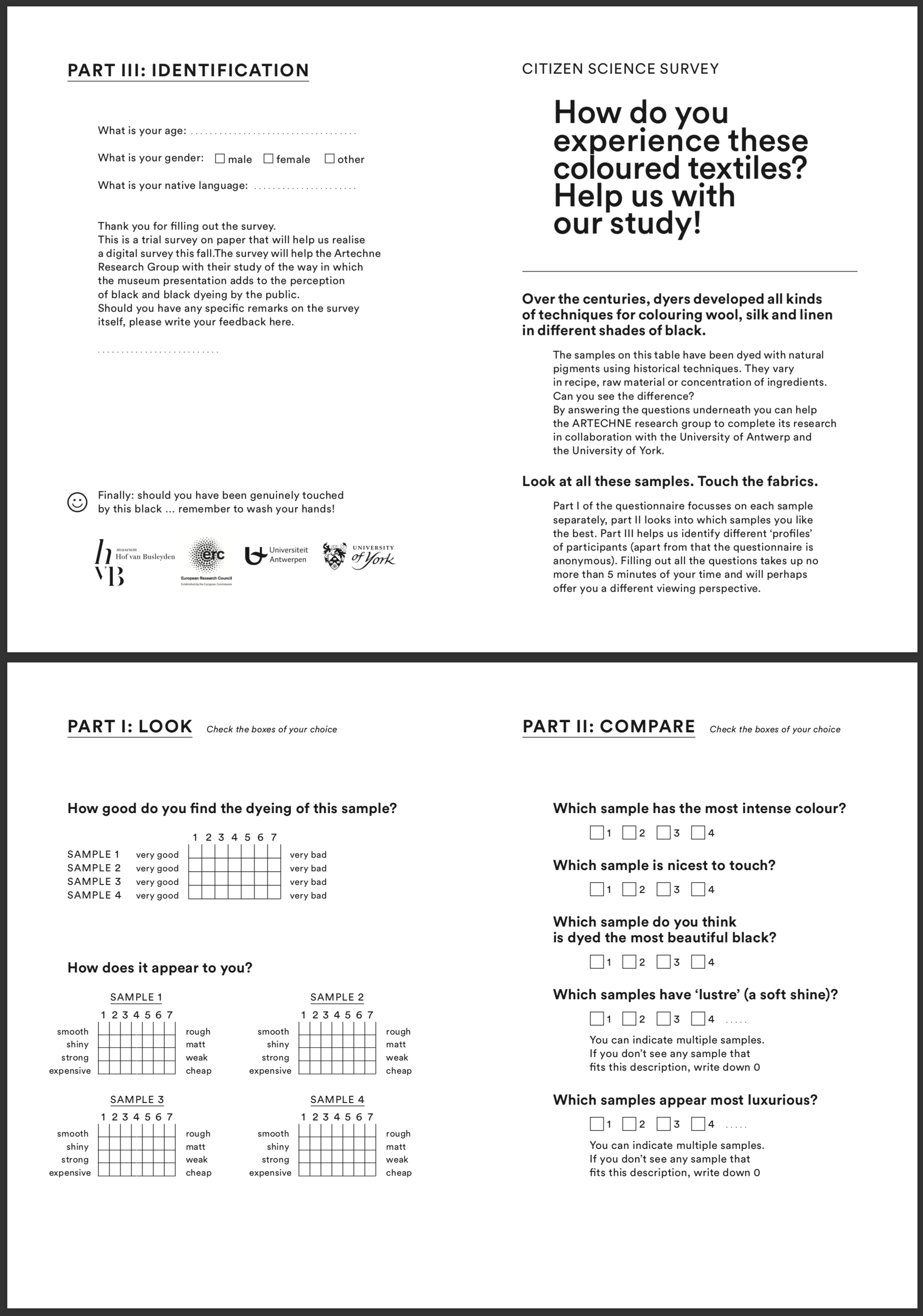

A second table hosts a basic questionnaire that screens people’s perception of a set of dyed textile samples, taken from the historic dyeing process during the re-working project at Studio Claudy Jongstra. Visitors are prompted to compare the exhibited samples of wool fabrics, dyed black following different historical recipes. They can examine them closely, touch them, and smell them. They can share their observations and responses in a public (anonymous) survey that the museum has designed in collaboration with the Artechne research group and Asifa Majid, an expert in colour-perception research at the University of York [Figure 7].[5] The result will contribute to a better understanding of the sensory perception of colours in museum contexts. It can also tell us whether information on the colour making processes and historical dye workshop experiences can influence visitors’ perception of colours.

In the middle of the room, an artwork by Claudy Jongstra, entitled Expanding Field, enters into dialogue with the historical objects. The installation itself is inviting to touch and, in order to enhance the public’s experience, visitors can become part of the artistic process. In different dyeing workshops, school groups and individuals can create black-dyed strands of wool that are added to the artwork. It is a collaborative piece of art that continues to grow with the input of the public, hence the name.

Museum Hof van Busleyden

Back to Black is not a standalone exhibition. Rather it is fully integrated into the fabric and goals of Museum Hof van Busleyden. This museum is housed in the former city palace of Hieronymus van Busleyden, a priest, lawyer, humanist, and diplomat who lived in the building between 1504 and his death in 1517 [Figure 8]. A recently graduated doctor in law from the University of Padua, Van Busleyden had moved to Mechelen after being appointed councillor at the Great Council, the highest legal court in the Low Countries at the time. During his thirteen-year residency in the city, Van Busleyden expanded the Hof van Busleyden from a modest house into a lavish city palace and one of the first Renaissance buildings in the Low Countries. He filled it with an extensive collection of books, Roman coins, musical instruments, and works of visual art. Prominent humanists such as Desiderius Erasmus and Thomas More were Busleyden’s guests in Mechelen and have praised their host and his dwelling in their writings. The Hof van Busleyden was probably a model for the ideal humanist dwelling of Eusebius in Erasmus’ colloquium ‘Convivium religiosum’ (1522).[6]

Museum Hof van Busleyden explores the historical and cultural context in which Van Busleyden lived and worked: the Burgundian–Habsburg Low Countries. A special focus in the museum lies on the city of Mechelen. Since the reign of Duke Charles the Bold (1467–1477), this medium-sized lordship situated halfway between Antwerp and Brussels has played an increasingly important role in the Burgundian lands. It owed this position mainly to its loyalty towards the House of Burgundy, which is still reflected in Mechelen’s present-day motto, ‘In fide constans’ (‘Loyal in faith’). Charles the Bold installed several of the institutions by means of which he aimed to strengthen the centralised Burgundian state in Mechelen, such as the Rekenkamer (a sort of ministry of finance) and the Great Council. The function of Mechelen as a proto–Burgundian capital attracted an important crowd of functionaries such as Van Busleyden, who built lavish residences throughout the city.[7]

During the regency of Charles the Bold’s granddaughter, Margaret of Austria, Mechelen would become a court city as well. Margaret had taken up residence in Mechelen in 1507 to oversee the education of her godson Charles of Habsburg, the later Charles V. She would also reign over the Low Countries in Charles’s name. Quiet, affluent, and loyal, Mechelen was deemed a better and safer environment to raise the future emperor than the political snakepit of Brussels.

The presence of Margaret of Austria and the court gave Mechelen a cultural boost that is hard to overestimate. Like many cities in the Low Countries, Mechelen had acquired its wealth during the Middle Ages through the production, processing, and trading of cloth. While the city had its own artist guild of Saint-Luke, the artists that gave Mechelen its international lustre mainly came from elsewhere and were attracted by the court and the wealthy clientele in and around it.[8] Foreign artists, such as the sculptors Conrad Meit and Jean Mone, the painter and engraver Jacopo de’ Barbari, and the producer of musical manuscripts Petrus Alamire, took up residence in the city, while Netherlandish artists such as Jan Gossart, Bernard van Orley [Figure 9], and Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen frequently travelled to the city from nearby Antwerp and Brussels.[9]

After the death of Margaret of Austria in 1530 and the subsequent move of the court to Brussels, most of the high-profile artists left Mechelen. The city remained an important centre for artistic crafts. In the numerous workshops that were established in Mechelen during the sixteenth century, alabaster sculptures, polychrome wooden statues known as poupées de Malines (‘Mechelen dolls’), gilded leather, and relatively cheap paintings in watercolour on canvas were produced on an almost industrial scale. They were exported throughout Europe and often also towards Portuguese and Spanish colonies in the Americas and in Asia, via the international trade and port centre of Antwerp. It is believed that Ferdinand Magellan took a poupée de Malines with him on his voyage around the world in 1519–1521.[10]

Burgundian-Habsburg Heritage Today

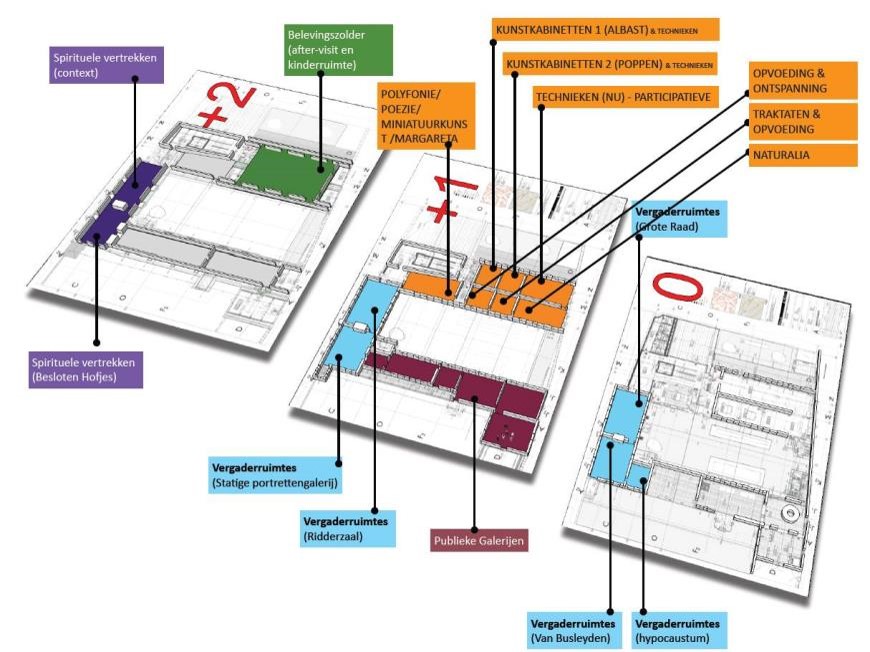

Throughout a sequence of five zones, dedicated to (1) public culture, (2) the culture of power, (3) creativity and discovery, (4) private life, and (5) contemplation [Figure 10], Museum Hof van Busleyden tells the story of the Burgundian and early Habsburg Low Countries, with a particular focus on the city of Mechelen. This is done by combining evocative historical and contemporary objects, such as works of art, books, material culture, multimedia applications, and wall texts. The genius loci of the Hof van Busleyden, which runs throughout the five zones, is the humanist culture that constituted the intellectual universe of Hieronymus van Busleyden. From the onset of the project to transform the old Mechelen municipal museum into a museum about the Burgundian and early Habsburg Low Countries, it was clear to all those involved that in order to do justice to the Renaissance humanist heritage of the Hof van Busleyden we could not limit ourselves to a historical narrative and its artistic and material remains. We also wanted to integrate one of the defining features of Renaissance humanism — its belief in the didactic value of historical knowledge — and we did so through the consummate humanist values of translatio, imitatio, and aemulatio. The example of the past, we believe, can bring about a renewal — a renaissance — of the present, and this principle informs our programming.[11] During the course of the realisation of the new museum, we frequently recalled Walter Benjamin’s famous claim that ‘every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably’.[12] From this perspective, the museum consistently confronts the Burgundian history with contemporary stories and reflections on the future. It makes explicit room for the input of communities and citizens throughout the permanent presentation, thus creating an active dialogue between past, present, and future. Museum Hof van Busleyden is therefore as much a museum about the present reflection on the Burgundian–Habsburg heritage as it is about the Burgundian-Habsburg period itself. It also aims to investigate what this period can mean for our contemporary world.

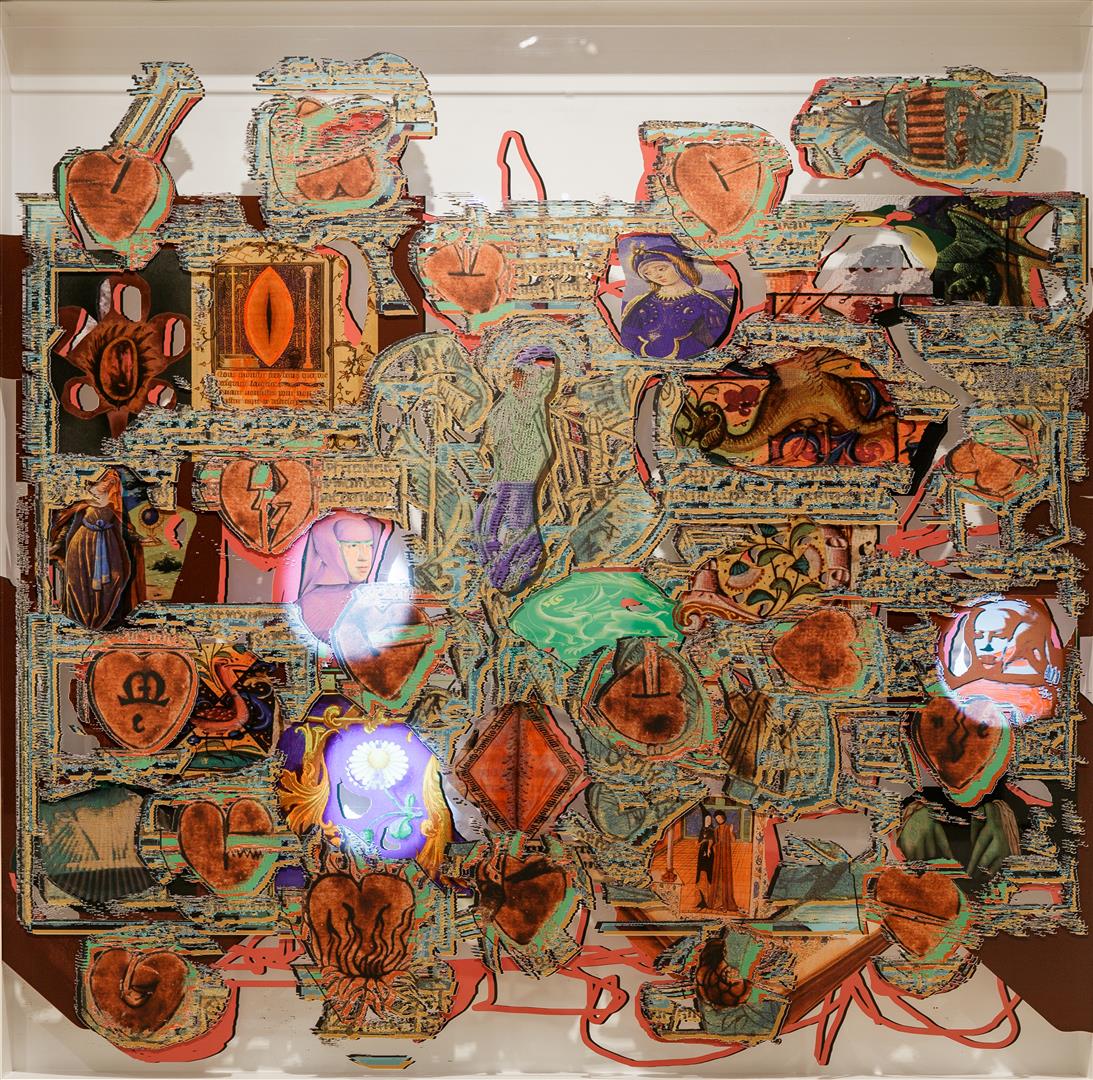

Since the renewed interest, fuelled by nationalistic feelings, in ‘early Netherlandish painting’ in the nineteenth century, and especially since the famous 1902 exhibition in Bruges of works of the ‘Flemish primitives’, contemporary artists have increasingly interacted with themes, artworks, iconographies and techniques from the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Low Countries.[13] In the permanent exhibition of Museum Hof van Busleyden, objects from the Burgundian–Habsburg period are thus confronted with more recent works of art, such as a depiction of a puppet theatre performance at the court of Margaret of Austria by the nineteenth-century Mechelen painter Willem Geets, and an engagement by contemporary Antwerp artist Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven with the visual symbolism surrounding Margaret of Austria [Figure 11].

If we want to understand how the Burgundian-Habsburg heritage has determined or can determine the present we cannot limit ourselves to the labour of curators, researchers, and artists. The voices of a broader spectrum of the public should also be integrated into the dialogue. Museum Hof van Busleyden is the result of a five-year participative process in search of a new museum concept.[14] Participation lies at the core of the organization: the creation process for Back to Black included considerable consultation with various communities around Mechelen and beyond, and their input was and is cardinal to the presentation. This multi-perspectival impulse means that Museum Hof von Busleyden considers interaction as essential to our work, from the initial stages of planning through execution. We respect academic perspectives, as well as the ideas and opinions of the public, who are, in turn, confronted with contemporary forms of artistic interpretation and practice with which they interact again.

Three participatory rooms are interwoven through the permanent presentation of the museum.[15] They build on the same themes as the historical rooms and also directly follow them. As the final room in the zone dedicated to public life, for example, The People Make the City presents three community associations from contemporary Mechelen. They represent the multitude, complexity, and diversity of urban life today. The room is the contemporary counterpart of the permanent exhibition rooms on the social fabric of the Burgundian city preceding it. Every two years, three new Mechelen organisations present themselves here, in co-creation with the museum.

In the rooms on the Burgundian culture of power lies the space for The Ground of Things (a collaboration with the local theatre company ARSENAAL/LAZARUS). This project considers the meaning of power, ownership, and natural resources in the commons today. All inhabitants of Mechelen are given a (virtual) equal share of their city, namely one m², to envisage a project that would benefit the common interest. The proposals are presented to the public in the museum, which also actively engages in social debate about them. In 2021 the city of Mechelen will make 20,000 m² available to realise a selection of projects. The museum and its theatre partner facilitate negotiations between the citizens to make this selection. This project is an interactive experiment where a museum and a theatre look for common ground and try to infuse the notion of common interest with the inhabitants of a city. The entire process of The Ground of Things is an exercise in contributive democracy, where cultural institutions act as a driving force for social and political innovation.

The third participatory space closes the zone on ‘creativity and discovery’. In 2018–2019, its first year of operations, the museum asked Hans Martens, the director of the Mechelen academy of arts and a prominent figure in the contemporary arts scene, to make a selection of works by contemporary artists, including Sofie Muller and Pascale Marthine Tayou. It reflected on the artistic craft production that Mechelen was famous for in the Burgundian–Habsburg period. These works also symbolise the close interaction between art and science that was typical for this era [Figure 12]. Following this exhibition, the same participatory space now houses the exhibition Back to Back until summer 2021.

Back to Black was born out of the ambition to bring about more interaction between historical and scientific research, audience participation, and contemporary creation. Among these facets, we found it most difficult to stage and present research. While research insights are important for any museum, they always remain somewhat subservient to the museum’s goals. Museums generally only integrate the results of multidisciplinary research, in its final form as input for museum texts or multimedia applications; research processes and practices remain largely invisible. There are numerous science museums that include experimental set-ups, but they are almost always limited to the natural sciences. With Back to Black we were wondering if it would be possible to show humanities research as a process rather than simply integrating its results into museum displays.

Back to Black as a Participatory Museum Project

What was the background and wider theoretical scope that gave rise to the fundamentally new participatory museum concept and what does a focus on participation actually imply for day-to-day museum operations? In what follows we present an analysis of key ideas and concepts that undergird the participatory presentations in the museum.

Participation is a complex concept and is hard to pin down. Even within the cultural sector, it has many meanings, nuances, and connotations. Participation is inherent to cultural heritage because heritage is always community-based and is the result of an interaction between people and places through time.[16] In the context of an art museum, participation has varying goals, such as individual meaning-making of an artwork by a single visitor, giving audiences a challenging experience, engaging the public physically, or creating social and/or artistic communities.[17]

Museums worldwide are becoming increasingly participative, seeking to involve, and work with, audiences. In this way they aim to be more relevant for present and future generations, promote social inclusion, and widen and develop audiences.[18] However, this participatory practice also raises new questions, such as: How can we link participation with the more traditional functions of a museum, namely acquiring, conserving, researching, communicating, and exhibiting? How do we make our participatory practice flexible enough to respond effectively to a diversity in types of audiences, either in age, background, or social status? Do citizens and communities actually wish to be connected? How do we design participatory projects in such a way that they truly empower citizens and make them part of the decision-making process?[19]

There is no unambiguous answer to these questions. Museum Hof van Busleyden integrated different perspectives on participatory work into one overall concept: (heritage) communities have a permanent place in the museum’s parcours, contemporary art goes into dialogue with artworks and objects from the Burgundian period, educational programmes are made in co-creation with the most vulnerable social groups in order to raise inclusiveness, and research is fed by audience engagement in order to express a more multivocal view on museum objects and narratives. In the Back to Black presentation we wanted to combine scientific research with audience engagement.

The set-up of Back to Black as a participatory room in the permanent routing of the museum tries to address a few of the above questions that we ask ourselves about our participatory work. It was conceived according to the guiding principles of participatory design as laid out in reference works such as Nina Simon’s The Participatory Museum (2011) or Pat Neuville and Anne Rowson-Love’s, Visitor-Centered Exhibitions and Edu-Curating in Art Museums (2017). The presentation makes use of traditional exhibition models to reproduce the three phases of the collaborative project in a visual display. Nevertheless the exhibition’s storytelling is underpinned by participatory techniques.

The Back to Black presentation is designed to invite people to participate. But a mere ‘open’ invitation is rarely successful. People would just feel out on a limb. A truly effective participatory exhibit offers visitors sufficient ‘scaffolding’ so they feel comfortable enough to go into interaction.[20] This technique is put into practice in one of the installations in the exhibition room. On a board, visitors are invited to express their association with the term ‘black.’ The question is open enough to motivate them, but we provide them with fixed tools, such as cut-out black drawing cards and white pencils. In this way they do not get overwhelmed by the breadth of possibilities. The success of this approach is shown in the high number of responses we received to date (March 2020): 835 visitors added their personal association with black.[21] They include one-word responses, personal reflections, quick sketches or symbols, but they all fit onto the cut-out black cards. The cards are displayed in the room and serve as ‘conversation pieces’ with which subsequent visitors can enter into interaction with others. The display of the cards makes the visitor feedback an integral part of the exhibition.

A co-creative process lies at the core of this exhibition concept and was already followed throughout the design of the room. There was not just the one curator, but an integrated exhibition team, including representatives for the academic, artistic, curatorial as well as the educational aspects. This team-curatorial approach is a lever towards an exhibition design that acts as an interface between the research project and the visitors, with plenty of room for multiple viewpoints.

The curatorial team embedded the design concept with educational resources—preferably non-textual and non-authoritative. The aim was to anticipate on different visitor backgrounds and their information needs as well as to support individual meaning making. An example of how this concept is integrated in the Back-to-Black exhibition are the transcriptions of the historical recipes put up on one of the walls.

Many of these recipes circulated widely in the past. They formed the basis for the re-enactment dye workshops at the start of the project. The recipes are combined with samples of cloth showing the different dying stages and results. They are inviting to touch and they let visitors discover how different ingredients, recipes and materials lead to different kinds of black. In this way the relatively complex surviving textual sources, which constitute an important part of our cultural heritage, are rendered accessible for a broad and diverse audience.

The museum not only anticipates on different visitor backgrounds, but also tries to cater for a broad spectrum of visitors, who desire different types of museum interaction. Therefore we offer diverse tools for diverse target groups. The participatory display in the room is accessible for all individual visitors. School groups can register for a more in-depth approach in a museum class where they get a hands-on taste of the work of the Burgundian craftsmen. More specialist groups as well as individual visitors with a greater interest in the topic can subscribe to a full-day historic dying masterclass in collaboration with the textile department of the Mechelen Arts Academy. Representatives from both the Academy and the Mechelen Fashion School took part in the collaborative expert dye workshops organised by the Artechne research group, so they could share this knowledge with a broader public.

Expanding Field, the artwork by textile artist Claudy Jongstra further pursues visitor engagement in the presentation as it is designed to be completed by the public, adding strands of wool they dyed themselves in the museum workshops. In order to widen our reach and further develop audience engagement, the museum always tries to make a connection with communities with little museum experience. For Back to Black these were the high school students from the Mechelen Fashion School, that integrated the project into a full year’s theme for their classes. The students organised their own dying workshop to re-create the historical blacks; they also designed new work inspired by this process and by Burgundian clothing in sixteenth-century paintings. The museum fed them with the necessary historical background and acted as the location for their fashion photoshoot and graduation exhibition.

Back to Black investigates how a symbiosis of presentation, participation and research strengthens the meaning and experience of black in the Burgundian period for museum visitors and how visitors simultaneously provide input for academic research. This project crystallises, in a highly imaginative way, the museum’s vision in which the cross-fertilization between knowledge and art and between the past and the present leads to new insights involving audiences in this process of co-creation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arnstein, Sherry R. “’A Ladder Of Citizen Participation,” Journal of the American Planning Association, 35: 4 (1969), 216–224.

Bienkowski, Pjotr. “No Longer Us and Them: How to change into a participatory museum and gallery. Our Museum Final Report 2016” (London, Paul Hamlyn Foundation, 2016), 4

Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, ed. with introduction by Hannah Arendt (London: Pimlico, 1999), 245–255.

Bosmans, Sigrid, and Heidi De Nijn. “Het Mechelse museumtraject. Krijtlijnen voor een nieuw museum,” FARO | tijdschrift over cultureel erfgoed, 7 (2014), 14–16.

Burnham, Rika, and Eliott Kai-Kee, Teaching in the Art Museum: Interpretation as Experience (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011).

Cayron, Fanny, and Delphine Steyaert. Made in Malines. Les statuettes malinoises ou poupées de Malines de 1500–1540: Étude matérielle et typologique. Scientia Artis (SCAR). Bruxelles: Institut Royal du Patrimoine, 2020.

Chapuis, Julien. “Early Netherlandish Painting: Shifting Perspectives,” in From Van Eyck to Bruegel. Early Netherlandish Painting in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ed. Maryan W. Ainsworth and Keith Christiansen (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), 3–21.

Classen, Constance. The Museum of the Senses. Experiencing Art and Collections (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017).

Eichberger, Dagmar. Leben mit Kunst, Wirken durch Kunst: Sammelwesen und Hofkunst unter Margarete von Österreich, Regentin der Niederlande (Turnhout: Brepols, 2002).

Eichberger, Dagmar, ed. Women of distinction: Margaret of York, Margaret of Austria (Leuven: Davidsfonds, 2005).

Eichberger, Dagmar, Philippe Lorentz, and Andreas Tacke, eds. The Artist between Court and City (1300–1600) (Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2017).

Elffers, Anna, and Emilie Sitzia. “Defining participation: practices in the dutch art world,” in Museum Participation : New Directions for Audience Collaboration, ed. Kayte McSweeney and Jen Kavanagh (Cambridge: MuseumsEtc, 2016), 39–67.

Erasmus, Desiderius. Een goddelijk festijn. Samenspraak. Transl. Jeanine De Landtsheer (Rotterdam: Ad. Donker, 2004).

Kristeller, Paul Oskar. “Humanism,” in The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy, ed. Charles B. Schmitt and Quentin Skinner (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 113–137.

McSweeney, Kayte, and Kavanagh, Jen. Museum Participation: New Directions for Audience Collaboration (Edinburgh, MuseumsEtc, 2016).

Museums Association, Museums change lives. https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-change-lives

Majid, Asifa, Seán G. Roberts, Ludy Cilissen, Karen Emmorey, Brenda Nicodemus, Lucinda O’Grady, Bencie Woll, et al. “Differential Coding of Perception in the World’s Languages,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 45 (6 November 2018), 11369–11376. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1720419115.

Neuville, Pat, and Ann Rowson-Love. Visitor-Centered Exhibitions and Edu-Curation in Art Museums (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017).

Simon, Nina. The Participatory Museum (Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0, 2010).

Vocht, Henry de, ed. Jerome De Busleyden, founder of the Louvain Collegium Trilingue: his life and writings (Turnhout: Brepols, 1950).

Wienen, Marijke. “Het museum als ontmoetingsplek,” in OKV special issue Museum Hof van Busleyden 56, no. 3 (Gent: Openbaar Kunstbezit Vlaanderen, 2018), 29–32.

Sherry R Arnstein devised the ‘ladder of participation’ that suggests there are eight levels of citizen participation, from ‘manipulation’ at the bottom of the ladder to ‘citizen control’ at the top. Arnstein, “A Ladder,” 216–224.

Sherry R Arnstein devised the ‘ladder of participation’ that suggests there are eight levels of citizen participation, from ‘manipulation’ at the bottom of the ladder to ‘citizen control’ at the top. Arnstein, “A Ladder,” 216–224.

[1] See also the initiative Farm of the World at http://farmoftheworld.nl, last accessed on 29 April 2020.

[2] The first workshop took place from 15–18 January 2019; the second workshop with PhD and graduate students was part of the Dutch Graduate School Onderzoeksschool Kunstgeschiedenis in context of the Materials & Materialiy in Art History Course, 14 March 2019. The Artechne team also partnered up with conservators of the Heritage Department of the University of Antwerp who organized the one-week ROOHTS Summer School on Burgundian Black at Antwerp, Belgium, 1–5 July 2019.

[3] On the archival research and the re-enactment workshops see the contributions of […] elsewhere in this volume.

[4] On the trade in colorants in the Burgundian–Habsburg Low Countries, see the essay by Jo Kirby elsewhere in this volume.

[5] See, for example, Majid et al., “Differential Coding of Perception.”

[6] Erasmus, Een goddelijk festijn.

[7] On Burgundian Mechelen, see Eichberger, Women.

[8] On the position of artists in urban and courtly contexts, see, for example, Eichberger et al., The Artist between Court and City.

[9] Eichberger, Leben.

[10] Cayron & Steyaert, Made in Malines.

[11] Kristeller, “Humanism.”

[12] Benjamin, “Theses,” 247.

[13] On the interest in early Netherlandish painting in the nineteenth century, see Chapuis, “Early Netherlandish Painting.”

[14] The Museum Project, as a process leading to the eventual realisation of Museum Hof van Busleyden, was described in various publications. See Bosmans and De Nijn, “Het Mechelse museumtraject.”

[15] Wienen, “Het museum als ontmoetingsplek.”

[16] In the FARO convention of 2005 heritage is defined as a group of resources inherited from the past which people identify, independently of ownership, as a reflection and expression on their constantly evolving values, beliefs, knowledge and traditions.

[17] Elffers and Sitzia, “Defining participation,” 43.

[18] The “Museums change lives” campaign supported by Museum Associations in the UK or the “Our Museums” program from the Paul Hamlyn Foundation are but a few of the many initiatives giving evidence to this change in attitude and museum’s perception, see: https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-change-lives or http://ourmuseum.org.uk/?welcome=1.