Phillip the Good is remembered for his lavish style, cultivating the appearance of a powerful prince in command of seemingly infinite resources. The carefully orchestrated self-presentation of Philip the Good at court and on the international stage of Europe’s royal rulers has outlived the Valois duke and shaped our imagination of premodern Burgundy. Contemporaries and historians have commented on the duke’s penchant for fashionable dress and pompous display, and speculated about his motives for favouring one colour above all others at the Burgundian court, black.[1] Chronicles and court records provide evidence of ducal expenses for fine fabrics and for the maintenance of a stately entourage, reflecting and augmenting the majesty of the Duke of Burgundy. Based on this archival evidence, Sophie Jolivet has shown how black came to dominate Philip the Good’s wardrobe over the course of his reign. Her study also gives us insights into the importance of chromatic politics and well-chosen clothing, cut or adapted to the nature of public encounters and occasions.[2] The archival evidence aligns surprisingly well with visual depictions of the duke and his entourage on panel, parchment, and paper.[3] The abundant miniature portraits testify to the duke’s taste for fashion and his active patronage of illuminated book production.[4] They are also manifestations of his success in creating a lasting impression of himself as a magnificent ruler, dressed for the occasion. In this essay I show how these Burgundian miniatures contributed to the compelling visuality of Philip the Good’s powerful ducal self-presentation in Burgundian black.

Reworking a variety of black pigments for manuscript illumination with Birgit Reissland and Jenny Boulboullé, Atelier Building Amsterdam. A film by Katrien Vanagt and Stefano Bertacchini, 2020 @Serafín Productions for ARTECHNE.

Burgundian Manuscript Culture

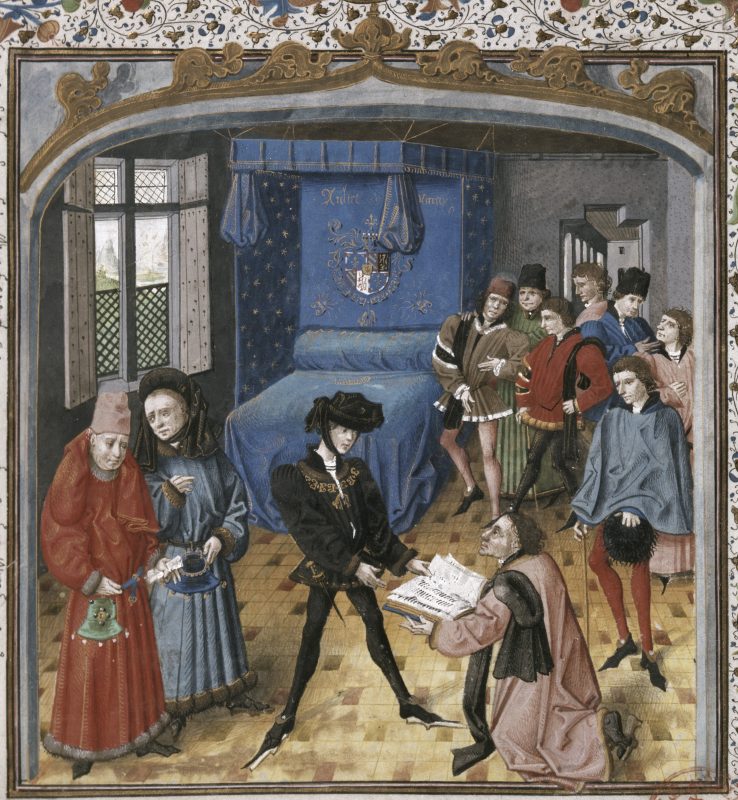

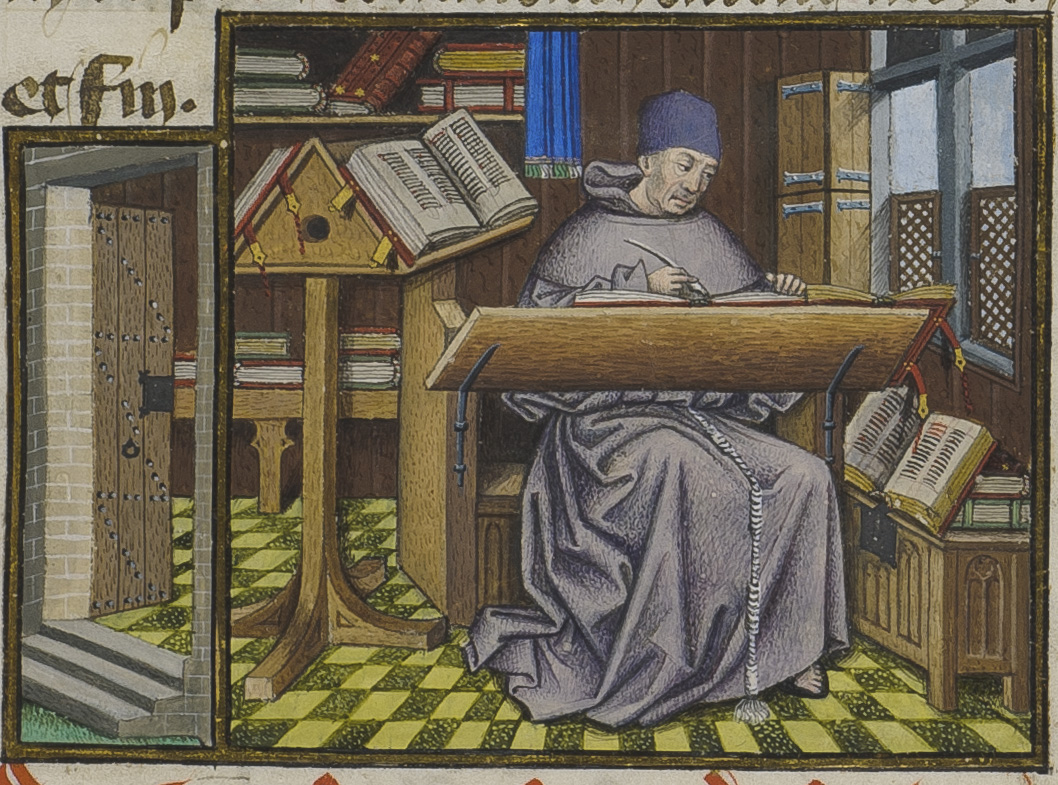

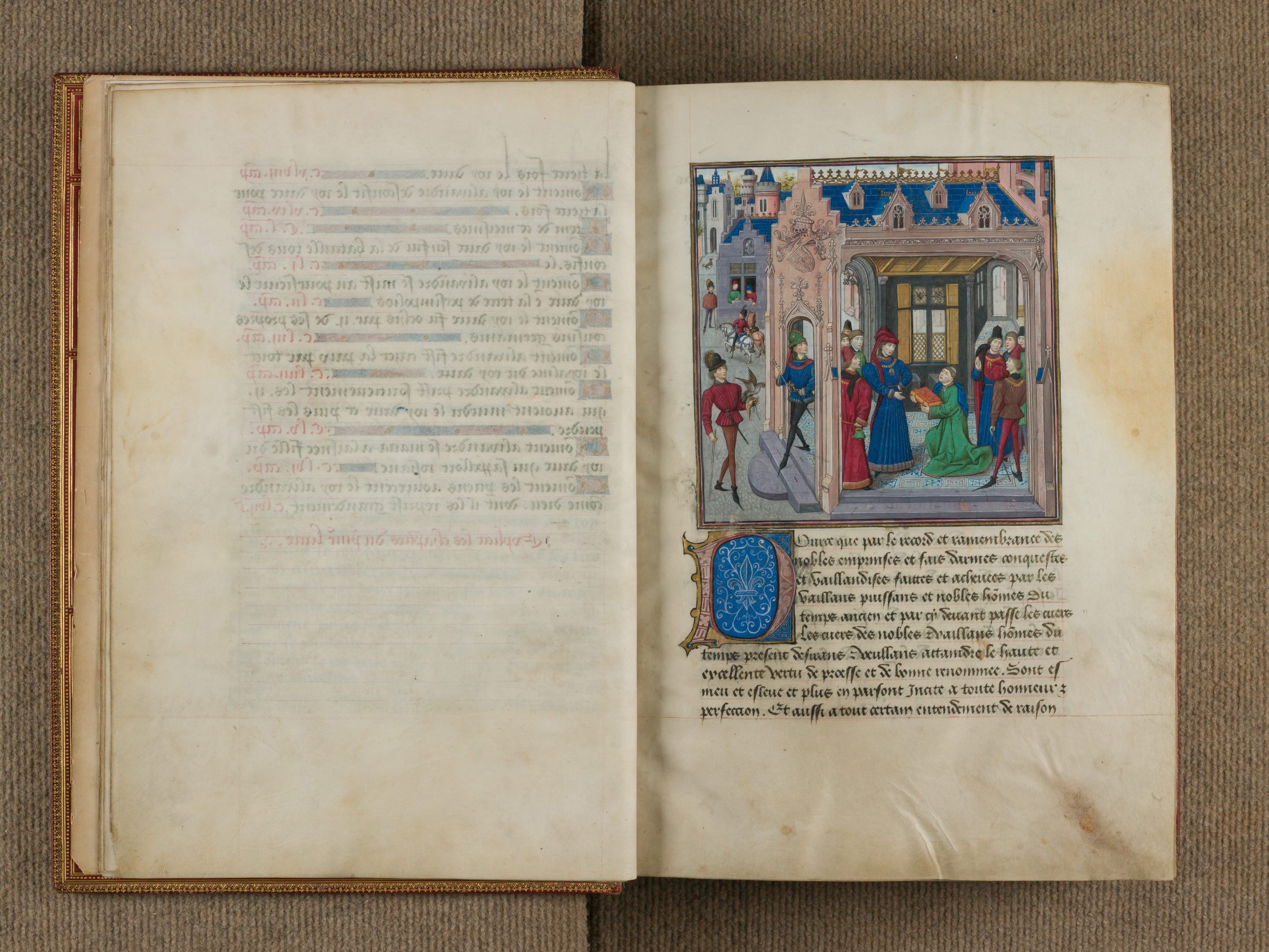

During the reign of Philip the Good, third Valois Duke of Burgundy, manuscript-making and the art of miniature painting reached unprecedented heights until these artforms and their political impact were superseded and marginalized by the rise of the printed book and print illustrations. The duke’s patronage provided an important impulse for the production of codices that belong today to some of the finest masterpieces of fifteenth-century European manuscript culture. Already in the Middle Ages, the Library of Burgundy (Librije), was widely valued for its precious and vast collection of manuscripts, illustrating the significance of the Librije in the glorification of the power of the dukes. Recent studies have also emphasized the role of Philip’s active patronage and manuscript production in the unification of a Burgundian ‘state’.[5] The beginnings of the Librije date back to Philip the Bold (1342-1404), first Duke of Burgundy from the House of Valois. Under the following dukes, the bibliophiles John the Fearless (1371-1419) and Philip the Good (1396-1467), the Librije grew into one of the most prestigious libraries of the western world.[6] At the time of the death of the last Valois Duke of Burgundy, Philip’s son Charles the Bold (1433-1477), the Librije counted almost a thousand volumes. Richly illuminated books were precious prestige objects and important instruments for image-building for the dukes of Burgundy: ‘Much like jewels’, as Till-Holger Borchert puts it, ‘the books satisfied the patron’s desire to comply with the concept of princely magnificence’.[7] Codices were luxurious portable commodities that accompanied the itinerant court. Produced in large folio formats, like the Chroniques de Hainaut (measurement binding 47.3 x 31.4 x 7.0cm) [Figure 1],[8] their size allowed for public or shared readings and viewings [Figure 2].[9] The illuminated book thus provided an important medium for controlled dissemination of ducal self-presentation in word and image. Recent scholarship of the active ducal patronage of manuscript culture has shown that the Valois dukes built a powerful narrative and established enduring iconography of their rulership over Burgundian dominions.[10]

Instruments of Ducal Propaganda

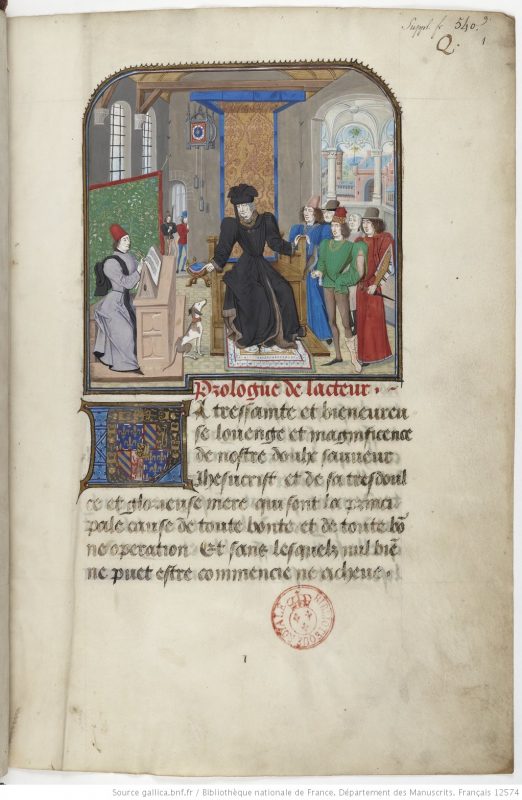

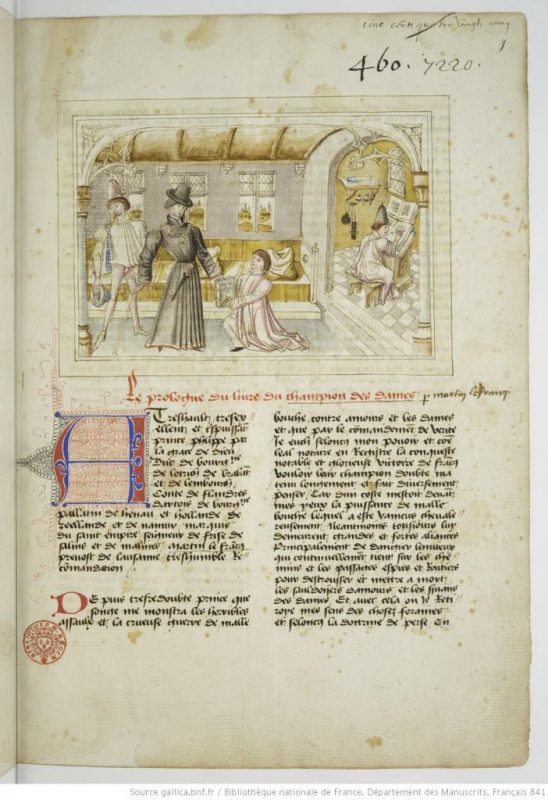

How did Flemish master illuminators co-shape the chromatic politics of the Duke of Burgundy and contribute to the enduring popularity of Burgundian black? To answer this question, I focus in this essay on miniature portraits commissioned by or for Philip the Good that show him dressed from top to toe in black. A striking number of such portraits dating to the fifteenth century have survived in Northern European manuscript collections. The most famous ones are found in three different manuscripts, all produced in the same period, ca. 1446-1448: the Chroniques de Hainaut (ms. 9242, fol. 1r, KBR, Brussels; Figure 1), the Roman de Girart de Roussillon (Cod. 2549 HAN MAG, fol. 6r, ÖNB, Vienna; Figure 3), and La geste ou histore du noble roy Alixandre, roy de Macedonne (hereafter Histoire d’Alexandre, ms. 9342, BNF, Paris, fol. 5r; Figure 4).

The frontispieces feature full-length portraits of Philip the Good and his entourage commemorating the moment that the illuminated books were presented to the duke. Many more miniature portraits of the black-dressed duke were produced during his lifetime and under the reign of his son Charles the Bold (see e.g., Figures 5a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j 1-3).[11]

The pictorial genre of the presentation miniature alludes to the chaîne opératoire of manuscript production — its cultural context, strategies of transmission, and forms of reception — by portraying the manuscript’s writer/scribe, the book itself when it is handed over to a patron, and its recipient: the patron/commissioner and/or intended owner of the artifact.[12] Book presentation scenes have a long history dating back to ancient times, but scholars have observed an increasing popularity of dedication scenes in the fourteenth and fifteenth-century manuscripts, in particular under the patronage of French and Burgundian rulers from the House of Valois.[13] Borchert, for instance, sees in the frontispiece of the Chroniques de Hainaut ‘a normative prototype’, setting the trend for ‘Burgundian dedication pages’.[14] Pascal Schandel distinguishes a novel Burgundian ‘sub-genre’ of presentation miniatures, dedicated to the patron who commissioned them, appearing at court during Philip’s active patronage of literary works and manuscript production. Schandel observes that these dedication scenes are almost all produced within the ducal territories under the strict supervision of the Duke of Burgundy. The frontispieces of the Chroniques de Hainaut and of Jean Wauquelin’s other two works [Figures 1,3,4], all produced in close vicinity to the center of ducal power, form an exemplary triad of this genre of Burgundian presentation scenes.[15] Scholars have described these miniatures and the literary works they adorn as ‘veritable instruments of propaganda’, and as ‘central components of [Philip’s] politics of splendour’.[16]

Picturing a Book in a Book

Looking more closely at the splendid presentation miniature, measuring 14.8 x 19.7cm inside the painted frame on a folio of 44 x 31.2cm, of the first volume of the Chroniques de Hainaut [Figure 1],[17] we see the painted figure of the black-dressed duke stand out sharply against the golden glow of richly decorated throne hangings. In front of him kneels a man dressed in subdued colours who presents him with a large codex. We can sense the book’s heavy weight, resting on the full length of the figure’s left arm. The richly decorated leather cover draws our gaze into the pictorial space, inviting us to take a closer look at the detailed rendering of the book cover. We can discern a decorative pattern of blind-tooling marks painted with darker brown brushstrokes onto the leather-bound cover and five decorative gilded bosses, protecting the bookbinding when opening the book. The leather straps that hold the voluminous codex together have gilded (brass?) fastenings. The locked book, a common motif in dedication scenes, alludes perhaps to the wealth of crafts knowledge embodied in these handmade artifacts, generally kept secret by their makers and guilds[18] (e.g., Figures 1, 3, 4, 5b, 5e, 5h). Yet precious illuminated books were certainly not only intended for private contemplation by their owners. The manuscript’s large format — much bigger than the codices depicted in the presentation miniatures of the Histoire d’Alexandre or the Girart Rouissillon — emphasizes not only its ceremonial function, but is also suggestive of a shared court culture of reading and of viewing these splendidly illuminated manuscripts together.[19] The wax remains found on its frontispiece call to mind past readers who closely examined the mastery of the miniature painter by candlelight.[20]

The illuminator of the Chroniques de Hainaut frontispiece depicted the medieval book in stunning detail as a well-crafted artifact: zooming in we can discern the two long-strap metal fastenings connected to twined strings that are attached to the leather binding.[21],[22] The gold-coloured decoration and rectangular confines of the book cover visually echo the gilded frame of the miniature painting. The play of framing — moving from the outer gilded frame that opens up the depth of the pictorial space to the gilded book cover that frames its hidden content — is evocative. Imagine hearing the metallic sound of the fitting when opening the weighty book cover, revealing the very presentation miniature we are looking at now. We would see again the black figure of the duke, again a miniscule book presented to him by a kneeling figure, we could discern its heavy gilded book cover, open it in our imagination to encounter the same image again and again. Hidden under the locked book covers opens an ever-retreating pictorial space, in which the imagery of the presentation miniature appears as an infinite regression.

Mise en Abyme

The motif of the presentation miniature calls to mind a mise en abyme, a French term for a pictorial strategy deriving from heraldry that refers to the presentation of a blazon in a blazon of arms, evoking a pictorial multiplication ad infinitum in the eye of the beholder.[23] The image-makers allude here perhaps to the potentially unlimited reproduction and circulation of miniature presentations in contemporary manuscript culture,[24] an effect that is exponentially intensified in our age of manuscript digitization. At the same time, the mise en abyme, literally ‘placing into the abyss’, directs the gaze of the viewer deeper and deeper into the past towards an imaginary, unreachable point of origin. This pictorial strategy chimes with political ambitions underpinning the commissions of the three illuminated texts, the Chroniques de Hainaut (Chronicles of Hainaut), the Histoire d’Alexandre (History of Alexander), and the Roman de Girart Rouissillon (romance of Girart Rouissillon) [Figure 1,3,4]. Put into prose by the Burgundian liberier[25] Wauquelin [Figure 6], this triad is part of Burgundian literary practices that sought to legitimize Philip’s reign and territorial expansions with legendary and historical narratives, tracing the Valois dukes’ ruling right over the Burgundian lands back to an imagined origin in ancient or mythical times. The Chroniques de Hainaut, a French translation of Jaques de Guise’s Latin Annales Hannoniae, purports a ducal claim to Trojan descent,[26] the Histoire d’Alexandre places the Great Duke’s own territorial expansion drift into a continuous line with the historical figure of Alexander the Great, a Macedonian king of mythic proportions.[27] Finally, Philip’s claims to an ancient kingdom of Burgundy are revived in Wauquelin’s version of the Roman de Girart Rouissillon for which he rewrote verse romances and historical materials into a prose that perpetuates the legend of Burgundy’s first ruler who was believed to have lived in the ninth century and appears in medieval chansons de geste, singing the praises of Charlemagne’s reign.[28] All three works were produced within a stunningly short time span, between 1446 and 1448. Wauquelin worked on these projects under the patronage of Philip the Good, except for the Histoire d’Alexandre that was originally commissioned by his son-in-law, John of Burgundy, in the 1440s, but soon reproduced in two luxurious illuminated copies for the Duke of Burgundy [Figure 4 and Figure 7].[29] The stylistic and iconographic similarities between the three frontispieces strengthen the impression that these three illuminated books were part of a larger political program of consolidation that the third Valois Duke of Burgundy intended to communicate in this crucial phase of his reign, a period that witnessed the incorporation of new domains in the Low Countries into the rising ‘state of Burgundy’.

As said above, the pictorial strategy of a mise en abyme, popular in medieval artistic production[30], does not only evoke a diachronic timeline directing our gaze back in time, it also alludes to the potential power of portable artifacts to serve as models for virtually endless pictorial and textual multiplications, at a time when Gutenberg’s semi-mechanical printing press was still in its embryonic stages. Illuminated book production flourished under Philip the Good’s active patronage and contributed to the creation, distribution, and circulation of carefully orchestrated ducal self-presentations in text and image. This high art of manuscript making constituted the last blossom of an ancient craft, just before it was replaced by letterpress printing, causing the professions of copying and illuminating manuscripts to disappear for good. Yet in the fifteenth century, these elaborate presentation miniatures still played an important role in creating the visual imagery of a Burgundian sovereign. Philip the Good raised one single colour above all, black. And it was these masters in illumination, working in watercolour on parchment, who created a lasting image of the ‘Great Duke and Great Lion’ painted from top to toe in Burgundian black.[31] Nonetheless, it would be reductive to describe the frontispieces featuring full-length portraits of Philip the Good with lifelike features and easily identifiable in his monochromatic appearance, as true to life translations or pictorial ‘recordings’ of a princely performance. Rather, miniature portraiture seems to have been part of an image-building strategy — designed from the outset to outlive Philip’s living presence — that could effectively convey the duke’s power and authority over the Burgundian lands ‘over here’ and ‘over there’.

The chromatic systematization of the ducal wardrobe, dating to the end of the 1430s,[32] was accompanied in the following decades by a growing interest in literary productions and the arts of bookmaking. Philip the Good’s conscious self-fashioning in black as ruler over the Burgundian lands and powerful prince on the European stage came with an active patronage of illuminated manuscript production that clearly connected Burgundian bibliophily with ducal politics.[33] Similarly, the distinct predominance of black in Philip’s appearance co-occurred with a decisive shift in political interests towards the north, a development that had set in with Burgundian expansions under the first Valois dukes of Burgundy, Philip the Bold (1342-1404), and John the Fearless (1371-1419), who was born and raised in the duchy of Burgundy, where he preferred to reside with his court in the city of Dijon, but contributed to the transformation of the dispersed Burgundian lands into a centralized ‘state’ when he moved his council to Ghent.[34] His son Philip the Good had spent much of his youth in Flanders, where he lived, from the age of fifteen until his twenty-third year, in the city of Ghent.[35] Philip the Good, whose ‘great deeds and glorious adventures’ endured in the hands of the court chronicler George Chastellain, definitely turned his gaze northwards with an unconcealed ambition to expand his territories in the Low Countries.[36] This shift in point of perspective as ruler over the Burgundian lands is manifest in the fifteenth-century expression ‘les pays de par deça‘ that Philip used to distinguish his northern territories from his ‘lands over there’ (‘pays de par delà‘), the duchies of Burgundy and Franche-Comté, situated in modern-day Southern France.[37] Philip preferred to reside with his court ‘over here’ in the Low Countries where he invested in commercial relations with Brabant and Hainaut that came under Burgundian reign in the 1430s, and maintained lucrative connections with Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian merchants with direct access to global trade networks.

Framing Political Ambitions and Aspirations

Graeme Small lays a link between significant territorial expansion under the reign of Philip the Good and some remarkable acquisitions for the ducal library. By the mid-1440s Philip had brought Namur, Holland, Hainaut, Zeeland, Brabant, and Luxembourg under Burgundian rule. The same decade saw the completion of several historiographical projects telling the histories of recently annexed dominions among which the French translation of the chronicles of Hainaut, produced in Mons, a city in Hainaut where Wauquelin had his studio under the patronage of the Duke of Burgundy.[38] Interestingly we can witness in the same period a decisive chromatic shift in the ducal wardrobe: the ducal records document a rapid decline in purchases of dark tinted wools, (draps de brunette), and an increase in the consumption of black woolen cloth (drap de laine noir) after 1440, while the Burgundian court also maintained a clear preference for black silks.[39]

Zooming out from the detailed depiction of the closed codex in the frontispiece of the Chroniques de Hainaut, we can appreciate the carefully designed layout of the folio as a whole [Figure 1; see also the digitized manuscript, image 11]. The mise en page with its graphic elements — two text columns on the lower page written in batârde — also known as lettre de bourguignonne — in the steady hand of a professional scribe[40], and broad decorative margins displaying heraldic emblems and delicately drawn floral patterns, accentuates the theatrical effect of the miniature painting. The presentation scene is staged in a court chamber with checkered floor tiles and a baldachin construction that draws our gaze into the depth of the pictorial space towards a window at the back. The painted margins that frame the text and image stand out for their delicate, colourful renderings. The painted blazons have been associated with the court painter, Hue de Boulogne (before 1400-1451) and his son Jean, who were responsible for the execution of painted panels for the Chapters of the knightly Order of the Golden Fleece, established by Philip the Good in 1430[41] and the ephemeral artworks used for courtly events and festivities, including flags and banners, but also knightly surcoats (la cotte d’arme) worn on top of suits of armor, the only ducal garment commissioned from court painters.[42] Obviously, modern day disciplinary distinctions in the arts between painting, heraldry, textile, decorative and performative arts were much more fluid then.

The heraldic bearings that appear here in the margins testify to Philip’s state-building aspirations and his aim to unify his southern and northern dominions under Burgundian rule: on the left are the duchies of (ancient) Burgundy, Lorraine, Brabant, and Limburg, followed by the counties of Flanders, Artois, and Franche-Comté. On the right are the coats of arms of Hainaut, Holland, Namur, Friesland, Charlerois, Boulognes, and Malines. The coats of arms are represented in hierarchic order, strictly following the chronology of the titular listing written in the second column underneath the miniature: ‘Monsieur philippe par la grasce de dieu. Duc de bourgoigne. de lothringe. de braiba[n]t et de lembourc. conte de flandres. dartois. de bourgoigne. palatin de hainau. de hollande. de zelande et de namur. marquis de saint empire. Seigneur de frize. de salins et de malines’.[43] Visually the heraldic emblems are devoid of any hierarchical or titular distinctions. Noticeably, all dominions represented by their coat of arms are painted in a unified style that echoes the political ambitions of the Duke of Burgundy to unite these territories into a — never realized — ‘Burgundian state’.[44] The much-desired Frisian Crown also remains out of Philip’s reach, despite his lordship of Friesland and his keen and sustained interest in the kingdom of Frisia.[45] Some of the heraldic bearings visible in the margins are incorporated into the ducal emblem on top of the folio, at the center of the marginal decorations. Philip’s coat of arms transforms during his reign in accordance with territorial annexations and titular claims, eventually including all of the here-listed duchies, counties, and seignories. The golden helmet painted enface had traditionally been preserved for royal heraldry, just like the regal expression ‘by the grace of God’ (‘par la grasce de dieu‘) preceding Philip’s titles in the text, that was used in France — until then — exclusively by the French king.[46] Both are forthright expressions of Philip’s claim to royal authority, purportedly bestowed on the Valois duke directly by divine right. Suggesting the key role of Flanders in the ducal vision of a Burgundian state, Flanders’ emblem of the black rampant lion on a golden ground is placed at the very heart of the ducal coat of arms: Flanders was the center of Burgundian power and Burgundian art production, home to northern Europe’s best black dyers and makers of the famous black broadcloth. The hartschild[47] bearing Flanders heraldry belongs to one of pre-modern Europe’s most urbanized and prosperous regions, with a well-developed textile industry and an important port located at the crossroads of northern and southern trade: Bruges, one of the preferred residences of Philip`s itinerant court, and the city where he celebrated the marriage to his third wife, Isabella of Portugal, in 1430, and where he died in 1467.[48] Produced towards the end of the 1440s, the three presentation miniatures commissioned by and for Philip the Good follow a period of sustained effort to consolidate and expand the ducal authority in the Burgundian Low Countries, in particular in the cities of Flanders and adjacent regions, connected by the Schelde river, where well-organized craft guilds had given rise to an urban middle class with political ambitions.[49]

Image-Building in Artists’ Hands

The presentation miniature’s political significance has received at least as much attention as its outstanding painterly quality. The frontispiece of the Chroniques de Hainaut has been ascribed to Rogier van der Weyden (1399 – 1464) and workshop, famous for the visual realism he achieved in his oil paintings.[50] Scholars have emphasized van der Weyden’s important role in creating a lasting image of the duke, shaping the conception of the Burgundian ruler at court and for future generations.[51] In fact, most of the surviving ducal portraits have been ascribed to van der Weyden or his workshop, including a much-copied lost painting of Philip the Good with black chaperone [Figure 8a-c] and another portrait showing him bareheaded that survives in the collections of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA) and the Royal Palace in Madrid [Figure 8c].[52] The attribution of the frontispiece seems in line with the ‘image-building’ role that has been ascribed to the artist and his workshop.

More iconic portraits depicting Burgundy’s mightiest men in sumptuous black dress came out of van der Weyden’s workshop, such as a full-length rendering of the duke’s right hand, Nicolas Rolin, chancellor of Burgundy (1376*, 1422-1461) on the outer panel of the large Last Judgement altarpiece at the Hotel Dieu of Beaune.[53] With closed wings, the portraits of the patrons come into sight: Rolin is depicted in a fur-lined black. In a similar fashion as in the presentation miniature of the Chroniques de Hainaut, his dark figure stands out sharply against a gold-coloured background, here made of applied brocade imitating the rich sheen of cloths of estate hangings [Figures 10 and 1].[54] We can observe a remarkable resemblance between the lifelike facial features of the duke, Rolin and Bishop Chevrot painted on panel and parchment [Figure 12].[55]

Art historians have traced the visual impact of van der Weyden’s paintings.[56] Portraits originating in the artist’s workshop, like the lost portrait of Philip the Good, became widely known and saw many copies [Figure 8a-c; other copies survived e.g. in the Royal Collection Trust, UK, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Austria].

It remains remarkable, though, that the frontispiece of the Chroniques de Hainaut is the only book illumination painted in watercolour that has been ascribed to Rogier van der Weyden, who is mainly known for his works in oil on panel.[57] Recent studies on artisanal networks and workshop practices in fifteenth-century Flanders have shown that it was not uncommon for painters and miniaturists specializing in evermore sophisticated book illustrations to apprentice in the same workshops, despite the fact that the art of book making had its own distinct professions, some with their own guilds, such as scribes, rubicators, paper and parchment makers, book binders, and illuminators specialized in initials, marginal illuminations, and more. Scholars have shown that painters in van der Weyden’s circle took on commissions for miniatures or to train miniaturists in their workshops.[58] In van der Weyden’s birthplace, Doornik/Tournai — an important artistic center in close contact with the city of Ghent with which it was directly connected through the river Schelde — illuminators, painters, and glass artists were members of the same guild.[59] This was not unusual: miniaturists were also permitted into the painters guilds in Brussels where van der Weyden moved in the 1430s.[60] Tellingly, van der Weyden’s workshop in Brussels was located close to the ducal palace.

Scholars have proposed that van der Weyden kept several drawing models of the presentation miniature in his workshop, which could perhaps explain the existence of so many roughly contemporary copies and variations of this motif [Figure 1, 3, 4, 5b laterally reversed and 13].[61]

Such carefully orchestrated models could have served as a basis for a standard depiction of the duke and his court and might be the departure point of closely related miniatures. Whether such drawing models also might have included instructions for colouring is an open question, as these two luxurious manuscript copies of the Chroniques de Hainaut [Figure 13, ms 9043] and the Histoire d’Alexandre [Figure 7, ms dutuit 456] with frontispieces in differing colour schemes show.[62]

More recently it has been suggested that van der Weyden’s neighbor, the Parisian miniaturist Dreux Jehan (died 1466/67?), based in Brussels between 1447 and 1454, could have been responsible for the presentation miniature in the Roman de Girart Rouissillon, which obviously correlates to the group of presentation miniatures [Figure 3].[63] Jehan worked in service of Philip the Good and the Burgundian court and his name appears in the ducal records in 1448, the attributed date of the manuscript.[64] Recent scholarship favors attributions to workshops rather than to individual hands, as archival evidence suggests that Jehan, as so many others, hired artisans for his work on ducal commissions.[65] Jehan belonged to the same brotherhood as van der Weyden[66] and it is not unlikely that he could have had direct access to the ‘models’ used in his neighbour’s workshop.[67]

The presentation scenes that portray the duke dressed for the occasion from top to toe in black [Figures 1, 3, and 4] have been described as ‘a political act’ and ‘political manifesto’.[68] The texts they adorn evidently derive from the hands of one person, the ducal librier Wauquelin who lived and worked in Mons, a city in the county of Hainaut that together with Holland came under Burgundian reign in 1433. But the illuminations were commissioned from different workshops, supporting the suggestion that the duke favoured a form of patronage that allowed him to recruit the finest artisans active in his extended dominions and to consolidate his reign in his new territories with local commissions.[69] Exemplifying this deliberate choice of leading artists is the painter of the presentation miniature of the Histoire d’Alexandre [Figure 4] who has been identified as Willem Vrelant (died c. 1481/1482), a master miniaturist born in the northern Netherlands, close to Utrecht. His name appears among the records of artisans involved in book production that belonged to the same guild in Bruges, one of the artistic centers of what has become known as the ‘Burgundian style’.[70]

It is possible that the ducal librier Wauquelin as well as the duke himself played an active role not only in the selection of artists, but also in the configuration of the illuminations in the commissioned manuscripts, underlining their propagandistic function.[71] Such a political reading of Burgundian miniatures has in particular been offered for the three frontispieces portraying Burgundy’s ruling elite in a contemporary courtly context. Schandel convincingly showed, for example, how the pictorial program of the frontispiece of the Chroniques de Hainaut aligns with the ordination of 1446, that was established by Philip and redefined the ruling body over the Burgundian dominions.[72] Costume- and art- historians have similarly emphasized the importance of these visual sources for the study of contemporary dress fashionable at the Burgundian court. A recent analysis of expenses for textiles and clothing in the extraordinarily well-documented ducal accounts has confirmed a certain documentary value for these painterly impressions of Burgundian court life, and especially for the black ducal dress in the frontispiece of the Chroniques de Hainaut.[73] Noticeably, a political reading of Burgundian miniature portraiture echoes the findings of Jolivet, who has shown that Philip’s conspicuous taste for black dress developed only fully and systematically in the 1440s when the Duke of Burgundy reached the height of his power and long after he had buried his father in 1419, questioning an intentional choice of black apparel as a statement of mourning. Jolivet argues elsewhere in this volume that Philip’s deliberate preference for finest black fabrics was a distinct expression of Burgundian chromatic politics, calling to mind the visual image of the Black Lion that adorns the coat of arms of Flanders. Our visual analysis confirms the political significance of the colour black, as it appears in the presentation miniature in the ducal dress and in the emblematic image of the fierce lion [Figure 1 and 14].

In line with Jolivet, we argue that black is used here on parchment to create a compelling political iconography of the ruler over the Burgundian lands, conflating the iconographies of the powerful Duke of Burgundy, the rich cities of Flanders, and the tradition of chivalry.[74] While ephemeral art forms of courtly splendours, including luxurious textiles and sumptuous dresses and costumes, central to the enactment of ducal magnificence and authority, have scarcely survived, we can still admire ‘medializations’ of Burgundy’s ‘Spektakelkultur’ in contemporary manuscript culture.[75] The surviving texts and images were instrumental in enacting princely power and in the creation of political iconographies and imagery that persisted and circulated in different media. Miniature portraiture can therefore not only be read as reflecting court realities or painterly renderings of ‘real’ ducal self-performances in Burgundian black. Illuminators not only pictured Burgundy’s politically motivated event culture, they also actively gave shape to the self-image of a Burgundian prince. The duke’s taste for exclusively black dress developed simultaneously with the rise in miniature portraiture at the Burgundian court after 1430. The compelling visuality of the black-dressed prince in miniature portraiture testifies perhaps to a highly cultivated pictorial awareness at the Burgundian court — similar to what people might call today a conspicuously bildbewusst, ‘photogenic’ or ‘instagrammable’ outfit. Jennifer M. Scarce made a similar observation about the ‘obsessively image-conscious’ Arabic courts ‘where colour-coding was a significant marker in the hierarchy of dress,’ reminding us of the prestige of black under the Abbasid Caliphate (c. 750-1258) when the colour was meant to be worn exclusively by the upper echelons in Baghdad, an important crossroad on the Silk Road networks and the center of the indigo trade in the Islamic medieval period.[76]

Philip’s chromatic preference for black attire was perhaps motivated by an astute aesthetic awareness for black as a powerful and effective image-making strategy to create a more enduring political imagery on parchment, paper, and panel. The many surviving ‘copies’ featuring a readily recognizable black-dressed duke that circulated in the flourishing visual arts under Burgundian reign might prove this point of a deliberate chromatic propaganda strategy across a variety of media. This pattern suggests that the commissioned panel painters and miniaturists mastered the art of black colouring to a degree that would suit his majesty, and could match the then highly developed arts of black dyers and textile makers.

Chromatic Politics

The fifteenth century witnessed the heyday of illumination in the Burgundian Netherlands, with manuscripts of unprecedented artistry and chromatic refinement. The colour knowledge assembled by illuminators over centuries reached a pinnacle at that time in northern Europe, exemplified in iconic works such as the presentation miniature of the Chroniques de Hainaut [Figure 1].

The pictorial space of this frontispiece is populated by 14 men, most of them dressed in lavishly coloured court costumes and some with remarkably life-like facial features. The miniature has been described as a veritable ‘portrait gallery’ allowing the viewer to identify Philip the Good amid the members of his princely council.[77] On the right side of the folio, the duke and his son are flanked by eight knights of the Golden Fleece, a group that represents Burgundy’s aristocratic elite and military strength. On the left side of the folio, we can see three persons lined up next to the duke. They have been identified from right to left as Nicolas Rolin, first chancellor, keeper of the ducal seals, and head of the Burgundian council in the absence of the duke, Jean Chevrot, Bishop of Doornik/Tournai, with similar administrative powers, who presided over the ducal council in the absence of Rolin, and the third figure on the far left side of the folio more tentatively as Guy Guilbaut, the ducal treasurer.[78] This triad of political, religious, and financial powers, form together with the duke the ruling body of Burgundy. [79] Conventionally, the kneeling figure presenting the codex would have been the writer himself — in this case Wauquelin — but others have argued that this is a portrait of the initiator of this translation project, Simon Nockart, native to Mons, ducal councilor, and local bailiff from Hainaut, which seems more consistent with the miniature’s political program.[80] Schandel has pointed out that the kneeling figure is clearly distinguishable by colour and dress from the group of knights behind him: the colour of his much longer dress looks by comparison bland and plain, lacking the chromatic vibrancy, pronounced decorative folds, and rich decorative patterns of the courtly garments.[81] Despite this observation, colour analysis has played so far only a marginal role in the political interpretation of the miniature. Buren-Hagopan underlines, for example, only the compositional and pleasing function of colour to distinguish and flatter the portrayed persons.[82] Curiously, scholars have hardly commented in their visual analyses of the frontispiece on the duke’s distinct appearance that stands in stark contrast with the colourful attires of the other courtiers. This strikes us as odd in light of recent research into the political significance of Philip’s pronounced preference for black dress and fifteenth-century chromatic politics more generally.[83] Moreover, material technical analyses of miniatures in illuminated manuscripts are still scarce in comparison with oil painting examinations,[84] but selected miniatures of the Chroniques de Hainaut, including the presentation scene, have been subject to laboratory examinations which provide further insights into the use of colour in Burgundian miniature painting.[85]

Non-destructive analytical techniques have been applied to the attires of Rolin, Chevrot and the duke to identify the colourants used by the illuminator.[86] The vital role and the powerful status of these Burgundian administrators were — as it were — clearly colour-coded for the contemporary viewer: right next to the duke, we see Rolin in a rich blue robe trimmed with what looks like the fur of sable, painted with such mastery that we can virtually feel its velvety fabric and furry cuffs.[87] Rolin is here literally depicted in his role as the right hand of the Duke of Burgundy, leaning on the right armrest of the ducal throne. The black chaperone Rolin is wearing echoes the headwear of the duke in form and colour, thus marking the close links between the chancellor, head of the Great Council, and the duke himself, head of the embryonic Burgundian state.[88] As head of finance, Rolin’s access to the riches of the ducal lands is reflected in the colour of his robe: the vibrant blue of the robe that has so brilliantly survived the ravages of time was likely achieved with (a top layer of) one of the most expensive materials used by artists, ultramarine pigment made from the semi-precious stone Lapis Lazuli that was imported into fifteenth-century Europe from overseas.[89] The rich colour of Rolin’s blue robe contrasts with the much paler blue of the robe of the kneeling clerk, painted with the less expensive pigments, azurite and ultramarine ash.[90] The latter is a lower-quality byproduct from the costly and labourious process for the production of ultramarine.[91]

To the period’s eye, the masterful rendering of such luxurious garments must have been striking. The precious painter’s materials contribute to a visual realism that echoes the luxury of the depicted garments: brilliantly blue dyed textiles were produced with a costly and labour-intensive vat dye technology (see Ortega Saez’ and Cattersel’s essay elsewhere in Burgundian Black).[92] The stunning blues evoke the riches from trade with distant lands on the other side of the ocean.[93] An increasing availability of imported indigo (Indigofera) with higher colourant concentrations than indigenous woad plants (Isatis tinctoria) made it possible for blue dyers, located in Flanders’ textile centers with direct access to trading ports, to attain high-quality intense blue colours with woad-indigo vats. The intensifying indigo trade soon resulted in a much-studied early form of mercantile protectionism attempting to defend the European woad industry against the rising global sea trade in indigo from plants native to Africa, Asia, and South America.[94] The brilliant blues, used here in a secular context, continue to evoke medieval iconographies that exploit the materiality of colours to convey religious meaning: the most precious artists’ materials, such as gold and ultramarine, were used for holy figures to render aureoles of saints and to depict the divine robes of Holy Mary, painted traditionally in the most brilliant and finest blues.

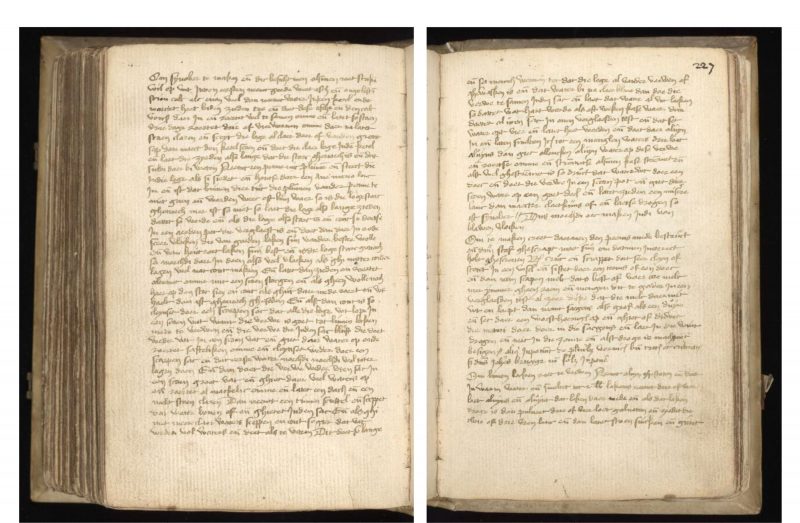

A similar argument can be made for the vivid reds used for the clerical dress of Chevrot that evoke the opulence of the most luxurious red fabrics (‘drap escarlattes’), traditionally worn by the leading dignitaries of the Christian Church.[95] Up into the late middle ages, these scarlet reds were dyed with a precious colourant harvested from insects (Kermes vermilio, Porphyrophora polonica L., Porphyrophora hameli) found in certain parts of central and eastern Europe, and Asia. The costly dyestuff reached Flanders’ centers of textile production through well-established trading routes until — at the end of the fifteenth and in the sixteenth century — the rise of the cochineal trade set in with the Iberian expansion into Central and South America where a different species of insect (Dactylopius coccus) with higher colour concentrations was found.[96] Presence of mercury in the painted red robes of Chevrot points towards the use of the natural mineral pigment cinnabar (mercury(II)sulfide, also known as vermilion), yet the analytic tools that were used are unable to detect traces of less lightfast organic lakes. We cannot exclude the possibility that the miniaturist may have enhanced the visual realism of his textile renderings by applying a thin transparent red paint layer, perhaps now faded, that is derived from the same red colourant used for red-dyeing the luxurious garments here depicted.[97] Organic red dyes and lakes can be made with colourant extractions from scarlet-dyed cloth shearings that painters used for thin top layers for shading or to create depth and brilliance.[98] The procedure is described in a manuscript in the collections of the Wellcome Library in London (MS 517), comprising a late fifteenth-century miscellaneous collection of diverse secrets in Middle Dutch, including art technological recipes. The handwritten recipe for preparing a red pigment ‘om synober te maken‘ provides instructions on how to extract a red colourant from wool shearings with a strong lye [Figure 15a and 15b]:

In an eighteenth-century vellum binding over wooden boards, measurements ca. 21,5 x 14,5 cm.

And when the lye is strong and cold, you put it into an earthen pot that is glazed, and you put in there the red shearings of good broadcloth (laken) that is (made) from the best wool, and the one of red wood broadcloth is best.[99]

The recipe describes an extraction process that yields a ‘verwe‘ as a by-product that can be used to dye linen red, and it gives instructions on how the remaining dyestuff can further be processed into a red lake pigment for painting. The recipe is sandwiched between instructions for illuminators, including paint preparations, instructions for gilding and lettering, and a set of textile dye recipes for red, blue, and yellow linen, illustrating the entangled transmission of illuminators’ and dyers’ colour knowledge.

Damasks, Velvets and Brocades

The black-dressed figure of the Duke of Burgundy stands out sharply against the light and shimmering background and the colourful costumes of his entourage; only one other knight is depicted in a black coat[100]. On the right and left sides, the persons are grouped together with overlapping contours, while the duke is depicted between the two groups in isolation. The painter singularized the ducal figure also chromatically: he is the only one dressed from top to toe in virtually one colour, visually echoing the ducal motto ‘I will have no other’ (‘Aultre narey’) that is written above his head, where it is set in unison with his armorial bearings in the mid-center of the gilded framing. The voluminous chaperon that had developed in the first half of the fifteenth century from an attached hood into an elegant independent head cover had been enlarged in the final painting, as studies of the underdrawing have shown.[101] This makes the duke appear slightly taller than everyone else. Philip’s exalted position here is accentuated by a lustrous green baldachin with a decorative golden edging. The decorative patterns of the throne cloth set off the duke’s almost monochrome appearance and the sharply delineated contours of his fashionable dress. The Duke of Burgundy is literally framed by Europe’s rich fabrics, produced with increasingly elaborate and sophisticated weaving techniques ‘to exploit sheer luxury for its own sake’: the fine brush of the miniaturist evokes on parchment the subtle sheen of the most costly textiles available at the time, including gold-coloured brocades and the elaboratively woven tone-on-tone patterns of shiny damasks and velvets.[102] Brocade can denote any kind of patterned fabric, but technically it refers to textiles with a supplementary pattern weave, often made with precious metal threads applied to the ground weave of the textile. Applied brocade imitations are abundant in pre-modern panel paintings.[103] Damasks were created with a weaving technique that could be used for wools, silks, and linen. The intricate weave structure with opposing warp and weft faces of damasked fabrics allows for subtle patterns brought out by the play of light on the surface texture of the textile.[104] Velvets were appreciated for their sumptuous appearance, created with a lush and dense surface pile of raised, cut or uncut loops, a weaving technique that enhances the textile’s depth of colour.[105] Often, woven-in elaborate monochromatic tone-on-tone patterns could be created with both techniques. Flanders master painters, and van der Weyden in particular, were famous for their renderings of fine fabrics and their luxuriant textures.

A recurrent contemporary textile motif found on the painted drapes and dresses in the frontispiece of the Chroniques de Hainaut and on textiles in Netherlandish panel paintings from van der Weyden’s workshop, are the decorative pomegranate patterns. X-radiographs have revealed elegant damaged pomegranate designs on the exterior side of the wings of van der Weyden’s Last Judgement altarpiece.[106] The applied brocades form the background of the earlier mentioned portrait of Rolin, creating a compelling contrast between Rolin’s black-dressed figure against the golden sheen of brocaded cloths of state, echoing the visual effect that is achieved in the presentation miniature, with the elegantly patterned throne hangings featuring a similar pomegranate pattern [Figure 10 and 11].

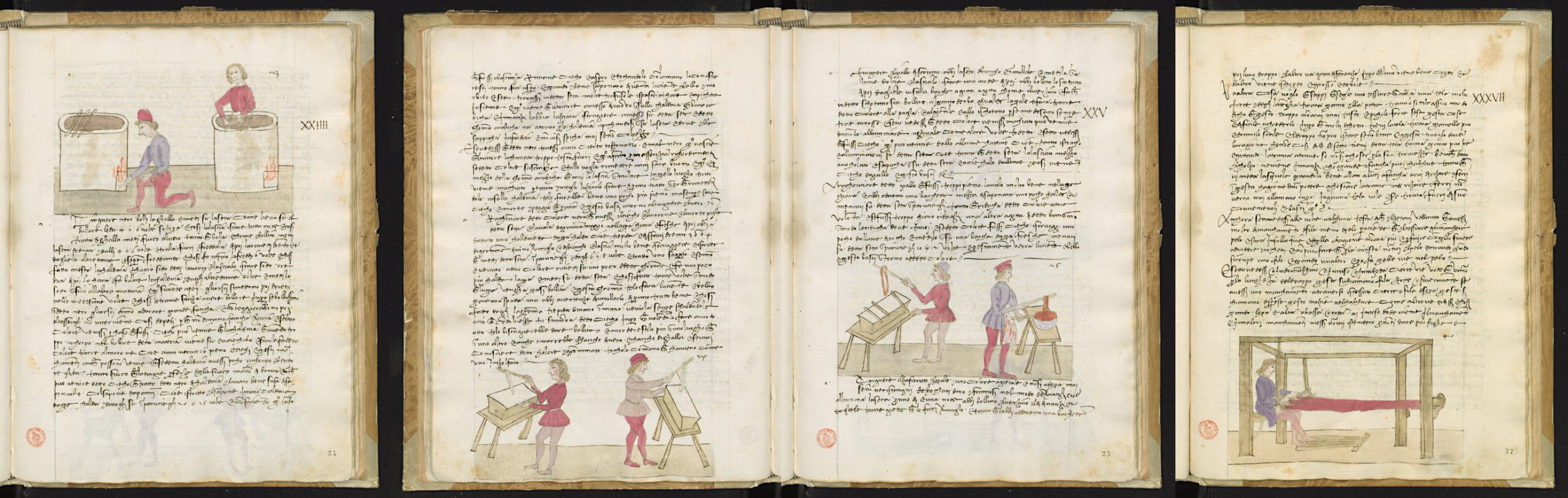

Such luxury textile designs became fashionable at European courts, precisely at the time this miniature was produced, in the mid-fifteenth century. The pomegranate design, a generic term for cusped or lobed forms with undulating stems often accompanied by elaborate foliate or floral decorations, came to predominate European textile designs after about 1430.[107] The design can feature pomegranates, pineapples, or visually kindred plant forms native to the European continent like thistles, pine cones, and artichokes, all motifs that likely derived from older lotus and palmette patterns.[108] An early mention of a pinecone pattern can be found in an Italian fifteenth-century handwritten manual devoted to the art of silk making and dying, that includes detailed instructions for black dyeing silks with illustrations of silk dye procedures and a coloured drawing of a simple weaving loom [Figure 16a – d].[109]

Pomegranate designs — the ‘chief textile motif of the fifteenth century’[110] — have a rich history of religious and secular connotations.[111] These designs, as Anna Muthesius explains, ‘exuded an aura of magnificence’ that was amplified by ever more elaborate weaves, including velvet techniques with diverse cut-pile effects and rich brocading.[112] It remains popular for public royal performances today, as can be seen in this video recording from the annual press conference with the Dutch king and queen on the day that the financial budgets for 2020 were revealed during the king’s yearly speech from the throne (troonrede).

Figure 17: Video of the annual throne speech (Troonrede op Prinsjesdag), King Willem-Alexander and Queen Maxima of The Netherlands, 15 September 2020, Sint James Church, The Hague, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/prinsjesdag-traditie-en-ceremonie/fotos-en-videos/video-troonrede-2020

Brocade, damask, and velvet techniques, all evoked here by the illuminator’s brush, had travelled to Europe from Asia and the Middle East together with exotic vegetal patterns like the palmette and pomegranate motifs of Byzantine origin.[113] The prince in Burgundian black presented himself as a center of gravity in a global trade network in colourful luxury goods. The opulent display of wealth in the presentation miniature served not only inner political ends but breathes also the ambitions of a ‘would-be crusader’ whose appropriation and domestication of foreign artistic innovations reflects the duke’s taste for religious — and economic — expansions into the East.[114]

As heir to the titles and domains of his father, the future position of the young Charles is emphasized visually: the colours and fashionable pomegranate design of his luxurious upper garment echo the colours and brocaded patterns of the throne drapes, foreshadowing the moment that the son will take the place of his father under the canopy. Charles’ pourpoint, tightly-fitted at the waist, and the heavy necklace align him with the duke and the other knights at his left, all members of the Order of the Golden Fleece, founded by Philip the Good in the 1430s. The outer form of a multi-lobed rosette visible on the arm of Charles the Bold is similar to the contours of the applied brocades behind van der Weyden’s Virgin with child, today at the Kunsthistorisch Museum in Vienna. It has recently been suggested that the light pinkish colours of the cloth of honor and of the dress of the future Charles the Bold in the miniature have faded and might have been much richer and darker reds, applied with organic red lakes.[115] If this was the case, the resemblance between the painterly imitation of a large patterned brocaded drapery as the backdrop to van der Weyden’s small Virgin with child panel would have been rather striking [Figure 18 and Figure 19].

Hardly visible in printed reproductions, but discernable when zooming in on the digitized folio and upon close examination, is a decorative pattern in the black attire of the Duke of Burgundy.[116] The colour black had surpassed precious reds in fifteenth-century Flemish luxury woolens, as John Munro observes.[117] Moreover, the subtle display of ducal splendours in Burgundian black was a remarkably effective pictorial strategy. This becomes apparent when we compare the triad of presentation miniatures in Wacquelin’s works with variations in other manuscripts. Jean Hennecart, another miniaturist who worked in service of the Burgundian dukes, deviated, for example, in two miniatures — both dated to 1468-1470 and modelled upon the Chroniques de Hainaut frontispiece — from the stringent colour contrast between the monochromatic ducal figure and the colourful and intricately patterned entourage and background.[118] Instead, Hennecart portrays the central figure in rich gold, brocaded reddish clothing that blends in with similar patterned and coloured throne hangings [Figure 20] or is set against contrasting green and gold ones [Figure 21].

In both cases, this increase in display of brightly coloured and patterned dress comes with a loss of compositional clarity. The same is true for miniature portraiture of Philip’s son, the ‘clothes-conscious’ Charles the Bold.[119] Margaret Scott has noted that ‘the general level of ostentation in dress increased dramatically under the dukedom of Charles the Bold’.[120] But she also points out, though, that on ‘the whole . . . manuscripts fail to convey the full splendor, not to say ostentation, of Charles’s clothing, and they give very few signs of the games that he played through clothing in order to manipulate his status’; with regard to miniature portraits of the last Valois duke, Charles the Bold, she observes that artists gave preference to the use of ‘a single strong colour in the dress to help Charles to stand out from the immediate surroundings’. Scott brings to attention that art in these cases did not imitate life; instead she proposes that ‘it may simply be the case that artists shied away from the potential aesthetic mess of setting the duke, clad in patterned cloth of gold, in front of patterned hanging’.[121] Her analysis supports our hypothesis that Charles’s father, Philip the Good, developed a strong preference for a monochromatic but no less opulent and sophisticated appearance in Burgundian black, because this colour set against richly patterned backgrounds proved to be a strong ally on paper, parchment, and panel to create, convey, and communicate the image of a magnificent ruler over the Burgundian lands.

Jolivet has shown that the duke had a taste for combining black textiles made from different materials (wool, silk, linen) and of different weaves, including damasks and velvets, thus creating an ostentatiously rich, yet subtle tonality.[122] In the iconic full body portrait in the Chroniques de Hainaut, the ducal dress evokes the splendours of patterned velvets or costly damasks, and appears to be strikingly faithful to Philip the Good’s clothing preferences.[123] The illuminator’s mastery of a rich yet subtle black tonality reflects the historical evidence on ducal clothing and the consumption of black textiles at the Burgundian court.[124]

The masterly execution of sumptuous tonalites and textile textures in the presentation miniature of the Chroniques de Hainaut is programmatic, and is consequently also visible in the other presentation miniatures attributed to Dreux Jehan and Willem Vrelant [Figure 3 and 4]

and in other miniature portraits of Philip the Good, as in this Annunciation scene, showing the duke in a luxurious coat, subtly painted in different black and grey tones imitating costly patterns of a decoratively figured weave or applied tone-on-tone brocades. These details are barely visible to the naked eye, but can be revealed in raking light[125] and with other technical imaging techniques [Figure 1 and Figure 5j].

The illuminator’s attention to detail and liveliness is also apparent in the meticulous rendering of the pointed black shoes that appear to be painted in a slightly darker hue than the tight-fitting hoses. Underdrawings have shown that the painter changed his initial design in favour of a more idealized slender appearance of the ducal legs[126], but he did not straighten out the folds around the knees that come with actual wearing of woolen hose. We can discern small creases that were painted in by adding subtle highlights and shadows with whites and darker shades, calling to mind the rising demand for close-fitting knitted stockings in fifteenth-century Europe.[127]

Philip’s boldly cut pourpoint has the exquisite look of finely woven fabrics with which elaborate decorative patterns can be created tone-on-tone[128], thus creating a rich tonality of black shades. Here, too, we can discern a variation of a palmette/pomegranate design, visible in the throne cloth behind the duke[129] [Figure 1]. On the folio, the luxurious appearance of the ducal garment is imitated with a subtle play of accentuated, highlighted and shadowed areas, likely achieved with different black colourants and painting techniques, such as layers applied on top of each other and colour mixtures (see video Reworking a Variety of Black Pigments for Manuscript Illumination above). But which choices did illuminators have to create an everlasting image of their duke dressed up in black?

The incredible effort that generations of dyers undertook with labour-intensive and costly dye technologies to render fabric the luscious black so much coveted at European courts in the fifteenth and sixteenth century,[130] appears to stand in stark contrast with the abundant availability of black pigment for paint. Black soot, for example, was present in every kitchen, adhering to fireplace walls and cauldrons, or as charcoal remnants of extinct fires. The apparent mundanity of black colourants for painting raises the question of how Burgundian illuminators conveyed the lustrous richness of princely black shades on paper and parchment. Which materials and techniques did illuminators choose to convey their duke’s magnificence? I’ve showed in this essay that colour mattered to the duke and that black played an instrumental role in Burgundian politics and art; this paves the way for further research into the technical side of colour matters in Burgundian miniatures. This essay and Birgit Reissland’s contribution to Burgundian Black on “Black Colour Technologies for Burgundian Illuminators” can thus best be seen as a diptych: read together they offer a deeper understanding of Burgundian black splendours in miniature painting.

Bibliography

Anonymous. “MS.517 Wellcome Library ‘Collection of Alchemical, Technical, Medical, Magic and Divinatory Tracts (Miscellanea Alchemica XII),’” 15thc. https://archives.wellcome.ac.uk/DServe/dserve.exe?&dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqCmd=show.tcl&dsqDb=Catalog&dsqPos=0&dsqSearch=%28AltRefNo=%27MS.517%27%29.

———. “Dell’arte Della Seta. Plut.89 Sup. 117 Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana – Scaffale Digitale.” Florence, 1487.

Baldick, Chris. “Mise‐en‐abyme.” In The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Balfour-Paul, Jenny. Indigo in the Arab World. Richmond: Curzon, 1997.

Bartl, Anna, Christoph Krekel, Doris Oltrogge, and Manfred Lautenschlager. Der “Liber illuministarum” aus Kloster Tegernsee: Edition, Übersetzung und Kommentar der kunsttechnologischen Rezepte. Leiden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005.

Bennett, Adelaide Louise, and Patrick de Rynck, eds. Meesterlijke Middeleeuwen: Miniaturen van Karel de Grote Tot Karel de Stoute, 800-1475. Leuven: Davidsfonds & Brepols, 2002.

Blondeau, Chrystèle. “A Very Burgundian Hero: The Figure of Alexander the Great under the Rule of Philip the Good.” In Flemish Manuscript Painting in Context: Recent Research, edited by Elizabeth Morrison, Thomas Kren, et. al. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006.

———. “Jean Wauquelin et l’illustration de ses textes. Les exemples des Faicts et Conquestes d’Alexandre le Grand (Paris, BnF, ms. fr. 9342) et du Girart de Roussillon (Vienne, ÖNB, ms. 2549).” In Jean Wauquelin: de Mons à la cour de Bourgogne, edited by Marie-Claude de Crécy, Gabriella Parussa, and Sandrine HérichéTurnhout: Brepols, 2006. 213–24.

Bonito Fanelli, R. “The Pomegranate Motif In Italian Renaissance Silks: A Semiological Interpretation of Pattern and Color.” In La Seta in Europa. Sec. Xiii-Xx, Atti Della “Ventriquattresima Settimana Di Studi”, 4-9 Maggio 1992, edited by S. Cavaciocchi, 507–30. Florence: Le Monnier 1993.

Borchert, Till-Holger. “Imaging History – Imagining History.” In New Perspectives on Flemish Illumination, edited by Lieve Watteeuw, Jan van der Stock, Bernard Bousmanne, and Dominique Vanwijnsberghe. Leuven: Peeters, 2018. 3–23

Boulton, D’Arcy Jonathan Dacre, and Jan R Veenstra, eds. The Ideology of Burgundy: The Promotion of National Consciousness, 1364-1565. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2006.

Bousmanne, Bernard, and Thierry Delcourt, eds. Vlaamse miniaturen 1404 – 1482. Leuven: Davidsfond, 2011.

Braekman. “Antwerpse ‘Consten Ende Secreten’ Voor Verlichters En ‘Afsetters’ van Gedrukte Prenten,” Verslagen en mededelingen van de Koninklijke Academie voor Nederlandse taal- en letterkunde (new series) 1.1 (1994): 78-152.

Broecke, Lara. Cennino Cennini’s Il Libro Dell’arte: A New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription. London: Archetype Publishing, 2015.

Campbell, Lorne. “Rogier as a Designer of Works of Art in Media Other than Oil and Panel.” In Rogier van der Weyden in Context: Papers Presented at the Seventeenth Symposium for the Study of Underdrawing and Technology in Painting Held in Leuven, 22 – 24 October 2009 ; in Memory of Veronique Vandekerchove 1965 – 2012, edited by Lorne Campbell, Veronique Vandekerchove, and Jan van der Stock. Leuven: Peeters, 2012. 23–43

———. “Rogier van der Weyden.” In Vlaamse miniaturen 1404 – 1482, edited by Bernard Bousmanne and Thierry Delcourt, Leuven: Davidsfond, 2011. 174–77.

———. “Rogier van der Weyden and Manuscript Illumination.” In Flemish Manuscript Painting in Context: Recent Research, edited by Elizabeth Morrison and Thomas Kren. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006. 87-102.

———. “Suppliers’ of Artists’ Materials to the Burgundian Court.” In Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, edited by Jo Kirby, Susie Nash, and Joanna Louise Cannon. London: Archetype Publishing, 2010. 183–87

Campbell, Lorne, Veronique Vandekerchove, and Jan van der Stock, eds. Rogier van der Weyden in Context: Papers Presented at the Seventeenth Symposium for the Study of Underdrawing and Technology in Painting Held in Leuven, 22 – 24 October 2009 ; in Memory of Veronique Vandekerchove 1965 – 2012. Leuven: Peeters, 2012.

Cardon, Bert. “Boeken Aan Het Hof.” In Meesterlijke Middeleeuwen: Miniaturen van Karel de Grote Tot Karel de Stoute, 800-1475, edited by Adelaide Louise Bennett and Patrick de Rynck, 69–75. Zwolle : Leuven: Waanders ; Davidsfonds, 2002.

Cardon, Dominique. Le monde des teintures naturelles. Paris: Belin, 2014.

———. Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science. London: Archetype Publishing, 2007.

Cauchies, Jean-Marie. “Le Prince, Le Pays et La Chronique : Aux Surces d’un Intérêt Politique.” In Les Chroniques de Hainaut, Ou, Les Ambitions d’un Prince Bourguignon, edited by P. Cockshaw and Christiane van den Bergen-Pantens, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique., 15–16. [Brussels] : Turnhout, Belgium: KBR ; Brepols, 2000.

Chastellain, Georges (1405?-1475) Auteur du texte. Chronique des ducs de Bourgogne, par Georges Chastellain, 1827. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6227595m.

Childs, Wendy R. “Painters’ Materials and the Northern International Trade Routes of Late Medieval Europe.” In Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, edited by Jo Kirby, Susie Nash, and Joanna Louise Cannon, 29–41. London: Archetype, 2010.

Cholcman, Tamar. Art on Paper: Ephemeral Art in the Low Countries : The Triumphal Entry of the Archdukes Albert and Isabella into Antwerp, 1599. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2014.

Clark, Gregory. “De Meester van de Girard de Rouissillon (Dreux Jehan).” In Vlaamse miniaturen 1404 – 1482, edited by Bernard Bousmanne and Thierry Delcourt, 188–201. Leuven: Davidsfond, 2011.

———. “The Painters of Philip the Good’s Alexander.” In New Perspectives on Flemish Illumination, edited by Lieve Watteeuw, Jan van der Stock, Bernard Bousmanne, and Dominique Vanwijnsberghe. Leuven ; Peeters, 2018. 81–99.

Cockshaw, P., and Christiane van den Bergen-Pantens, eds. Les Chroniques de Hainaut, Ou, Les Ambitions d’un Prince Bourguignon. Bibliothèque royale de Belgique. [Brussels] : Turnhout, Belgium: KBR ; Brepols, 2000.

Crécy, Marie-Claude de, Gabriella Parussa, and Sandrine Hériché, eds. Jean Wauquelin: de Mons à la cour de Bourgogne. Turnhout: Brepols, 2006.

Davids, Karel. “Craft Secrecy in Europe in the Early Modern Period: A Comparative View.” Early Science and Medicine 10, no. 3 (January 1, 2005): 341–48. https://doi.org/10.1163/1573382054615398.

———. “Public Knowledge and Common Secrets. Secrecy and Its Limits in the Early-Modern Netherlands.” Early Science and Medicine 10, no. 3 (January 1, 2005): 411–27. https://doi.org/10.1163/1573382054615424.

De Guise, Jacques. “Chroniques de Hainaut, Vol. 1,” n.d. Ms. 9242. Bibliothèque royale de Belgique (KBR).

De Maesschalck, Edward. De Bourgondische vorsten 1315-1530. Leuven: Davidsfonds, 2019.

De Mayerne, Sir Theodore, et al., et al., and et al. “Pictoria, Sculptoria, Tinctoria at Quae Sub- Alternarum Artium Spectantia; in Lingua Latina, Gallioa, Italiea, Germanica Con- Scripta a Petro Paulo Rubens, Van Dyke, Somers, Greenberry, Janson &c. Pol. No XIX.” Manuscript. London, 1655 1620. British Library.

Degani, Laura, Chiara Riedo, and Oscar Chiantore. “Identification of Natural Indigo in Historical Textiles by GC–MS.” Analytical & Bioanalytical Chemistry 407, no. 6 (February 28, 2015): 1695–1704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-014-8423-2.

Deploige, Jeroen, and Peter Stabel. “Textile Entrepreneurs and Textile Workers in the Medieval City.” In Golden Times: Wealth and Status in the Middle Ages. Lannoo Publishers, 2016. 240–81

Docquier, Gilles. “Le Collier de l’ordre de La Toison d’or et Ses Representations Dans La Peinture Primitifs Flamands (XVe et Première Moité Du XVIe Siècle).” Annales de Bourgogne : Revue Historique Trimestrielle Publiée Sous Le Patronage de l’Université de Dijon et de l’Académie Des Sciences, Arts et Belles Lettres de Dijon 80, no. 1 (2008): 125–62.

Dubois, Anne. “La Scène de Présentation Des Chroniques de Hainaut. Idéologie et Politique à La Cour de Bourgogne.” In Les Chroniques de Hainaut, Ou, Les Ambitions d’un Prince Bourguignon, edited by P. Cockshaw and Christiane van den Bergen-Pantens. Turnhout, Belgium: KBR ; Brepols, 2000. 119–24.

———. “Techniques Picturales Des Grisailles Dans Les Manuscrits Enluminés Des Pays-Bas Méridionaux.” In New Perspectives on Flemish Illumination, edited by Lieve Watteeuw, Jan van der Stock, Bernard Bousmanne, and Dominique Vanwijnsberghe. Leuven ; Peeters, 2018. 233-48.

———. “Willem Vrelant.” In Vlaamse miniaturen 1404 – 1482, edited by Bernard Bousmanne and Thierry Delcourt, 238–55. Leuven: Davidsfond, 2011.

Edmonds, John. The History of Woad and the Medieval Woad Vat. Little Chalfont: J. Edmonds, 1998.

Frencken, Herman Gerard Theodoor. “T bouck van wondre, 1513.” Leiden University, 1934.

García-Frías Checa, Carmen. “Some Artistic and Technical Considerations on the ‘Portrait of Philip the Good’ in the Royal Palace of Madrid after Its Restoration.” In Rogier van der Weyden in Context: Papers Presented at the Seventeenth Symposium for the Study of Underdrawing and Technology in Painting Held in Leuven, 22 – 24 October 2009 ; in Memory of Veronique Vandekerchove 1965 – 2012, edited by Lorne Campbell, Veronique Vandekerchove, and Jan van der Stock. Leuven: Peeters, 2012. 169-78.

Gargiolli, Girolamo. L’arte Della Seta in Firenze;Trattato Del Secolo Xv,. Volume unico. Firenze, 1868.

Geelen, Ingrid., and Delphine. Steyaert. Imitation and Illusion: Applied Brocade in the Art of the Low Coutries in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Scientia Artis ; Dl. 6. Brussels: Koninklijk Instituut voor het Kunstpatrimonium, 2011.

Harris, Jennifer, and Patricia Baker. 5000 Years of Textiles. London: British Museum Press, 1993.

Hassan, Alttabi Furat Jamal, Xiang Yang Bian, and Xiao Yu Xin. “Artistic Influences Analysis of Iraqi National Costumes.” Advanced Materials Research 821–822 (September 2013): 735–45. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.821-822.735.

Hériché-Pradeau, Sandrine. “Girart de Roussillon : la stratégie hagiographique d’une compilation.” In Jean Wauquelin: de Mons à la cour de Bourgogne, edited by Marie-Claude de Crécy, Gabriella Parussa, and Sandrine Hériché. Turnhout: Brepols, 2006. 89-110.

Hofenk de Graaff, Judith H., Wilma G. Th Roelofs, and Maarten R. van Bommel. The Colourful Past: Origins, Chemistry and Identification of Natural Dyestuffs. London: Archetype Publishing, 2004.

Huizinga, Johan. Autumntide of the Middle Ages. Edited by Graeme Small and Anton van der Lem. Translated by Diane Webb. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2020.

———. Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen: studie over levens- en gedachtenvormen der veertiende en vijftiende eeuw in Frankrijk en de Nederlanden. Edited by Anton van der Lem, 2018.

Jolivet, Sophie. “La construction d’une image : Philippe le Bon et le noir (1419-1467).” Apparence(s), no. 6 (August 9, 2015).

———. “Le phénomène de mode à la cour de Bourgogne sous Philippe le Bon : l’exemple des robes de 1430 à 1442.” Revue du Nord n° 365, no. 2 (2006): 331–45.

———. ““Pour soi vêtir honnêtement à la cour de monseigneur le duc de Bourgogne: costume et dispositif vestimentaire à la cour de Philippe le Bon de 1430 à 1455″.” Université de Bourgogne, 2003.

Jolivet, Sophie, and Hanno Wijsman. “Dress and Illuminated Manuscripts at the Burgundian Court:Complementary Sources and Fashions (1430-1455).” In Staging the Court of Burgundy: Proceedings of the Conference “The Splendour of Burgundy” ; [… Took Place in the Concertgebouw in Bruges from 12 – 14 May 2009 …], edited by Wim Blockmans. London: Harvey Miller Publishing, 2013. 279-86.

Jugie, Sophie. “Les Portraits Des Ducs de Bourgogne.” Images et Représentations Princières et Nobiliaires Dans Les Pays-Bas Bourguignons et Quelques Régions Voisines (XIVe – XVIe s.), Publications du Centre Européen d’Etudes Bourguignonnes, 37 (January 1, 1997): 49–86. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.PCEEB.2.302224.

Kirby, Jo, Susie Nash, and Joanna Louise Cannon, eds. Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700. London: Archetype Publishing, 2010.

Kren, Thomas. “From Panel to Parchment and Back: Painters as Illuminators before 1470.” In Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe ; [Exhibition Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 17 June – 7 September 2003; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 29 November 2003 – 22 February 2004], edited by Thomas Kren, Scot McKendrick, and Maryan Wynn Ainsworth. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003. 81-121.

Kren, Thomas, and Maryan Wynn Ainsworth. “Illuminators and Painters: Artistic Exchanges and Interrelationships.” In Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe ; [Exhibition Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 17 June – 7 September 2003; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 29 November 2003 – 22 February 2004], edited by Thomas Kren, Scot McKendrick, and Maryan Wynn Ainsworth. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003. 35-58.

Kren, Thomas, Scot McKendrick, Maryan Wynn Ainsworth, et. al, eds. Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe ; [Exhibition Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 17 June – 7 September 2003; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 29 November 2003 – 22 February 2004]. Los Angeles, Calif: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003.

Kroustallis, Stefanos, and Rocío Bruquetas. “Paint It Red: Vermillion Manufacture in the Middle Ages.” In Making and Transforming Art: Technology and Interpretation. Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium of the ICOM-CC Working Group for Art Technological Source Research, Held at the Royal Institute of Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA), Brussels, 22 – 23 November 2012, edited by Hélène Dubois, Joyce H. Townsend, Jileen Nadolny, et. al. London: Archetype Publications, 2014. 23-30

Lambert, Bart, and Katherine Anne Wilson, eds. Europe’s Rich Fabric: The Consumption, Commercialisation, and Production of Luxury Textiles in Italy, the Low Countries and Neighbouring Territories (Fourteenth-Sixteenth Centuries). Burlington: Ashgate, 2015.

Leroi-Gourhan, André. L’homme et la matière. Paris: Albin Michel, 1943.

Long, Pamela O. Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Loo, Bart van. De Bourgondiërs: Aartsvaders van de Lage Landen. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij, 2019.

Monnas, Lisa. “Italian Silks (1300-1500).” In 5000 Years of Textiles, edited by Jennifer Harris, Repr., 1st edition 1992. London: British Museum Pr, 2012. 167-71.

Moodey, Elizabeth Johnson. Illuminated Crusader Histories for Philip the Good of Burgundy. Turnhout: Brepols, 2012.

Munro, John H. “The Anti-Red Shift to the ‘Dark Side’: Colour Changes in Flemish Luxury Woollens, 1300 – 1550.” In Medieval Clothing and Textiles, edited by Robin Netherton and Gale R Owen-Crocker, Vol. 3. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007.

Muthesius, Anna. “Silk in the Medieval World.” In The Cambridge History of Western Textiles, edited by D. T. Jenkins. Cambridge, U.K. ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003. 325-54.

Nash, Susie. “‘Pour Couleurs et Autres Choses Prise de Lui…’: The Supply, Acquisition, Cost and Employment of Painters’ Materials at the Burgundian Court, c. 1375-1419.” In Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, edited by Jo Kirby, Susie Nash, and Joanna Louise Cannon. London: Archetype Publishing, 2010. 97-181.

Panayotova, Stella, Deirdre Elizabeth Jackson, and Paola Ricciardi, eds. Colour: The Art & Science of Illuminated Manuscripts. London Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2016.

Panayotova, Stella, and Paola Ricciardi, “Manuscripts in the Making: Art & Science,” Heritage Science 7, no. 60 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0302-x.

Parussa, Gabriella, and Richard Trachsler. “La Scripta de Jacotin Du Bois, Un Copiste Dans l’atelier de Jehan Wauquelin.” In The Ideology of Burgundy: The Promotion of National Consciousness, 1364-1565, edited by D’Arcy Jonathan Dacre Boulton and Jan R Veenstra. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2006. 185-200.

Pastoureau, Michel. Black: The History of a Color. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2009.

———. “Wapens, spreuken, emblemen. Heraldische gewoonten en motieven in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden en aan het Bourgondische hof in de 15e eeuw.” In Vlaamse miniaturen 1404 – 1482, edited by Bernard Bousmanne and Thierry Delcourt. Leuven: Davidsfond, 2011. 89-102.

Phipps, Elena. Looking at Textiles: A Guide to Technical Terms. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.

Piérard, Christiane. “Conclusions Ou La Siignification de l’édition Des Chroniques de Hainaut Au Milieu Du XVe Siècle.” In Les Chroniques de Hainaut, Ou, Les Ambitions d’un Prince Bourguignon, edited by P. Cockshaw and Christiane van den Bergen-Pantens, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique. [Brussels] : Turnhout, Belgium: KBR ; Brepols, 2000. 169-75.

Pleij, Herman. “Boeken Dragen.” In Meesterlijke Middeleeuwen: Miniaturen van Karel de Grote Tot Karel de Stoute, 800-1475, edited by Adelaide Louise Bennett and Patrick de Rynck. Zwolle : Leuven: Waanders ; Davidsfonds, 2002. 35-45.

Ploss, Emil. Ein Buch von alten Farben: Technologie der Textilfarben im Mittelalter mit einem Ausblick auf die festen Farben. Munich: Moos, 1977.

Ravaud, Elisabeth. “The Contribution of X-Radiography to the Study of Applied Brocade.” In Imitation and Illusion: Applied Brocade in the Art of the Low Coutries in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, edited by Ingrid. Geelen and Delphine Steyaert. Brussels: Koninklijk Instituut voor het Kunstpatrimonium, 2011. 179-86.

Reissland, Birgit. “Why Do Artists Prefer Vine or Willow Charcoal?” Journal of Paper Conservation 15, no. 4 (2014): 6.

Reynolds, Catherine. “Illuminators and the Painters’ Guilds.” In Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe ; [Exhibition Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 17 June – 7 September 2003; Royal Academy of Arts, London, 29 November 2003 – 22 February 2004], edited by Thomas Kren, Scot McKendrick, and Maryan Wynn Ainsworth. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003. 15-34.

Richard, Jean. “Le Contexte: L’Etat Bourguignon.” In Les Chroniques de Hainaut, Ou, Les Ambitions d’un Prince Bourguignon, edited by P. Cockshaw and Christiane van den Bergen-Pantens, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique. [Brussels] : Turnhout, Belgium: KBR ; Brepols, 2000. 9-11.

Roussel, Claude. “Les Rubriques de La Belle Hélène de Constantinople.” In The Ideology of Burgundy: The Promotion of National Consciousness, 1364-1565, edited by D’Arcy Jonathan Dacre Boulton and Jan R Veenstra. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2006. 201-12.

Rublack, Ulinka. “Renaissance Dress, Cultures of Making, and the Period Eye.” West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 23, no. 1 (March 1, 2016): 6–34. https://doi.org/10.1086/688198.

Scarce, Jennifer M. “Book Review: Indigo in the Arab World by Jenny Balfour-Paul.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 26, no. 2 (November 1999): 336.

Schandel, Pascal. “De Meester van de Alexandre van Waquelin.” In Vlaamse miniaturen 1404 – 1482, edited by Bernard Bousmanne and Thierry Delcourt. Leuven: Davidsfond, 2011. 178-82.

———. “Opdrachtscènes aan het hof van de Bourgondische hertogen. Bronnen en intenties van een genre.” In Vlaamse miniaturen 1404 – 1482, edited by Bernard Bousmanne and Thierry Delcourt. Leuven: Davidsfond, 2011. 66-80.

Schnerb, Bertrand. “De Bourgondische hertogen en hun ‘landen herwaarts over’ in de 15de eeuw.” In Vlaamse miniaturen 1404 – 1482, edited by Bernard Bousmanne and Thierry Delcourt. Leuven: Davidsfond, 2011. 38-46.

Scott, Margaret. “The Role of Dress in the Image of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy.” In Flemish Manuscript Painting in Context: Recent Research, edited by Elizabeth Morrison and Thomas Kren. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006. 43-56.

Serrano, Ana. “The Red Road of the Iberian Expansion – Cochineal and the Global Dye Trade.” Centro de História d’Aquém e d’Além-Mar, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa e Universidade dos Açores, 2016.

Small, Graeme. “Les Chroniques de Hainaut et Les Projets d’historiographie Régionale En Langue Française à La Cour de Bourgogne.” In Les Chroniques de Hainaut, Ou, Les Ambitions d’un Prince Bourguignon, edited by P. Cockshaw and Christiane van den Bergen-Pantens. Brussels: Turnhout, Belgium: KBR ; Brepols, 2000. 17-22.

———. “Of Burgundian Dukes, Counts, Saints, and Kings (14 C.E. – c. 1500).” In The Ideology of Burgundy: The Promotion of National Consciousness, 1364-1565, edited by D’Arcy Jonathan Dacre Boulton and Jan R Veenstra. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2006. 151-94.

Smeyers, Maurits. Flemish Miniatures: From the 8th to the Mid-16th Century ; the Medieval World on Parchment. Leuven: Davidsfonds, 1999.

Smith, Pamela H., Tianna Helena Uchacz, Sophie Pitman, et. al. “The Matter of Ephemeral Art: Craft, Spectacle, and Power in Early Modern Europe.” Renaissance Quarterly 73, no. 1 (2020): 78–131. https://doi.org/10.1017/rqx.2019.496.

Spring, Marika. “The Materials of Rogier van der Weyden and His Contemporaries in Context.” In Rogier van der Weyden in Context: Papers Presented at the Seventeenth Symposium for the Study of Underdrawing and Technology in Painting Held in Leuven, 22 – 24 October 2009 ; in Memory of Veronique Vandekerchove 1965 – 2012, edited by Lorne Campbell, Veronique Vandekerchove, and Jan van der Stock. Leuven: Peeters, 2012. 93-107.