In collaboration with the renowned textile artist Claudy Jongstra, we explored and revived Burgundian black colour technologies for the exhibition ‘Back to Black’ (Summer 2019 – Summer 2021) at the Museum Hof van Busleyden, a museum for Burgundian culture, in Mechelen. As discussed elsewhere in this book, the historical background to this exhibition was the Burgundian court and its role in making black clothes fashionable, and Flemish master dyers perfecting the art of dyeing deeply dark and intense tones of black in the Burgundian-Habsburg Netherlands.[1] Jongstra reinvested the revived black dyes in her art work and haute couture fashion, and Burgundian black fashion design, incorporated by Viktor & Rolf, has made it recently to the catwalks of Paris, New York and Milan. From the point of view of the contemporary artist, Burgundian black can best be thought of as a ‘Re-invention’, a kind of ‘Re’practice which is quite common throughout the history of technology.[2]

The Burgundian Black Collaboratory, an expert workshop at Claudy Jongstra’s farm in Friesland from 16 – 18 January 2019. Film by Joshua Pinheiro Ferreira, PADRE FILMS (https://padrefilms.com/) for the Back to Black exhibition at Museum Hof van Busleyden.

Jongstra’s installation ‘Expanding Field’, produced for ‘Back to Black’ was a co-creation with members of the public who were learning about black dyeing. Throughout the two-year period that the exhibition was on view, the work changed and grew with the participation of the public that had the opportunity to attend historically-inspired black dyeing workshops and to add self-dyed woolen strings from the artists’ studio to the installation.[3] The interactive installation was displayed in the participatory space of the museum where visitors could walk through the strings, and touch and smell the expanding field of black dyed wools (video impression Expanding Field by Artechne/Boulboullé). The space also featured two tables with samples of wools and silks that had resulted from reworkings of historical black dye recipes, also on view in the exhibition space (for impressions of the exhibition see the scrapbooks spread throughout this essays as well as the essay by Samuel Mareel and Marijke Wienen in this collection). Under the motto ‘A colour you can feel’ visitors were invited to take part in participatory research about the sensory perception of the colour black, and the different shades, tones and textures of the black samples, developed together with Asifa Majid, a colour language specialist.[4] Jongstra discusses her artistic practice elsewhere in this book, and Mareel and Wienen situate the meaning of the participatory space in the museum.[5]

Reworking the recipe ‘Noir de Flandres’ (1646) with Jenny Boulboullé and Art Proaño Gaibor, Atelier Building Amsterdam. A film by Katrien Vanagt and Stefano Bertacchini, 2020 @Serafín Productions for ARTECHNE.

The historical research we undertook for this project included a 3-day expert workshop in Húns, The Burgundian Black Collaboratory (14-16 January 2019), hosted by Jongstra and members of her studio and of Extended Ground [6] she set up with her partner Claudia Busson in Friesland, and co-organized by Jenny Boulboullé together with Natalia Ortega Saez (University of Antwerp) and Art Gaibor Proaño (Cultural Heritage Agency Research Laboratory).[7] The contributions of our partners, several participants of The Burgundian Black Collaboratory, and other experts can be found elsewhere in this volume.

The historical knowledge of Burgundian black colour technologies was thus created in a participatory and collaborative space, and it is the importance of this site for ‘Re-’ practices in historical research which is the focus of this chapter. The participatory spaces included teaching and research laboratories in Amsterdam and Antwerp, and the artists’ studio and farm in rural Friesland, allowing us to profit from the local ecology of dyestuffs grown in Jongstra’s garden and the dyeing expertise of Jongstra and her team. Reworking recipes, as a method of historical inquiry, at different sites, in and especially outside the laboratory, has particular strengths which are key to understanding Burgundian black, and early modern colour worlds more generally. While it is well-known that ‘Re-’ research brings out the importance of the historicity of the materials, in this chapter we will emphasize the significance of the environments, spaces, and ecologies in which we perform this research if we want to gain access to the gestural and sensory knowledge invested in historical processes of colour production.[8] Starting with some methodological reflections on our recipe reworkings as a form of ‘Re’-research, we then present in this essay an extended narrative that weaves together our research experiences in the laboratory and at the artists’ farm with historical knowledge. We support this extended narrative with several ‘scrapbook’ entries that give the reader a more visual and associative impression of our approach, combining field notes, snapshots and archival findings from our colour research into Burgundian Black that Boulboullé collected in the course of this collaborative book and exhibition project.

As we have argued in the book Early Modern Color Worlds, the idea of Newtonian colour science as a point of culmination of the development of colour knowledge has made room for the recognition of a plurality of pre-Newtonian colour worlds, each consisting of objects, concepts, and practices based on distinct materials and productions.[9] It seems that until the nineteenth century and (in the words of Regina Blaszczyk) the ‘colour revolution’ following the industrial production of synthetic dyes and pigments, there was no systematization and standardization across these different early modern colour worlds.[10] This is not to say that these were worlds apart. The period around 1600 witnessed the intensification of attempts at communication between these colour worlds. In fact, Newton’s debt to artists, who redefined the role of black and white in the colour order, for the development of his colour theory is a fine example of such cross-world communication.[11] Prior to the establishment of the Newtonian scheme, other colour systems were more locally determined. In the eighteenth century, for instance, Tobias Mayer, a professor of mathematics at the university of Göttingen, and Johann Heinrich Lambert, a member of the Preussische Akademie in Berlin, invented colour systems.[12] Not only were these colour systems practice-based (that is, they were strongly informed by colour knowledge developed in the arts) they were also imagined to be for practical use. We can also observe the practice-based colour worlds in early modern colour economies. Large textile swatch books — immortalized in Rembrandt’s and Jan de Baen’s famous seventeenth-century portrait paintings of sampling officials — became the main tools for strict colour quality controls in the guild-regulated textile centres of the Low Countries, like the one devoted to black colours and shades at the city’s former cloth hall, Museum de Lakenhal in Leiden.[13] Prior to the invention of colour systems and the standardization following the colour revolution, variability remained a key characteristic of early modern colour worlds.

Behind the Scenes with Claudy Jongstra’, A film by Marit Geluk for Museum De Lakenhal, 2020 ©Marit Geluk for Museum De Lakenhal

Reworking recipes allows us to see variability as a key characteristic of early modern colour worlds, and we found it necessary to move our reworking practices between sites in and outside the laboratory in order to experiment with various conditions. Originally, like many others engaged in historical ‘Re-‘ research, we took up our work at the Atelier Building, where the University of Amsterdam, the Rijksmuseum, and the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands gathers its expertise in the conservation and preservation of art objects.[14] The Atelier Building hosts modern state-of-the-art conservation studios and laboratories, which are very different from the historical workshop environments in which we, as both the objects and subjects of study, are interested. For example, temperature control was very different in early modern furnaces than in a modern lab, and such differences are important in estimating the authenticity of the reconstruction and the historical accuracy of the reproduction. However, one can wonder if the laboratory environment is not more fundamentally important to the production of historical knowledge through ‘Re-’ practices. Historians of science have made great efforts in the past half a century to emphasize that site matters and that scientific knowledge is shaped and legitimized by its place of production.[15] We suggest self-reflectively turning this insight on to our own practices of reconstruction in the laboratory, and we consider how the laboratory matters to us as a place of knowledge production. Does it matter, we ask, if we produce historical knowledge in the laboratory or a field?

In this chapter we will reflect on the epistemological significance of the sites in which ‘Re-’ research takes place. The reconceptualization of the collaborative and participatory spaces of our reworking of recipes was not invented from scratch, but was rather the outcome of interdisciplinary cross-fertilization in ‘Re-’ research.

Histories of ‘Re-‘ Research

Performative methods play an increasingly prominent role in research into historical production processes, materials, and bodily knowledge and sensory skills, and in forms of education and public engagement in classrooms and museums. Such methods are used across fields in the humanities and social sciences, from history of science and technology to archaeology, art history, and conservation, to musicology and anthropology, among many other disciplines. A variety of ‘Re-’ terms are used in relation to these performative methods — Reconstruction, Reenactment, Replication, Reproduction, Reworking — and different disciplines have acquired preferences for particular ‘Re-’ terms. Reconstruction is the term of choice in conservation and restoration and in reference to digital or virtual reconstructions in archaeology; the ‘replication method’ is the point of reference in the history of science; and reenactment seems to be the more common term in musicology and anthropology. One could argue that the typical ‘Re-’ terms which disciplines have adopted reflect their acquired preferences for either process or product-oriented ‘Re-’ research practices.[16]

Nevertheless, the use of specific ‘Re-’ terms within a discipline is also the outcome of the rich historiographical traditions of ‘Re-’ research within these disciplines. In several disciplines, performative methods of redoing history go back decades, sometimes even more than a century. For example, experimental archeology has roots in the nineteenth century, and the same is true for reconstruction in conservation and restoration, which emerged in conjunction with the interest in the recovery of the lost techniques of the old masters in the mid-nineteenth century. Here we will refer to those disciplines which have been most important to the design of ‘Re-’ methods in the research on Burgundian black: history of science and technology, archaeology, and anthropology and ethnography.

Opening the black box of skill (or tacit or gestural knowledge) has been a central concern of experimental history of science, as conceived by Otto Sibum in the 1990s.[17] Inspired by Falk Riess’ addition of a laboratory course using replicas of historical scientific instruments to the physics teacher training programme at the University of Oldenburg, historian of science Sibum started reworking historical experiments using carefully-reconstructed instruments. Experimental history of science uses a wide variety of ‘Re-’ terms. The only term which is considered misleading is ‘replication’, because of its associations with its present-day scientific usage of repetition of an experiment to check or confirm the validity of prior results. The aims of historians of science are quite different: ‘When historians rework or reproduce a process or an experiment as a historiographical tool they are not replicating in these scientific […] senses, but are instead seeking fresh historical information’.[18] In recent years, history of science appears to have converged towards ‘reworking’ as the term of preference, because the term puts the emphasis on process rather than product. For these reasons, we have also adopted the term ‘reworking’ instead of ‘reconstruction’, which is the more common term adopted in studies of art history, conservation, and restoration.

Findings from archaeology also inform the design of our ‘Re-’ method. While experimental archaeology has roots in the nineteenth century when archaeologists attempted to recreate the technologies of the past, it was only in 1979 that John Coles published a book on experimental archaeology, thus establishing the discipline of the same name.[19] In a special issue of World Archaeology on experimental archaeology, Alan Outram, professor of archaeological science, stated that one typical characteristic of experimental archaeology is that it is done in the field. He differentiated between experimental archaeology and experiments or tests in the laboratory, while specifying how they relate: ‘A gulf is left between such laboratory work and how such processes may have been achieved in the past, with a limited range of materials, technologies and a lesser control upon the environment. Experimental archaeology comes into its own at this point. What has been learned in the lab can now be taken further; hypotheses can be tested in a range of environmental conditions that aim to reflect … “actualistic” scenarios’.[20] To emphasise this open-air (as in, outside the controlled environment of the lab) character of experimental archaeology, Outram spoke of ‘actualistic’ experiments. The use of the term ‘actualistic’ also recognizes the much-discussed issue with the ‘re’ prefix which misleadingly suggests that archaeologists aim to reconstruct the past as it was in such experiments. In this chapter we also use the term ‘actualisation’ as it resonates with the activism of Jongstra’s artistic practice, based on reinvention, in which historic recipes embodying the past and partly forgotten colour knowledge are actualised for the creation of future colour worlds.

The defining move of experimental archaeology from the laboratory to the field came with particular epistemic challenges. Until recently, such practices of reenactment were primarily associated with living history, which uses performances to recreate past lifeways, showcasing a particular preference for the restaging of significant historical events, such as World War II battles. While such events at cultural heritage sites were important vehicles for the transmission of historical knowledge to the public, living history was regarded with disdain in academic circles, famously captured in the Australian ethno-historian Greg Dening’s view of reenactment as ‘the past dressed up in funny clothes’.[21] Indeed, to safeguard its methodology as scientific, experimental archaeologists have long distanced themselves from such recreational and educational evocations of past life and technology by reenactment groups dressed up in period costume. However, in more recent years, some experimental archaeological projects have embraced closer connections to these practices. One example is the Iron Age Village in Sagnlandet Lejre, a Historical-Archaeological Experimental Centre in Denmark, which was studied in the 1990s by an anthropologist who participated in the life of the Iron Age Village.[22] Another example of ‘experimental archaeology in action’, closer to our topic, is the building of a Burgundian castle with medieval techniques and materials in France. Situated in the northern part of Burgundy — where master builders work in collaboration with different public groups, including students, scientists, and interested amateurs — this building site is of scientific, historical, and educational interest. The project, known as Guédelon, is not a reconstruction of an actual historical site, but a ‘new-build’ that started in the 1990s; it involves a long-term commitment that allows archeologists to study construction processes that make it ‘necessary to sometimes “unlearn”, take down, start again, doubt, before finally feeling the right track’.[23] In such projects, ‘citizens’ are involved in experimental archaeological research on equal terms with professional archaeologists.

Anthropologists have also taken such practices of reenactment as a focus of their work. Petra Tjitske Kalshoven, for example, writes about Indian hobbyism, or Indianism in Europe, a racist practice that developed out of a strong fascination with Native American life in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[24] Given its partial origins in such living history and reenactment communities, we are currently witnessing a shift from an amateur pastime to a more stable, historical knowledge-producing, field of study. There are clear signs of this process of institutionalization, including the appearance of handbooks, such as The Routledge Handbook for Reenactment Studies (2020), and the construction of a shared cross-disciplinary history of the field of ‘Re-’ research, as we have undertaken in our volume Reconstruction Replication Re-enactment in the Humanities and Social Sciences (2020).[25]

Skill, Bodies, and Designs of ‘Re-‘ Research

The Routledge Handbook for Reenactment Studies observes a shift in the field towards ‘performance studies, with its emphasis on the body as an evidentiary vehicle for historical knowledge making’.[26] While ‘Re-’ practices are developed upon the premise that our bodies are research tools, they are not infallible witnesses. Bodies and our ways of doing — whether walking, eating, dancing or painting — are developed in a particular place and time, and thus, our performances engaging with material culture and the embodiment of past practices of bodies will always be partial, and always fail, yet in historically informative ways.

Given the role the body plays in the production of knowledge, models of knowledge production in ‘Re-’ practices are based on enactive approaches to perception and cognition. In enactive approaches, movements of the body are central to cognition, and perception is based on implicit knowledge of how bodily movement gives rise to changes in sensory stimulation. How bodies are capable of grasping the world ‘depends upon the possibilities given in the structure of their embodiment, how they have learned from experience, and the affordances of what they encounter’.[27] Scholars in performance studies, such as Maaike Bleeker, have pointed out the importance of reenactments created by dance makers, to reflect on the ways in which ‘Re-’ practices produce historical knowledge. She refers to Katie King’s work on reenactments on television in which she proposes re-enactment as a perspective on newly emerging modes of embodied cognition.[28] Based on examples, such as the television program ‘Leonardo’s dream machines’, which combine reconstructions of machines, reenactment of historical scenes by actors, interviews, historical documentation and museum objects, and computer simulations, King argues that reenactments are ‘pastpresents’, producing in their audiences cognitive sensations as they navigate across knowledge worlds. Reenactments thus involve a shift towards the experience of knowledge in the making, which results from ways of navigating across these knowledge worlds.

We have taken this account of reenactment as a point of departure in designing ‘Re-’practices in which we explore questions of skill and technique, and processes of learning, in the arts.[29] We are not just interested in skill — what it is and how it is acquired — but also in the role which texts of different genres, such as recipes, instructions, and manuals, play in the historical processes of learning of arts and crafts. If we know that texts have played only a limited role in learning a trade within the context of master-apprentice relationships in the workshop and that learning by doing remained the standard, how could early modern people have used texts, complementary to learning by doing? We thus rework recipes and instructions not only to reflect on the relation between texts and practice, but to gain insight into what artisans did with texts in the past, and how historic recipe texts can be acutalized today in collaborative re-research (practices of reinvention) with artists.

In response, we have designed our ‘Re-’ practice, especially the social environment in which we have placed the historian’s body, adopting elements of the ethnographic experiment. Upon the suggestion of the anthropologist Anna Harris during a NIAS-Lorentz Workshop on performative methods in Leiden, we re-performed an ethnographic experiment which a group of anthropologists, headed by Annemarie Mol, had previously performed.[30] The aim of the experiment was to shed light on an issue on which the anthropology of the senses was silent, that is, the issue of ‘finger tasting’, or the way that taste is mediated by the fingers rather than being confined to the tongue. The ethnographic experiment brought together a group of people who bought the ingredients and gathered in a kitchen of an apartment in Amsterdam to collectively prepare, cook, and eat a meal with their fingers. The experiment, as the anthropologists explicitly stated, was not set up to study the body and the sense of taste; it did not deliver ‘general knowledge about tasting fingers’, but ‘a particular configuration of what tasting fingers may be’ in which the challenge was to articulate this sensation.[31] Participants in the experiment mixed the roles of researcher-subject and object of research, mixed being the lab technician and the guinea pig. They called the singular event in which they engaged an experiment, but unlike laboratory experiments, there was no protocol.

The group of participants in the experiment had different cultural backgrounds, and while some were novices, others were experts in eating with their fingers. We undertook this experiment, hoping to learn what it meant to eat with one’s fingers, which requires distinct techniques depending on the different consistencies, temperatures, and textures of foods. ‘The experiment staged reality. It staged a strange bodily practice (for the novices), or staged a familiar practice in a strange way (for the experts)’.[32] And as the participants at the dinner observed, it was not the same event for each of them: ‘For the experts, there was a challenge in articulating the familiar; for the novices, finger-eating was a transgression – pleasant, awkward, or both’.[33] In the staged reality of the ethnographic experiment, experts (or eaters) meet novices (here the professional anthropologists) on an equal level; both groups bring different techniques and bits of knowledge, and learn from each other. It is this model of cooperation with makers which we have explored in our design of a ‘Re-’ method. While, in the interpretation of historical texts on practices of making, historians are typically the experts, we have created a setting in which historians, cultural heritage scientists, and expert makers meet on equal terms. The Burgundian Black Collaboratory provided a space where knowledge was embodied and distributed over multiple bodies of makers, heritage scientists, and historians.

One of our reenactments was focused on learning the craft of silversmiths, in which Thijs Hagendijk, Ph.D student and novice, apprenticed with metal conservator and gold and silversmith Tonny Beentjes.[34] Reenacting the socio-material environment of learning a craft, we placed a novice apprentice in a conservation studio with tools and equipment together with a master craftsman and a historical manual. Reflecting on Thijs’ learning process and Tonny the master’s pedagogy, reenactments provided insights into the role of texts in the process of learning in the arts, now and back in the early modern period. Our primary textual source was the early eighteenth-century guidebook by the Dutch silversmith Willem Van Laer.[35] Reworking Van Laer’s instructions, guided by the master, Thijs acquired access to sensory and gestural knowledge, which is absent or sometimes just invisible at first reading in the historical text, and also gained insight into why Van Laer wrote down his craft experience in the ways he did.[36]

The environment in this reenactment was a state-of-the-art, stainless steel conservation studio in the Atelier Building in Amsterdam which in its material attributes — the materials and tools, the fire and air-circulation technologies, and layout of the space — is significantly different from the eighteenth-century gold and silversmithing workshop in which Van Laer worked. In consequent reenactments we have moved — following in the footsteps of experimental archaeologists — ‘into the field’, or into open-air spaces with a different range of materials, other technologies, and less control upon the environment, which indeed might be closer to the material conditions under which processes of making were achieved in the past, as experimental archaeologists claim. More significantly, this move outdoors made sense because, as we have just seen, how people as embodied minds make sense of the world depends upon the affordances of the things they encounter in their material environments. According to the ecological psychologist James Gibson, an affordance means a possibility for action (whether walking, eating, painting) that the socio-material environment offers to us (those embodied minds in a landscape of affordances). Practices through which people acquire skills generate a selective openness to those affordances which allow apprentices to follow more experienced practitioners.[37]

If we think of skills and their acquisition in this way, it is important to rethink and accordingly materially shape the spaces in which we undertake our re-enactments. It is equally important to keep in mind that these socio-material environments ‘in the field’ are still and by necessity different from early modern workshops. The cognitive philosopher and artist-architect Erik Rietveld has explored ideas of skills in ‘The End of Sitting’, a site-specific installation allowing bodies to interact with material structures while exploring what kind of affordances for support standing people enjoyed.[38] Rietveld conceives of such installations as ‘material playgrounds’, and thinking of these socio-material environments in terms of playgrounds is also useful for reconstruction research because the element of play emphasizes the difference and interconnectedness of the past and the present (as in pastpresents), while play is also considered serious, and a key element in pedagogies.

We have arrived at a crucial moment in the history of ‘Re-’ research. Creating a common genealogy across the various disciplines, as we are currently witnessing, is an important step towards the formation of a field of study, which will also make it possible to enrich the design of ‘Re-’ methods by interdisciplinary cross-fertilization. However, to make this field sustainable and to ensure it produces meaningful historical knowledge, we will also need to develop an epistemology of ‘Re-’ practices. The ways in which we conceptualize and socio-materially scaffold the spaces in which we perform ‘Re-’ practices are key to such a theory of how ‘Re-’ practices produce and actualize historical knowledge. We propose to think of these spaces as material playgrounds in which experts of various kinds — makers, artists, historians, and conservators — responding to the affordances of these spaces, co-create historical knowledge.

Reworking Recipes, Reconstructing Burgundian Black Colour Worlds

How did we apply these insights into the importance of spaces in- and outside the laboratory to the design of our ‘Re-’ research on early modern colour worlds? What was the importance of the socio-material environments to our reconstructions of these colour worlds?

We use a scrapbook for presenting observations and findings of our collaborative research at different reworking sites.[39] Scrapbooking is a method of preserving, presenting, and arranging diverse memorabilia or forms of documentation, such as pictures, cuttings, or drawings. Scrapbooks also frequently contain extensive journal entries or written descriptions.[40] Scrapbooking is a way of ‘cutting out’ bits and pieces of information and bringing them into a different context or environment, which also describes nicely our approach to historical recipe reworkings: we simply brought the recipe texts we found in (digital) archives and libraries as ‘cut outs’ into laboratories and workshops.

From the Library to the Artist’s Studio: Sourcing Recipes and Waste[41]

The potential of the countryside is extraordinary. You can do so many beautiful things there that would perhaps be more difficult to do in an urban environmant. We can radically experiment here. To give an example. We started a bakery here three months ago. You can just do that here. You have a shed in the countryside and then you can bake bread. . . . and really good bread of great quality. [You can find] farmers here that grow grain for your biodynamic village. . . . It’s cool, find millers, it’s still very close to the life cycle — if you have a sense for that or you find that important — then you can find this here and expressing your appreciation for this makes people feel proud to be part of a community. . . . [T]he people here are makers, under the radar these are people that embody such wonderful qualities.

— Claudy Jonstra, in conversation, 2018

In search for more space, Jongstra migrated from the city to the Frisian countryside. Her studio in the small Frisian village Spannum kept expanding, but when this location became too small to do farming, they expanded their activities to a farm in Húns, a few kilometres further east.

‘We always do it this way. We start with an idea and then people sometimes ask me: do you have a business plan? We just start and then when you let things unfold organically, you come across fantastic turnarounds that you could not have seen if you had followed a straight path. This way beautiful things happen’.[42]

In the autum of 2018, one of us (Jenny Boulboullé) visited Jongstra at her studio in the small village of Spannum in Friesland. I stayed there with my daughter for a few days so that I could get an impression of the artists’ working space and to discuss our plans for investigating collaboratively how dyers produced Burgundian black in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. During our stay Jongstra invited us to engage in some daily activities. On the first day I helped her team members with dyeing wools yellow with freshly harvested Marigold flowers (Calendula officinalis L.) that had been picked the day before. On the next day I cycled with my daughter to Húns, a small Frisian village a few kilometres away, where Jongstra and Busson have a farm called De Kreake, home to the initiative Farm of the World — now Extended Ground — they started in 2018.[43] Every Wednesday, fresh sourdough bread is baked there in a stone oven. We also saw a field with colourplants, several Drenthe Heath sheep they keep on their farm, and we visited the greenhouse where they had just started to cultivate a Japanese indigo plant.[44] During this visit I was mostly interested in the colour and textile technologies that Jongstra specialized in: felting with wools dyed with organic colours. The rural environment opened up avenues for research into colourmaking practices with natural colourants.

Today, heritage scientists, technical art historians, restorers, and artists frequently order ‘historic’ pigments and natural dyestuff for reconstruction experiments from companies like the German Kremer Pigmente, providing products for the preservation, conservation, and art worlds, and the colour mill Verfmolen de Kat, a Dutch mill dating from 1781, that specializes in the production and trade of ‘historic’ artists’ materials.[45] Jongstra’s special interest in the sustainable cultivation of her own materials in collaboration with farmers, producing ‘homegrown’ wools and natural colourants, provided for us a new research context. Conducting our recipe reworking with Jongstra on site in a rural environment instead of in an urban laboratory setting with products purchased from artists’ material suppliers offered us a glimpse of the interwoven material colour ecologies that easily remain out of sight when working with the products of specialized art material suppliers.

When we arrived in the warm farm kitchen, the bread dough had already been kneaded and had risen. My daughter helped to make two cuts into each round loaf with a big knife, then she helped to open the burning-hot metal doors, while the baker placed the bread loaves with a swift movement into the heart of the oven. When they closed the doors, it caught my attention that the black smoke from the oven had covered the walls around the doors with a thick layer of black remnants.

The sight of the blackened walls brought to mind a sixteenth-century recipe in an anonymous French manuscript (BnF Ms Fr 640, fol. 93v) mentioning a black pigment bistre in a recipe for face paint. We were familiar with this recipe from rewokings with a graduate student in the Making and Knowing reconstruction laboratory at Columbia University in 2016, where one of us (Boulboullé) had co-taught lab seminars between 2014 and 2016.[46]

[…] The best bistre is the greasy & shiny kind from the fireplaces of large kitchens. It is difficult to grind & screeches on the marble.[47]

The recipe discusses how to work bistre (or bister) into a paint and advises that this black pigment can best be tempered with a water-based binder, like egg glair or animal glues, ‘for in oil it has no body & would not dry but with great difficulty’.[48] These detailed observations on paint properties suggest that the writer shares here experience-based colour knowledge. He also specifies in the recipe where this pigment can best be sourced: ‘from the fireplaces of large kitchens’. These kinds of black soot pigment were abundant in the past and much used by painters and illuminators. (On black pigment recipes for illuminators see “Black Color Technologies for Burgundian Dyers, c. 1350-1700“, as well as the “Practical Guide for the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700“, both by Birgit Reissland elsewhere in this volume).

In search of colour knowledge related to the sumptuous black dresses that became so fashionable under Burgundian reign, we later found in the same manuscript a recipe for ‘Velvets and blacks’ (Velours et noirs, BnF Ms Fr. 640, fol. 63v) with detailed instructions for rendering the subtle tonalities of black velvets in paint:

[…] For blue & green velvets, you highlight touch the shading with peach pit black, which is very black. For lake, black of pit coal which makes a reddish black lake for velvets. The common charcoal makes a whitish black.[49]

This recipe testifies to a rich palette of black shades that can be sourced from domestic (kitchen) waste, like common charcoal and burnt fruit pits. And burnt peach stone, a black pigment favored by illuminators and oil painters, does not only appear in painting recipes. The search for sixteenth-century black dye recipes turned up a rare recipe for black dyeing with linseed oil and the blackened pits of peaches. It is listed under the title ‘negro bellissimo‘ (p. 13) in an Italian ‘dyers’ manual’, the Plictho de l’arte de tentori (1548), one of the first printed recipe books on dyeing, that saw many editions and translations.[50] Also, the fine soot from burning incense (a resinous substance) was not only used as a pigment for watercoloring by illuminators, but also appears in a medieval black dye recipe (Cgm 720, fol. 229v) where the fine soot is used in combination with iron waste (iron filings):

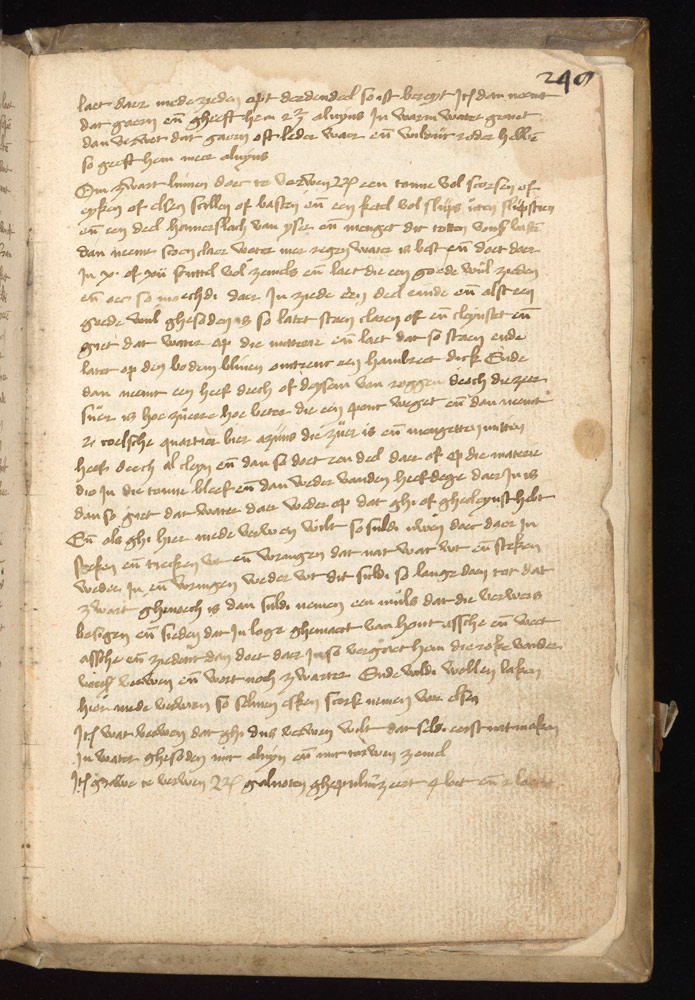

Another on black color. Take white incence and pound it and take a peck[51] and turn it upside down and ignite it and take a feather and brush the soot off and take filings of iron and put into water and stir through and through.[52]

These links between artisanal and domestic sites of colourmaking and sourcing, and the interwoven colour practices of dyers, painters and other artisans, became a recurrent topic of interest in our further explorations of historic black colour technologies – as did the proficiency of artisans in reusing what we would call today ‘waste’ products. Iron filings, for example, appear frequently in recipes for black dyeing, like this one in a late medieval manuscript (c. 1350) that lists similiar iron waste products in a short Dutch recipe for a vat to dye felted hats black with the bark of alder trees, gallnuts, iron filings and the iron swath that accumulates around grindstones:

Another to dye a felted hat black. Recipe aldery bark and filings of iron and the swath from grindstone and the galls boiled together. Herewith one dyes hats black.[53]

A German recipe for ‘A good hat colour’ (Farbbüechlin, codex 431, fol. 18r-20r) to ‘revive’ the faded blacks of hats and garments, like the one below reminds us that textile dyeing was at that time part of daily household activities, where colour knowledge was shared and practiced in domestic contexts (see the essay by Paula Hohti in this book).[54] It comes from the Farbbüechlin, a little handwritten recipe book ‘of many a colour for wool, linen, and garments’ dating from the second half of the sixteenth century (with later additions).[55] The Farbüechlin is described as a special kind of “do it yourself” manual, in an excellent German edition (2012) by Renate Woudhuysen-Keller, who has reworked many of its recipes; she published the complete transcript, together with her reconstruction trials and observations.[56] There, we find instructions for

[A] good hat colour with which one can dye the old hats or other formerly black faded garments nicely black again. Take aldery bark, do not remove the outer black bark, but take the outer and inner bark, cut very small, put a layer of bark at the bottom of the kettle, and on top a layer of swath. And on top of the swath a layer of old hats or other old woolen garments, but then a layer of aldery bark, and on top, though, swath and then on top of the swath a layer of old hats, or old faded black woolen garment, and so on layer on layer, do [that] until the kettle is getting filled, but watch out and take good heed that the hats, or the woolen garments are not laid too close to the sides of the kettle, that they do not touch the sides of the kettle, otherwise the hats, or the garments, can get burnt on the kettle. Then pour fresh spring water over it so that it stands two fingers above the material, hang it above the fire and let it boil for about an hour together, then remove the kettle, take the old hats, and the garment out and rinse well with fresh running water, wash and clean it from the swath, and other impurities, so you will have a nice black. That is when it is a woolen garment, because the linen cloth does not take on this colour. Note: Prior to boiling them in the kettle, you need to clean the hats or what is dirty, washing them carefully in strong cold lye and only then you can boil or dye them black, as told above. You can also use the blue dyewood [Praesentz] color when it is exhausted, and when it does not dye blue anymore, to black-dye old woolen hats, and formerly black, faded woolen garments. But you need to add vitriol to the exhausted dyewood color and boil the vitriol in it and only then dye the old hats or formerly black faded woolen garment in it, dye it warm, too, and it will become a nice black. [57]

The visit to the bread oven at the artists’ farm evoked pigment recipes in more ways than one. Bread dough also appears as an ingredient in a recipe for black-dyeing in a fifteenth-century miscellaneous manuscript compilation, including alchemical, medical and artisanal recipes (Ms. 517, fol. 248r), today in the collections of the Wellcome Library in London.[58] The recipe ‘Om zwart linen doec te verwen‘ (‘To dye black linen cloth’) (MS 517, 248v), written in a Middle Dutch hand, mentions the use of (gone off?) rye sourdough, ‘the sourer the better’ and ‘bier aziins‘, probably referring to beer that is left to ferment, turning sour over time.[59] It also calls for (wheat) bran, pieces of grain husk separated from flour after milling, barks from alder or oak trees and common ‘waste products’ from a smithery or pre-modern domestic environments: a kettle filled with swath from the grindstone and a part of the oxidized fine particles (hamerslach) that come free when iron is forged on an anvil:

To dye black linen cloth

Recipe one vat full of barks from oak or aldery skin or rind, and one kettle full of swath from the grindstone, and one part fine iron oxides (hamerslach), and mix this with the earlier mentioned cloth, then take clean, clear water, but rain water is best, and add to it .x or xii scuttle of bran, and let this boil for a good while, and in the same way you have to boil in it a part of bark and when it has boiled a good while, let it clear well or cleanse it, and pour the water on the material, and let stand like this, and let it rest on the bottom about a hand’s breath thick.

And then take a sourdough or the dough of a rye sourdough that is very sour, the sourer the better, that weighs a pound, and then take 1. Cologne quart beer vinegar [coelsche quartier bier aziins] that is sour, and mix it well with the sourdough, and then you put part of it on top of the material that remained in the vat, and then add to it again from the sourdough, then you pour the water back in that you had cleaned off.

And if you want to dye with it, you will push your cloth in, and take it out and wring it, and you will do this until it is black enough, then you will take madder root (muls) that dyers use, and boil it in lye made of wooden ashes, and potash, and while boiling it, the smoke of the earlier mentioned dye diminishes, and it gets even blacker. And if you want to dye with it woolen broadcloth, you will take ash bark for alder. To dye another one you want to dye, you need to wet it first in water boiled with alum and wheat bran.[60]

Another recipe for an alderbark vat written in a mix of Latin and the German vernacular around 1500 mentions where domestic dyers can source suitable iron waste like the swath from the harnasser (‘harnasse-maker’),[61] swertfeger (‘sword/blade maker’)[62] or slosser (locksmith) (Liber Illuministarum, fol. 198r):

Take a vat and half-fill it with aldery bark.

[Marginal note] Black. Take a bathing tub full of swath from the harnass maker or sword maker and pour it onto the bark, then take also two scuttles full of fine iron oxides [Hammerslag] or iron filings from the locksmith and pour these, too, onto the bark. Pour water on top and close [the vat] securely. And after standing for 6 weeks, take the old bark out, add new [bark] and let it stand again. The thicker it gets the better.[63]

Recipes for various alder bark vats for black dyeing are abundant in surviving late medieval and early modern sources, published in modern editions.[64] The chemistry of this colouring process has been described frequently, but alder bark vat recipes have rarely been studied or reworked in detail.[65] At Jongstra’s farm many of the ingredients could be sourced quite easily from the surroundings, giving us a sense of how these colour-making practices were embedded in socio-material settings in the past. The artist was able to set up a couple of large vats outside, following the sixteenth-century recipe instructions, just as we might imagine they had been kept by premodern rural households for domestic dyeing.[66]

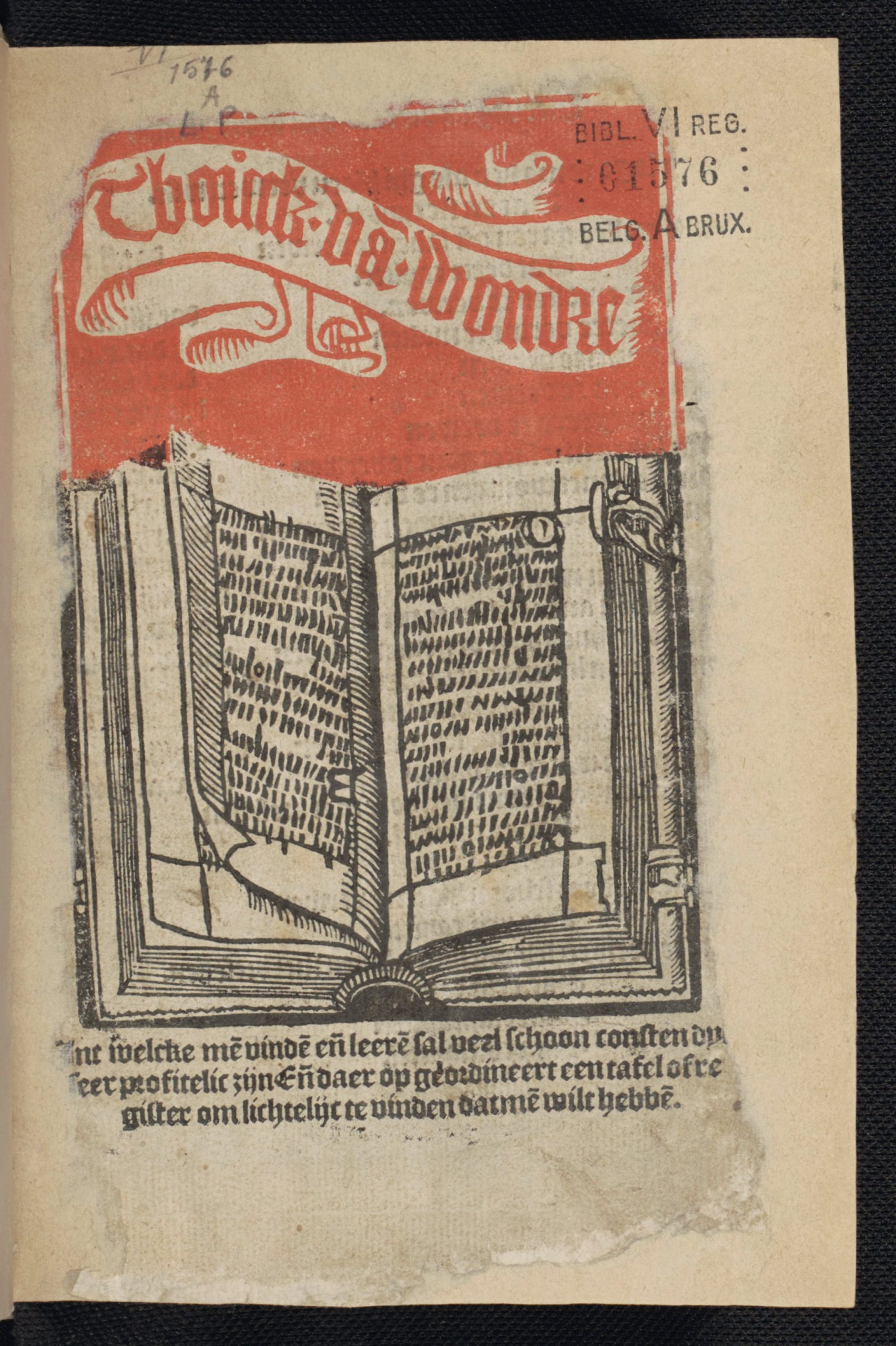

Chemically, these dyes are today characterized as iron-tannin complexes. With iron-tannin dye technologies, often used in combination with metal salts, light-fast dark shades can be attained, ranging from greyish and brown tones to bluish black. Widely known in the Middle Ages, this colour knowledge was likely transmitted orally, but also by manuscript and print in numerous recipes showing a great variety of dye procedures. The first known Dutch printbook with dye recipes was published in the Burgundian Netherlands: Tbouck van Wondre (The Book of Wonders, Brussels 1513, reprint Antwerp 1544). It presents a range of ‘wondrous’ colour transformations with many an ingredient abundant in early modern housholds and craftsmen’s workshops, including four recipes for black-dyeing wools, linen, silks, and velvets (swert lakē, lynwaet, side lakē of fluweel) that call for rye flour, a herring vat, and ‘schoenmakers swert‘[67] (shoemakers’ black) among others.[68] Advertised by the printer as a book ‘in which you find and learn much about the fine arts that is very profitable’,[69] it also includes a recipe to re-dye black silks and damasks ‘that have lost their colours’ in a dye bath of oak barks, promising to make them again ‘alderswerste‘ (the blackest black).[70] Other recipes describe the continuous reuse of alder bark vats that need to stand for weeks or months before the liquid is ready to use for black dyeing. After the liquid is tapped off, fresh water is again added on top of the alderbark iron waste mixtures and left to stand until needed. Also, the water from rinsing black dyed cloth is collected and added to the vat again, suggesting earlier economic imperatives and sustainable waste management strategies.[71]

A recipe for an alder bark vat with layers of swath and vitriol in the Italian dyers’ manual, The Plictho, describes this reuse in the recipe ‘A tenzer panno negro‘ (‘To dye woolen cloth black’). The recipe (discussed in greater detail in the essay by Natalia Ortega Saez and Vincent Cattersel and shown in the short film Reworking a ‘Lasagna’ Recipe from the Venetian Plictho (1548)), both in this book) ends with the sound advice: ‘and what remains do not throw away because it will be excellent to dye in the future because it is better than the first’.[72] The advice to reuse an exhausted blue dye bath for black dyeing with the addition of metal salts (vitriol) is similar to recipes found in a slightly later Dutch print manual, Een cleyn Verff-boecxken (1638)[73] including recipes for black-dyeing wool stockings for which the dye baths (sop) can be recycled (see the essay by Art Gaibor Proaño and Chrystel Brandenburgh with the short movie Reworking a black dye recipe from ‘Een cleyn Verff-boecxken (1638)’).[74]

In preparation for the Burgundian Black Collaboratory in January 2019, one of us (Jenny Boulboullé) met with Natalia Ortega Saez, an expert in historic black dyes and lecturer in textile conservation and restoration at the University of Antwerp, in mid-December [75]. For her disstertation, Black dyed wool in North Western Europe, 1680-1850: The Relationship Between Historical Recipes and the Current State of Preservation, Ortega Saez had undertaken a detailed study of historic technologies for black dyeing in order to gain a better understanding of the deterioration observed in preserved historic textiles.[76] Though her dissertation focuses on textile artifacts that have survived from the late seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, her research dates further back to dye technologies of the Burgundian-Habsburg Netherlands. I was accompanied by Suzanne Bul, a graduate student from the Technical Art History Master program at the University of Amsterdam, who assisted me with the workshop preparations. Bul and I were both invited to apprentice with Ortega Saez in her teaching laboratories. In contrast to us historians, Ortega Saez is also an experienced dyer, who had studied and taught dye techniques with botanical colourants for years. The aim of this preparatory workshop was to engage hands-on with a number of historic black-dye recipes we had brought with us to the teaching lab. Over the previous weeks Bul and I had been compiling a recipe collection focusing on pre-modern black-dye technologies (c. 1350-1700).[77] From the many recipes Bul found, we had made a preliminary selection to rework in the lab, trying to use ingredients similar to those historically used. The first day we spent in the lab close reading the recipes. We learned from Ortega Saez how to read a historic recipe with an eye for identifiable and comparable units of information — highlighting mentioned ingredients and measurements in weight and time when given, thus being able to group recipes into ‘families’ based on ingredient use and on chemically explainable colour transformations that can be derived from this information.[78] In this reading mode, we paid close attention to historical names for colours and ingredients and their etymologies. We shared a keen interest in these complex historical etymologies but also became aware of different modes for reading recipes. As a philosopher and historian trained in close reading methods and source criticism, I was not used to distilling information from historic texts in this manner. This incited some interesting conversations about recipe reading methods and made us aware that taking time for close readings that account disciplinary differences, is crucial when planning interdisciplinary reworking workshops.

Ortega Saez had distinguished three different types of black dye technology in her dissertation, two of which were certainly known and practiced in the Burgundian Habsburg-Netherlands in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.[79] We decided to rework recipes from each type to better understand how dyers managed to attain black shades in the past. After we had made a final selection, we discussed how we could translate the recipe texts into feasible working protocols, taking into account that we had only one working day in which to conduct the dye experiments, once we had gathered all necessary materials.

The following discussion focuses on the most expensive method of black dyeing during the Burgundian period, a time-intensive two-stage dye procedure with blue and red plant dyes.[80] It was used for the finest broadcloth for the making of precious textiles intended for year-round use and frequently adapted to the latest fashion, like the precious black dresses made for the Duke of Burgundy and his entourage.[81] This costly black-dyeing method is evidenced in decrees, ordinances, and guild regulations of Flanders’ larger textile centers prohibiting the use of other black dye technologies or additives for high-quality wools up to the seventeenth century.[82] Willem L. J. De Nie mentions in his standard work on the development of the textile dye practices in the Northern Netherlands (c.1300-1900) that this late medieval dye had gained fame as ‘Flemish black’ (‘vlaamsch zwart’) in the seventeenth century, perhaps indicating that it had first been produced on a large scale in Flanders’ textile centers.[83]

Surprisingly, Ortega Saez had found no black dye recipes for the expensive two-stage dye technology in the historic sources she consulted for her dissertation; the sources only mention recipes for other black dye technologies and for plant-based blue and red dyeing, but no recipe for overdyeing a blue ground with red to attain black.[84] In a German edition of a small, handwritten recipe book, The Farbbüechlin, or colour booklet, dated to the second half of the sixteenth century, Bul had found one recipe entitled ‘Kostlich Schwartz färben’ (Codex 431, fol. 30v) a title likely alluding to a costly and exquisite black.[85] The recipe gives a condensed description of the overdye procedure:

To dye costly/excellent black

So take the blue, cook it in alum and then pass it through the red, in this manner it becomes a good black, as good as the others.[86]

The brevity of this recipe might indicate that the writer had already been less familiar with this method when noting it down in the sixteenth century, as the most costly blue-red overdye technique saw a rapid decline towards the end of the sixteenth century. [87] Historically it would have been most likely that the blue ground of Burgundian black wools was dyed with woad plants (Isatis tinctoria L.)[88] growing in Europe or a mixture of woad and imported indigo pigment. Indigo (Indigofera tinctoria L.) had been known in Europe since ancient times but only imported on a large scale from the sixteenth century onwards with the rise of the global sea trade and the expansion into the Americas (see Jo Kirby’s essay elsewhere in this book). Vat-dyeing with indigo-yielding plants is a very complex, labour- and time- intensive process.[89]

Different cultures for processing the plant matter of indigo-yielding herbs into tradeable products developed around the world. Indigo imported from Southeast Asia reached the European trading centers as a highly concentrated indigo pigment — long before the indigo trade intensified through the new sea routes opened by Christoper Columbus and Vasco da Gama and before the large-scale indigo trade with the Americas started in the sixteenth century.[90] Woad, a plant growing in Europe with lower colour concentrations, was further processed and refined into fermented and dried woadballs made from macerated pulp to improve its dye quality. Up to the sixteenth century, woad was used first exclusively and then still predominantly, in combination with only small amounts of indigo pigment, in European dye industries when dyers were making blue fabrics.[91] Despite these historically significant differences, the blue colouring matter of both indigo-yielding plants, woad, and indigo, is chemically identical: indigotin.[92]

Given our tight schedule of, we decided go for the quickest possible way to make a blue ground colour with indigotin, the colouring matter that would historically be most likely present in high-quality black dyed textiles from the Burgundian-Habsburg period.[93] Ortega Saez had a quick and easy recipe at hand for an indigo dye vat, with additions of modern-day chemicals (sodium hydroxide and sodium dithionite) that significantly accelerate the required reducing fermentation process for blue dyeing.[94] In this way, the labourious process of indigo vat dyeing could be translated into an instant blue-dye laboratory procedure, using synthetic indigo pigment and chemicals to produce laboratory prepared indigotin-dyed textiles. We could use these blue grounds then for further dye experiments to attain the famous ‘Flemish black’. Ortega Saez deliberately chose to use the term ‘laboratory-prepared black woolen samples’ in her dissertation, to lay the emphasis on the site-specific making of the lab-born swatches she created for her study of deterioration effects in historic, black-dyed textiles.[95]

To be historically more ‘accurate’ we would have preferably used a natural indigo pigment, purchasable from ‘historic’ art materials suppliers, like the one Ortega Saez used for her dissertation experiments, however, chemically and in terms of working protocol, the use of plant-based natural indigo would have made no difference. From the perspective of a chemist, the resulting blue wool fabric — our blue ground for the historic two-stage dye process for attaining black — is comparable to historic dyed textiles: in both cases the blue is derived from indigotin.[96]

Our reading of the brief recipe, starting with the words ‘So take the blue’ (‘So Nim dz blaw’) thus focussed on a chemically identifiable colouring component that would be historically plausible. With this focus on detectable colouring matter we translated the historic recipe into a feasible working protocol: within a few hours we could dye a blue textile with modern means and methods.[97]

The shift in location — from reading site to reworking site — was important for our historical and material-technical research: bringing the sixteenth-century recipe text for Kostlich schwartz färben into a modern laboratory prompted us to reflect on hands-on knowledge of early modern blues and on site-specific recontextualizing of the pre-modern colour concept for ‘blaw‘ (blue) embodied in our historic recipe text.

The reworking in the lab was product-oriented: we wanted to make a blue-dyed textile that could function as an underground in further historic black-dye experiments. This recontextualisation in the modern laboratory made practical sense, as our chemical ‘translation’ resonated with the affordances of the environment; it also made sense from the perspective of a professional dyer, searching for the most economic and efficient dye technologies. An experienced dyer, Ortega Saez had the necessary experience and chemical expertise to safely guide us through the working protocol designed to be performed within one afternoon, and all necessary chemicals as well as the protective gear required to handle them were ready-to-hand at this site. The lab photo report shows that we used small pieces of woolen fabric and dyed these in small cooking pots. It documents the sequence of hands-on handling performed, weighing the ingredients, stirring powders with water into paste, pouring the paste and powders into a pot, stirring again, observing colour change, wetting fabric, lowering the fabric into the pot, stirring, taking the fabric out of the pot, airing the fabric and hanging it on a washing line to dry.

As historians with no dye experience we were amazed by the colour change, witnessing how our white woolen fabric came out of the dye vat and turned from very light green into indigo blue in the air — a colour transformation known since ancient times that has lost nothing of its magic, as other reworkings, reconstruction reports, and reactions of students show.[98] The rest of the handlings in this dye experiment felt more familiar from laboratory seminars and home cooking.

In retrospect, this very process — bringing a recipe text from the archives into the lab, reading it in the context of a laboratory work setting that allowed us to recontextualize the ‘blue’ in our recipe and to make it into a reworkable colour — generated so many important questions about historical colour knowledge that would not have been raised in a library reading room. This became even more apparent when we recontextualised our historic recipe texts again by bringing them from the lab to the artists’ studio. So, after we learned how to translate historic recipes — with rich, often unfamiliar, pre-modern colour connotations — to a modern-day laboratory site, we then started to prepare for our next reworking in a rural environment, more similar in some aspects to the working environments of premodern dyers.

Back to the Artist’s Studio (Seasonality and Temporality)

During my first visit to Claudy Jongstra’s studio in October 2018 the idea was born to organize an expert workshop onsite at her studio/farm in Friesland. With the planned opening of the exhibition in June 2019 in mind, we decided that this workshop had to take place as soon as possible and started to plan a three-day workshop in the third week of January 2019. Being used to working on reconstruction experiments in a laboratory setting, I did not think too much about the consequences of planning a black-dye workshop with natural dyes in the middle of winter. In practice, working onsite on Jongstra’s farm, we ran into many challenges. Through the challenges and failures, though, we were able to glimpse pre-modern colour worlds that would not have revealed themselves to us in laboratory settings. Colouring with plant-based dyes, like other agricultural activities, was a seasonal business, structured by harvest time, the rhythm of night and day, working with the warmth of the sun, and at paces unfamiliar to most modern scholars and artists.

As Art Gaibor Proaño, organic colour specialist from the Research Laboratories of the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, put it: ‘I have learned so much more about colour technologies during this workshop, seasonality, for example, I had never even thought about this seriously before… I gained an appreciation of the significance of seasonal aspects and a novel admiration for the dyers’ work and for historic dyed textiles’.[99] He adds that having to work with seasonal challenges generates different and new sets of questions; for example, a much-discussed question when working with historic recipes in the lab is the choice of water (tap water or demi water) when the recipe calls for ‘rain water’, ‘clear water’, or water from a river or a ditch, illustrating the tension between the wish to keep the controllable parameters as narrow as possible in a laboratory experiment and the researcher’s intention to rework historic recipes with ingredients that are as historically ‘accurate’ as possible. Through this experience we and our collaborators Gaibor Proaño and Ortega Saez, became, for example, sensitized to the rich information on seasonal matters codified in colourmaking recipe texts, that has not caught much of our attention when reading and reworking recipes in lab experiments before.[100]

Access to natural resources mentioned in recipe texts was in many cases much easier in our onsite planning. For the workshop, Jongstra and her team made sure, for example, that enough water butts filled with rainwater were available for use, standing outside the greenhouse where the dye workshop was going to take place. However, the use of these rainwater supplies when frozen in winter added an unexpected laborious dimension to the dyers’ work.

Back to the Archives (The Secret of Burgundian Black)

In preparation for the Burgundian Black Collaboratory, we intensified our search for historic recipes that would testify to the art of black dyeing with red and blue. For the Burgundian-Habsburg period, dyers’ colour knowledge had predominantly been deduced from archival materials, such as decrees, ordinances, and guild regulations of Flanders’ larger textile centers; recipe literature on dye technologies are seldom cited, as Netherlandish practical and technical writings on dye technologies in the vernacular dating from before 1600 are scarce.[101]

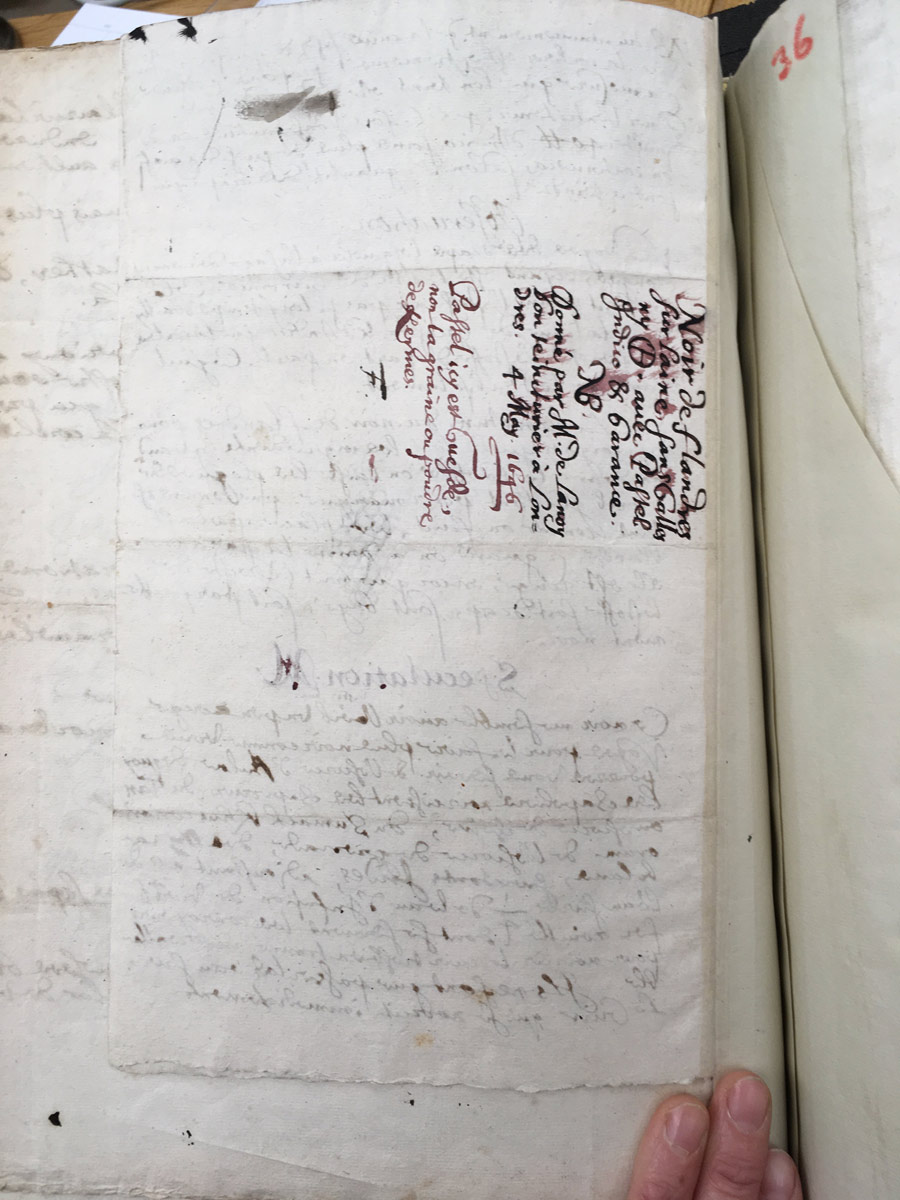

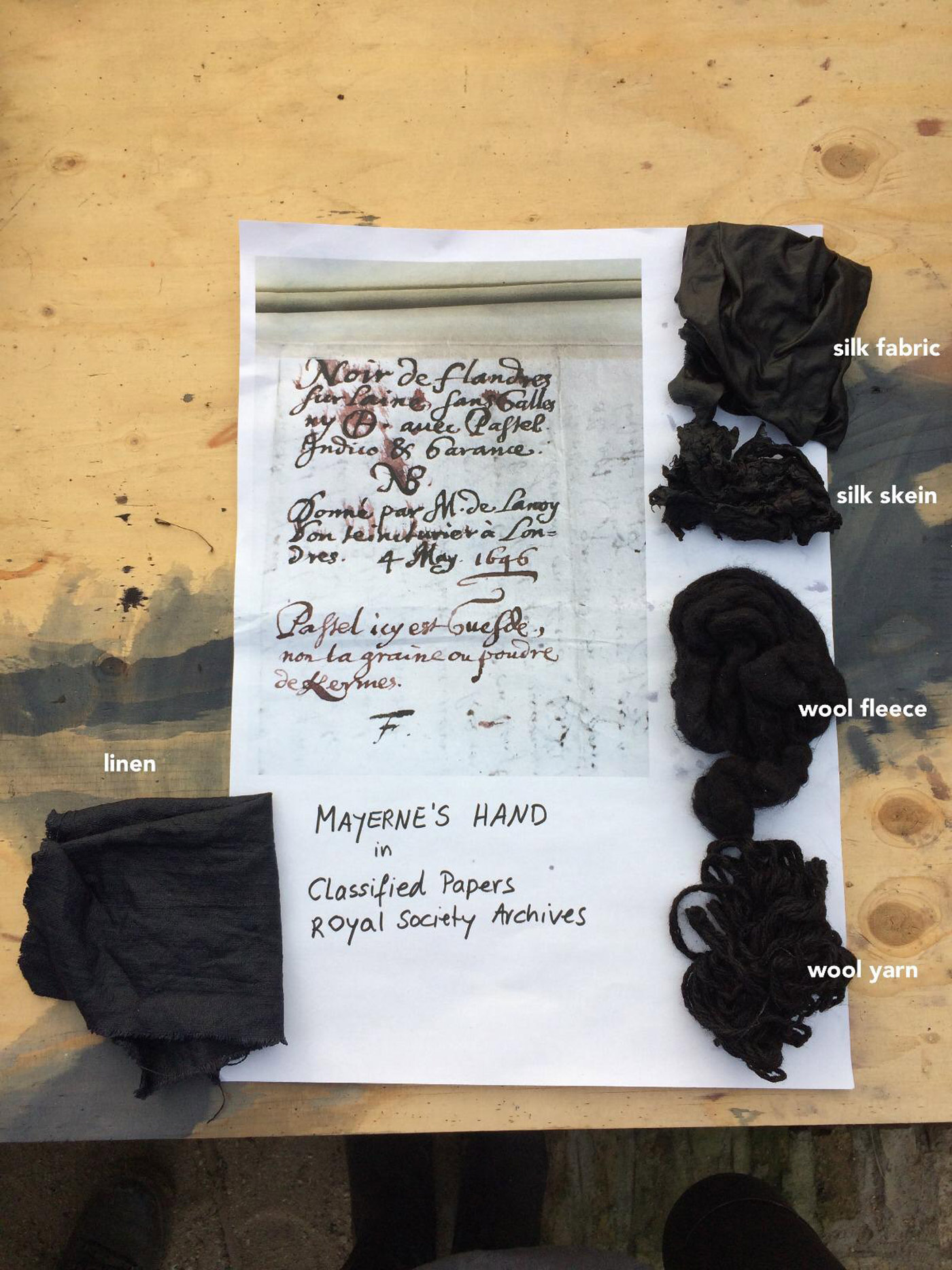

The recipe one of us (Jenny Boulboullé) found for Noir de Flandres (Black of Flanders, ClP/3i/34) in the Archives of the Royal Society in London provided a more promising starting point than the German recipe for Kostlich schwartz.[102] Though dating from the mid-seventeenth century, it explicitly refers to the Flemish black that the textile centers under Burgundian-Habsburg reign had been famous for throughout Europe.[103] This recipe for dyeing Burgundian black came down to us as a true secret, drawn from the mouth of a ‘bon teinturier‘ (good dyer) and recorded in ink on a bifolio of paper. It must have been folded up into a neat small package when it reached its recipient, the famous court physician Sir Theodore de Mayerne (1583-1655). Mayerne, a French-speaking Huguenot and well-known benefactor of the Flemish arts and crafts of his time, is today renowned for his keen interest in the colour knowledge of artists and artisans.[104] When the dyer’s secret came into Mayerne’s hands, he must have labelled the folded bifolio on its verso, giving the recipe the alluring title ‘Noir de Flandres‘ and noting down its main ingredients. He also recorded the date, place, and source of this precious piece of colour knowledge:

Black of Flanders

on wool without Gallnuts

or [symbol for] vitriol. with Pastel

Indigo & MadderNote well. [N[ota] B[ene].]

Given by Mr. de Lanoy

good dyer at Lon=

don 4 May 1646

Pastel here means Woad,

not the ‘graines’ or powdre of Kermes.

Fr.[105]

When stumbling upon this recipe in the archives of the Royal Society in the autumn of 2018, Boulboullé immediately recognized Mayerne’s idiosyncratic hand and his penchant for red ink to mark important bits and pieces of information. This recipe had not made it into the codex that Mayerne is today famed for among conservators and technical art historians: the so-called Mayerne Manuscript (Ms Sloane 2052) with an extensive collection of colourmaking recipes that was neatly compiled and bound after his death in 1655 when it came into the possession of Sir John Sloane (1753-1837), the founder of the British Museum in whose collections it survived the ravages of time.[106] The Noir de flandres recipe, on the other hand, probably entered the archives of the Royal Society in a paper wrapper, comprising several colourmaking recipes formerly folded into thirds and labelled like this one by Mayerne, where they are now bundled and preserved with other early unpublished papers of the first fellows of the Royal Society.[107]

Far from being comprehensive step-by-step instructions or self-standing operational rules, historic recipes can often better be described as ‘aides-mémoir’ with much relevant information implicit or assumed.[108] The inner pages of the bifolio show quite detailed technical descriptions, more information on trading details and amounts of materials, and additional speculations and observations, written in different hands.[109]

Dated to 1646, the writers recorded a dye process that could already be considered ‘historic’ at the time the recipe was collected. By the seventeenth century the strict regulations for the two-stage black dyeing with a blue ground, top dyed with madder red, and no further additives of tannins and metal salts, enforced by guilds since the Middle Ages, had largely been lifted; in Mayerne’s time Europe’s textile centers saw increasing imports of indigo pigment and new dyestuffs from overseas, enabling dyers to experiment with faster and more economical procedures for dyeing black shades.[110]

On first sight, Mayerne’s brief note on the verso of the bifolio, cited above as fol. 4, appears similar to the short German recipe for Kostlich schwartz that describes a blue-red dye technique for attaining a ‘black as good as all the others’. Mayerne is, however, much more specific in his description of the black of Flanders: he mentions that this black is dyed on wool (‘sur laine’), and lists not only the required ingredients, but also those that should not be used (‘without gall nuts and no vitriol’), alluding to the prohibitions enforced by guild regulations in Flanders’ textile centers up to the seventeenth century. Except for black, Mayerne’s recipe gives no colour names, but specifies the use of pastel, indigo, & garance for this dye technology. The ‘blue’ and ‘red’ from our previous recipe are now identified as specific plant dyes: pastel refers to dyestuff made from the woad plant (Isatis tinctoria L.) and indigo most likely refers to imported indigo pigment (Indigofera tinctoria L.) that was added to the woad vat. Garance is French for madder root (Rubia tinctorum L.), and, as Jo Kirby mentions in her essay in this collection, is one of the oldest plants used for red dyeing in Europe.[111] The black thus attained was also known as madder-black.[112]

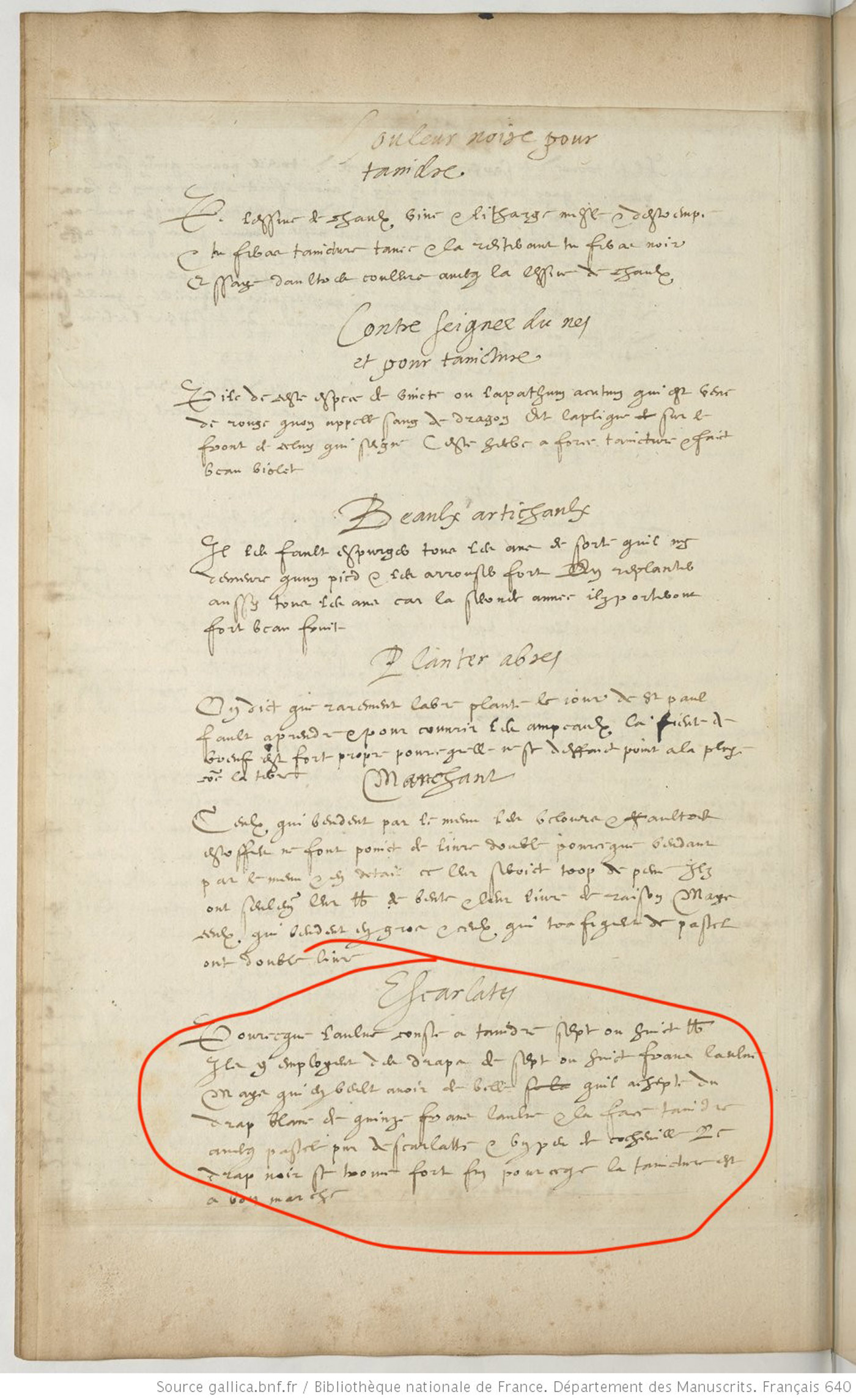

We also found a mention of the costliness of black textiles dyed with blue and red in a late sixteenth-century French recipe book, BnF Ms Fr. 640, in an entry on ‘Scarlets’ on fol. 38v, that mentions the expenses for red dyeing. The writer gives advice on how to dye a beautiful black with pastel woad, scarlet red, and the addition of ‘a little bit of cochineal’ (an expensive insect dye), while saving costs on dyestuff by using cloth that ‘is very thin’:

Scarlets

Because one aulne costs seven or eight lb to dye, they use cloths worth seven or eight francs an aulne. But whoever wants something beautiful should buy white cloth worth fifteen francs an aulne & have it dyed with pastel woad pure of scarlet & a little cochineal. The black cloth is very thin so that the dyeing is inexpensive.[113]

It remains puzzling, as others have noted before, that the precious blue-red-black dye techniques are not mentioned in the Italian Plictho, the earliest known, extant printed book on the art of dyeing published in 1548.[114] A mention of this overdye method can, however, be found in a roughly contemporary Italian publication, Leonardo Fioravanti’s Dello specchio di scientia universal (On the Mirror of Universal knowledge) first published in 1564, a true longseller that saw many editions over the next hundred years and was soon translated into French and German.[115] Fioravanti does not provide us with a recipe, but his account is of special interest as he was known to describe many crafts and trades from first-hand observations, as did Mayerne and his informants, and like the anonymous writer of the French manuscript BnF Ms. Fr. 640:[116]

But the good dyer needs to know all the intricacies of his art, as this one, that one dyes the wool with woad, and on top of that one gives red [madder], and this dyeing will give a colour of the finest black.[117]

Fioravanti differentiates this ‘finest black’ from another way of dyeing ‘a very black colour’ with galls and vitriol.[118] This distinction corresponds with Mayerne who defines the Noir de Flandres as being dyed with woad, indigo, and madder, but without galls and vitriol.

Mayerne, Fioravanti, and the anonymous author of BnF Ms. Fr. 640 all seem to have held a much greater appreciation for the authoritative method of black dyeing with woad blue and madder red than the writer of the above-cited German recipe. On the very bottom of the first page of the bifolio, underneath the dye instructions ‘pour teindre noir de flandres‘ (‘to dye black of Flanders’), we find a note in Mayerne’s hand, promising those who try this recipe: ‘you will have a perfect and durable black’ (‘Vous aurès un noir parfaict et durable’.) With this heartening outlook we started our preparations for dyeing the Black of Flanders in Friesland, together with the artist, her team, and the group of international experts invited to the Burgundian Black Collaboratory in January 2019.

The Burgundian Black Collaboratory

‘This is madder. . . . It is the root that gives the colour. It is actually one of the basic colours of the very deep Burgundian Black. It is a composite colour, the black. It is made with walnut, madder, indigo, and if you want it supreme, you add a final layer of cochineal. If it were a wine, you might describe it as a claret, full-bodied, deeply matured, with yet another year, and another season. It’s all in there’. — Claudy Jongstra, 2020.[119]

In this interview, recorded in 2020, the artist paints the colour ‘Burgundian black’ in words as a composite of basic hues, built up of different layers that give the colour a depth and complexity which she compares to a glass of the finest French wine, ‘full-bodied and well-matured’. The comparison beautifully illustrates how our focus shifted from chemically identifiable colour substances to dye plants and to the labour- and time-intensive processes of botanical colourmaking. In an earlier interview during the Burgundian Black Collaboratory in January 2019, Jongstra explained that in the palette of natural colours with which she works, blacks were still a challenge (see Back to Black exhibition movie by Joshua Pinheiro Ferreira above). On blues she told us that they had started to experiment with growing their own indigo-yielding plants, Japanese indigo and woad.

Perhaps the most challenging was the Noir de Flandres recipe for which we needed to prepare first a blue ground, dyed in a woad-indigo vat, which was then — in a second step — top-dyed with a red madder mordant dye. Our recipe specifies ‘To dye noir de flandres (which is black made of madder) you need to make first a dark blue (brun bleu)’; further on, it mentions amounts of woad (1000lb), indigo (40lb) and water (400 barrels) required for a woad vat (‘cuve de guesde‘) on a scale that was likely meant for professional dyers, but this recipe provides no further information on how to set up the woad indigo vat.[120]

Woad is one of the oldest known dye plants and its use for dyeing has a long history in Europe dating back at least 3500 years, as a unique finding of blue dyed textiles from the Bronze Age (1500-1100 BCE) and Iron Age (850-350 BCE) in the salt mines of Hallstatt in Austria show.[121] Woad was cultivated extensively in Europe until the end of the sixteenth century and then practically disappeared. Only recently have countries with a long cultivation history of woad (Germany, England, France, and Italy) restarted to grow woad on a much smaller scale.[122]

In the Netherlands, Jongstra has now started to actively reintroduce woad cultivation into Dutch agriculture with biodiversity projects in collaboration with farmers, museums, and landscape management agencies. She also set up an initiative in 2020 for the preservation and protection of indigenous dye plants, with woad as a pilot crop: The Community Seed Bank for Colour, an open source seed bank for historical dye plants.

Back in the summer of 2018 Claudy Jongstra and her team had harvested their first homegrown biodynamic woad (Isatis tinctoria L.). The leaves had been picked and processed by hand into fermented green woadballs, then dried and preserved.[123] But they faced a difficult question: how to get from colour plant to blue dyed textile? The workshop allowed us to rework historic recipes for woad-indigo vat dyeing with Jongstra’s masterdyers and to explore collaboratively under more rural conditions in a greenhouse with open fire sources how Flemish dyers in the past had worked with plant materials to attain the proper dark blue grounds required for black-dyeing. In the context of Jongstra’s working practice, how to dye a proper blue ground was not only understood as a question of technically and chemically understanding processes of colour extraction and light-fast textile dyeing, but also of indigo-yielding plant cultivation and plant processing, and colourmaking as a collaborative activity.

“Woad is more than blue.”[124]

One of our collaborators, Proaño Gaibor, organic colour specialist at the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, had earlier participated in an interdisciplinary research initiative that brought art and science together in a study of the already mentioned prehistoric blue dyed textiles found in the salt mines of the Austrian city of Hallstatt. The aim of that study was to produce replicas — with traditional methods — of the Hallstatt textiles for the Natural History Museum of Vienna, and as inspiration for contemporary applications.[125] To this end, the researchers studied prehistoric dyeing techniques, exploring blue colourmaking from plant cultivation to dye vat. Anna Hartl, who led the scientific research, said in an interview on their attempts to rework prehistoric dye methods in their research laboratory, for which they used woad crops planted on a plot at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna: ‘We started the development of dyeing processes with a literature search in ethnological and historical sources. One should not imagine experimenting as a linear process (read, dye, successful result) especially in the case of a fermentation dye process. It rather follows the principle of ‘trial and error’: read, try, fail, read again and ask questions, try again – till it finally works’.[126] She added that the exchange of practical experiences with artists and natural colourant professionals was important for that process.[127] Such insights were helpful as we developed colourmaking processes, and we were happy to draw on a rich body of literature on the woad plant and its dye — in particular on Hartl’s and several other studies that draw on experimental findings, reworking (pre)historic woad dye technologies.[128] These studies make clear the wealth of botanical colour knowledge that was present in Europe and exploited on a large scale up to the nineteenth century.

In contrast to the Hallstatt project, where archaeologists and conservation scientists focused on the extant textile artifacts as primary sources of prehistoric colour knowledge, we were able to draw on contemporary textual sources testifying to the expertise of past dyers. Our aim was not to produce replicas; we were process-oriented, as we tried to understand and actualize the botanical colour knowledge embodied in our premodern recipe texts.

The colour worlds emerging from premodern recipes resonated in different ways within the rural and artistic context in Friesland where Jongstra and her team had started to cultivate a form of textile artmaking as a holistisc project. Jongstra started decades ago to develop an artistic practice that fosters and feeds on an active awareness of the production cultures of the natural materials she mainly uses. She maintains for example an indigenous flock of the oldest breed of Drenthe Heath sheep and grows dye plants that have a long cultivation history in the Netherlands but have mostly disappeared from Dutch rural landscapes since the nineteenth century. The artist understands biodynamic and sustainable ways of farming, and the reintroduction of rare or forgotten sorts to ‘revitalize the local landscape from monocultural production toward a more diverse, inclusive, and ecologically-just model’ as key to her artistic practice and vision.[129] Colourmaking as a community-shaping activity, bringing the local expertise of farmers together with the expertise of international students and interns, has become an integral part of her work, as has the emphasis on attention to natural resources and skilled hand-labor. In this setting, questions arose about recipes as testimonies to plant-based colour worlds where chromatic expertise and colourmaking were closely interwoven with agricultures and particular socio-material environments.

Pastel Woad:

Mayerne describes Noir de Flandres not in terms of blues and reds, but in terms of pastel, indigo, and garance. He also added an explanatory note in his signature red ink informing the reader that ‘Pastel icy est Guesde, non la graine ou poudre de Kermes‘ (‘Pastel here means woad, and not the graine or powder of kermes’).