Bone is closely related to ivory, hartshorn, tusk and teeth materials, due to their comparable composition. As proven by archaeological excavations, these materials are remarkably durable and even survive extreme fires. They consist of organic components which are mainly collagen, and of inorganic mineral components, calcium hydroxyapatite with calcium and phosphor as major elements.[27] By complete combustion (burning), bones and related materials lose all organic components. Calcium hydroxyapatite remains, which is white of color (bone white). As a result of incomplete combustion (charring) most of the organic components are lost, but carbon is formed and re-crystallizes into graphite-like structures. Together with the inorganic calcium hydroxyapatite, which also abides high temperatures, these form bone black. The re-crystallization process (carbonization) of bone material starts above temperatures of 350°C, resulting first in brown-black colored products. From 600°C onwards, changes in the crystalline structure occur and the remaining material is deeply black colored.[28],[29] Charred bones, hartshorn and ivory are very hard, and require proper pounding first, and then grinding on stone slabs before they can be used as a pigment.

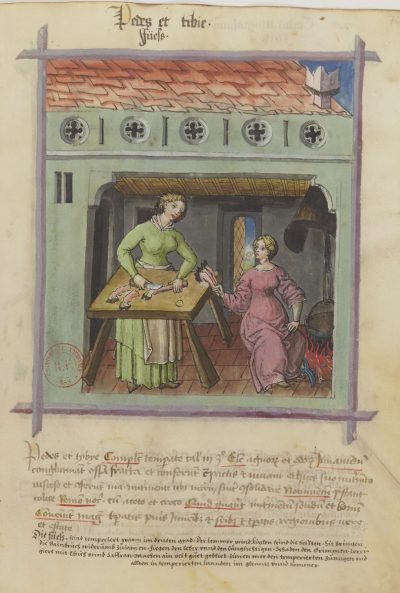

> Charred bone (spodium) Figures 26a, 26b, 26c Quote 14 / Recipe 10 RECONSTRUCTION Color sample 5

“Le meilleur de touts les noirs, qui s’estend le mieulx, & duquel mestnes on peult glacer, est le noir d’yuoire, ou d’os de pieds de mouton, lesquels se mettent par pieces dans vn creuset, qu’il fault bien couurir d’une tuile ou bricque, & luter les joinctures si exactement que rien no respire; le tout sec soit mis dans vn bon feu, par l’espace d’vne heure seulement, (aultrement les os pourroyent blancher), & ainsi soit bruslée la matière a parfaitte noirceur.” [30]

Bones were common domestic left-overs, as we learn from Cennini’s recipe for the preparation of bone white: “… take the bones of the ribs and wings of fowls or capons; and the older they are the better. When you find them under the table, ….”[31] Bone white, very closely related to bone black, is prepared by complete combustion, and was a conventional artists’ material in the fifteenth century. It served for instance as a coating of paper supports for metal-points, the dominating drawing material of the Burgundian period.[32] By excluding oxygen during charring, bone black could be produced, which around 1450 was considered “the best for illuminating”.[33] Care must be taken during charring that no oxygen reaches the bones, because in that case the combustion continues, the carbon reacts to carbon dioxide and the bone material turns white (calcium hydroxyapatite, bone white). This process can happen locally, usually close to the lid where air might enter (Fig. 26c). Such a side effect was well known, and is described by Mr. Mytens, Excellent painter, who recommends using sheep feet to produce bone black and warns about ‘bleaching’ in the above-quoted recipe.

Charred bones are mentioned under the term uulgariter Elpenswarcz (vulgar ivory black) in the Liber illuministarum to color beeswax black.[34] The late sixteenth-century author of MS Fr 60 refers to burnt bones of the feet of oxen as a black pigment, which according to him renders a blueish tone.[35]

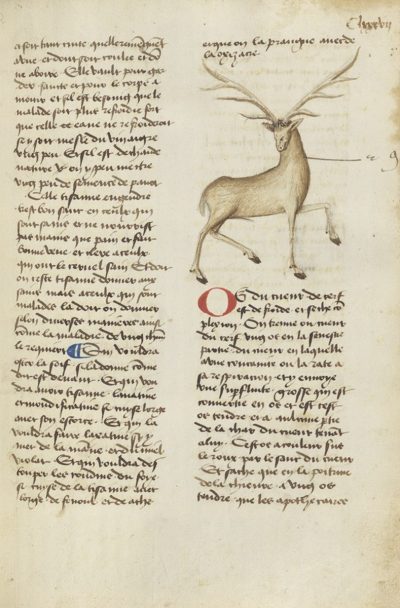

> Charred hartshorn (cornu cervi ustum) Figures 27a, 27b, 27c / Color sample 6 / RECONSTRUCTION

The antler of a male red deer, hartshorn, resembles bone in its composition and therefore its charred products are comparable to bone black. Reconstructions showed that hartshorn is extremely hard and sawing into pieces was necessary to fit them into a crucible. None of the consulted fifteenth-century sources contained a reference to charred hartshorn black, while several subsequent sources of the sixteenth and seventeenth century do mention it as a watercolor pigment. Hartshorn was obviously known in the Burgundian period; Liber Illuminarum refers to burnt hartshorn white, stating that it is comparable to lead white, but less white than burnt ivory.[36] It was available via the apothecaries, where it was sold as cornu cervi ustum.

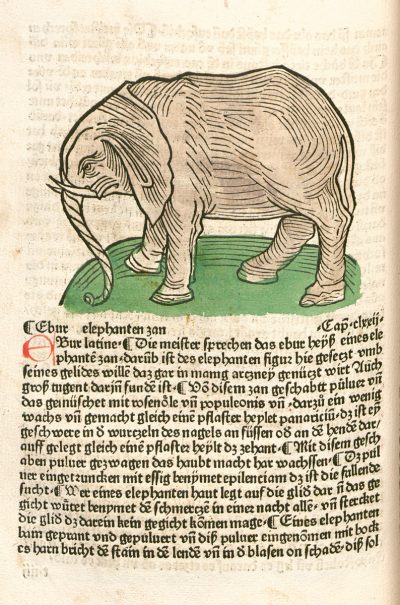

> Charred ivory (ebur ustum) Figures 28a, 28b Quote 15 – Recipe 11

“Schwartz in Schwartz malen oder zuschreiben. Meister Lucas Churfs.’ Mahler zu Wittem= / berg, hat under andern auch diss lob / gehabt, daß er den besten / Sammet soll gemalt haben, darumb daz er in schwarz / noch schwarzer, vnd auch allerschwarzst / hat mahlen können dem Thue allso. /

Nimb bei einem Compassenmacher 1 h. / helffenbeinen Abschnitten, thue es in / ein unverglest seidl hefelein, deckh ein / stürzlein darüber, verkleibs mit Leimen / auf das aller genaust, gibs einem / hafner, dass ers mit andern häfen / die er brent einseze, So es nun auß / dem offen wie andere hafen genommen / wurt, brich die stürzen herab, / heb dieselben gebranten stücklein / helfenbein auf, stoss in einem Mörsern / zu Puluer, wan du es zum schreiben / oder mahlen brauchen willt, reibs / unnder leinöl, so würstu sehen / daz es schwerzer ist dan kein schwarz.”[37]

Ivory black plays an important role as a black pigment until the nineteenth century. Ivory, the tusks of elephants, form black reaction products through charring, and white through complete combustion, as other bone materials do. Ivory black was a luxurious substance and was made from leftovers of ivory processing, like the ivory filings of comb and compass makers, [38] as described in the cited German recipe for a “black that is blacker than no other black”, referring to Meister Lucas, Kurfürstlicher Maler (most probably Lucas Cranach the Elder or the Younger) who was praised for painting the best velvets and the blackest blacks.

While many seventeenth-century authors mention ivory black as a watercolor, only a few earlier references exist. A fifteenth-century reference is found in codex Latinus Monacensis, including an indirect note to ivory black as a pigment, that mentions bone black as a substitute.[39] Surrogates for ivory are mostly ordinary animal bones. The tusks of mammoths, walruses[40], and the teeth of the sperm whale were used as well. Like bone, ivory is extremely durable. It was available in pharmacy shops as ebur ustum.

[27] According to Reitsma, ‘bone mineral’ is a hydrated hydroxyl-depleted carbonated calcium phosphate phase which is closely related to the geological hydroxyapatite, but has some important chemical differences. Reidsma et al. 2016. Charred bone: p. 283.

[28] Reidsma et al. 2016. Charred Bone: Table 1, p. 289 and p. 288 (XRD)

[29] Cruttenden. 2016. Fire & Bone. Poster.

[30] “The best of all blacks, which can be spread the best and with which one can even glaze, is ivory black, or that prepared from the foot bones of sheep. These, in pieces, are put in a crucible, which is well covered with a brick and the seams tightly sealed so that no air can penetrate, and put the whole thing on a strong fire, not longer than an hour, (otherwise the bones will bleach) and thus the mass is burned to a perfect black.” This quote refers to the preparation of sheep bone black for oil paint, but since the preparation method is the same for pigments for watercolors it is included here. In: Mayerne. 1620-46. Mayerne Manuscript, London, British Library, MS Sloane 2052: folio 93r. https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=sloane_ms_2052_f93r (transl. in Fels, Donald C., Lost Secrets of Flemish Painting: Including the First Complete English Translation of the De Mayerne Manuscript, B.M. Sloane 2052. Rev. ed. Floyd (VA): Alchemist, ed. 2010.

[31] Cennini. c. 1400. In: Broecke, Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: A New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription, 28-29 (Chapter 7); Merrifield. 1844. A Treatise on Painting. Written bu Cennino Cennini in 1434: Chapt. 7, p. 5

[32] Bone-white coatings were for instance confirmed to be present in the silver/goldpoint drawings by Jan van Eyck, and metal point drawings by Albrecht Dürer. Its abrasiveness was the precondition for drawing lines. Wallert et al. 2016. Notes on the Material Aspects (Metal Point): p. 25–35 and Reiche et al. 2001. Non-Destructive Investigation of Dürer’s Silver Point Drawings by SyXRF’.

[33] This is recorded in The Göttingen Model Book’. c. 1450. Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, MS. Uffenb. 51: fol. 6r. The internet-transcription reads ‘kyn swarz’ (Kienschwarz) = pine soot black. However, paleographically it is more likely that it means ‘byn swarz’ (Beinschwarz) = bone black and is included under this term here. https://www.gutenbergdigital.de/gudi/dframes/texte/frameset/indxmubu.htm.

[34] Liber illuministarum. 1450/1500-1512. Munich, Staatsbibliothek, MS. Germ. 821: I, 2v, 143r. In: Bartl et al. 2005. Der “Liber illuministarum” aus Kloster Tegernsee: 420-421 [1332, 1333].

[35] Recueil de recettes, after 1579, Paris, BnF, MS fr. 640: fol. 58v, 158v https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10500001g/f322.item, for translation see Making and Knowing Project. Smith et al., A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640 https://edition640.makingandknowing.org/#/folios/158v/f/158v/tc

[36] Liber illuministarum. 1450/1500-1512. Munich, Staatsbibliothek, MS. Germ. 821: I, 2v, 143r. In: Bartl et al. 2005. Der “Liber illuministarum” aus Kloster Tegernsee: 420-421 [1332, 1333].

[37] Mayerne. 1620-46. Mayerne Manuscript, London, British Library, MS Sloane 2052: fol. 130r, see: https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=sloane_ms_2052_f130r, last accessed 17 November 2020. The first German edition of this manuscript has numerous errors that have been corrected here. For instance, ‘kurfürstlich’ was wrongly translated as a surname ‘Cheufs’, missing the link to Cranach. Berger. 1901. Quellen für Maltechnik während der Renaissance und deren Folgezeit […] Nebst dem de Mayerne Manuskript: p. 304. The binding medium is linseed oil however, the preparation method of the pigment is the same for watercolors.

[38] Smith. 1687. The Art of Painting in Oyl: 18. https://archive.org/details/artofpaintingino00smit.

[39] Codex Latinus Monacensis. c.1464–1473. Clm. 20174. In: Neven. 2016. The Strasbourg Manuscript: p. 35.

[40] Hoogstraaten. 1678. Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst: p. 221.

Notes on the Material Aspects (Metal Point): p. 25–35 and Reiche et al. 2001. Non-Destructive Investigation of Dürer’s Silver Point Drawings by SyXRF’.

[1] Liber illuministarum. 1450/1500-1512. Munich, Staatsbibliothek, MS. Germ. 821: I, 2v, 143r. In: Bartl et al. 2005. Der "Liber illuministarum" aus Kloster Tegernsee: 420-421 [1332, 1333].

[1] Cennini. c. 1400. In: Broecke, Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: A New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription, 28-29 (Chapter 7); Merrifield. 1844. A Treatise on Painting. Written bu Cennino Cennini in 1434: Chapt. 7, p. 5

[27] According to Reitsma, ‘bone mineral’ is a hydrated hydroxyl-depleted carbonated calcium phosphate phase which is closely related to the geological hydroxyapatite, but has some important chemical differences. Reidsma et al. 2016. Charred bone: p. 283.

[27] According to Reitsma, ‘bone mineral’ is a hydrated hydroxyl-depleted carbonated calcium phosphate phase which is closely related to the geological hydroxyapatite, but has some important chemical differences. Reidsma et al. 2016. Charred bone: p. 283.

[29] Cruttenden. 2016. Fire & Bone. Poster.

[29] Cruttenden. 2016. Fire & Bone. Poster.

[33] This is recorded in The Göttingen Model Book’. c. 1450. Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, MS. Uffenb. 51: fol. 6r. The internet-transcription reads 'kyn swarz' (Kienschwarz) = pine soot black. However, paleographically it is more likely that it means 'byn swarz' (Beinschwarz) = bone black and is included under this term here. http://www.gutenbergdigital.de/gudi/dframes/texte/frameset/indxmubu.htm.

[34] Liber illuministarum. 1450/1500-1512. Munich, Staatsbibliothek, MS. Germ. 821: I, 2v, 143r. In: Bartl et al. 2005. Der "Liber illuministarum" aus Kloster Tegernsee: 420-421 [1332, 1333].

[34] Liber illuministarum. 1450/1500-1512. Munich, Staatsbibliothek, MS. Germ. 821: I, 2v, 143r. In: Bartl et al. 2005. Der "Liber illuministarum" aus Kloster Tegernsee: 420-421 [1332, 1333].

[37] Mayerne. 1620-46. Mayerne Manuscript, London, British Library, MS Sloane 2052: fol. 130r, see: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=sloane_ms_2052_f130r, last accessed 17 November 2020. The first German edition of this manuscript has numerous errors that have been corrected here. For instance, ‘kurfürstlich’ was wrongly translated as a surname ‘Cheufs’, missing the link to Cranach. Berger. 1901. Quellen für Maltechnik während der Renaissance und deren Folgezeit […] Nebst dem de Mayerne Manuskript: p. 304. The binding medium is linseed oil however, the preparation method of the pigment is the same for watercolors.

[37] Mayerne. 1620-46. Mayerne Manuscript, London, British Library, MS Sloane 2052: fol. 130r, see: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=sloane_ms_2052_f130r, last accessed 17 November 2020. The first German edition of this manuscript has numerous errors that have been corrected here. For instance, ‘kurfürstlich’ was wrongly translated as a surname ‘Cheufs’, missing the link to Cranach. Berger. 1901. Quellen für Maltechnik während der Renaissance und deren Folgezeit […] Nebst dem de Mayerne Manuskript: p. 304. The binding medium is linseed oil however, the preparation method of the pigment is the same for watercolors.

[37] Mayerne. 1620-46. Mayerne Manuscript, London, British Library, MS Sloane 2052: fol. 130r, see: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=sloane_ms_2052_f130r, last accessed 17 November 2020. The first German edition of this manuscript has numerous errors that have been corrected here. For instance, ‘kurfürstlich’ was wrongly translated as a surname ‘Cheufs’, missing the link to Cranach. Berger. 1901. Quellen für Maltechnik während der Renaissance und deren Folgezeit […] Nebst dem de Mayerne Manuskript: p. 304. The binding medium is linseed oil however, the preparation method of the pigment is the same for watercolors.

[37] Mayerne. 1620-46. Mayerne Manuscript, London, British Library, MS Sloane 2052: fol. 130r, see: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=sloane_ms_2052_f130r, last accessed 17 November 2020. The first German edition of this manuscript has numerous errors that have been corrected here. For instance, ‘kurfürstlich’ was wrongly translated as a surname ‘Cheufs’, missing the link to Cranach. Berger. 1901. Quellen für Maltechnik während der Renaissance und deren Folgezeit […] Nebst dem de Mayerne Manuskript: p. 304. The binding medium is linseed oil however, the preparation method of the pigment is the same for watercolors.