Nothing was wasted, and pits and shells of fruits and nuts could be recycled through charring. While collecting those is confined to the harvest season, they can be stored in dried form until processing. Charring was carried out in closed crucibles.[14] After charring, shells and pits keep their initial hardness, hence they require crushing in a mortar before they can be ground on a stone. Grinding on those “stones” is quite labor-intensive.

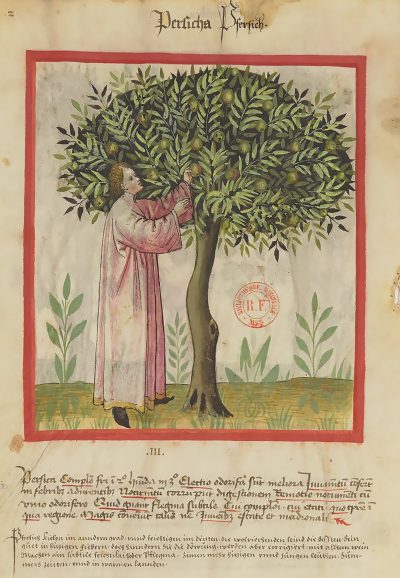

> Charred pits of peach fruits Figures 22a, 22b, 22c Quote 11 / Recipe 9 RECONSTRUCTION

“So nim pfersichstein / thun die in einen nuewen hafen / thun ein fynen behaeben deckel doruff / den verkleib gar wol das kein dampff daruß moege / es würden sonst die stein zu ytel aeschen werden. Den Hafen gib einem hafner der brennen will / das er dir den zu andrem geschirr in ofen setz zu brennen. Wann er dann gebrant hatt / so nimm den hafen unnd thun jn uff, so sind die stein kol schwartz. Die zerstoß in eim mörsel gar klein / unnd ryb sy gar lang unn wol / uff einem stein / biß sy nimme ruch sindt. Temperier sy darnach an mit welcher temperatur du woellest / so hastu gar ein schoen gut schwartz.”[15]

Of all fruit pits, those of the peach (Prunus persica) are certainly the most frequently recorded source for black watercolor pigments. Two fifteenth-century recipes for black pigment, both of Mediterranean origin, refer to peach pits. They make a “perfect and fine black”.[16],[17] They were repeatedly included in many sixteenth and seventeenth-century treatises:

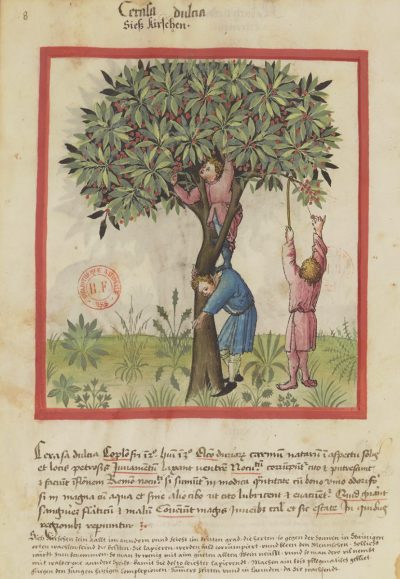

> Charred pits of cherries, apricots and dates Figures 23a, 23b, 23c Quote 12 RECONSTRUCTION

“Noyaulx de Cerises brusles & reduicts en charbon dans vn creuset couuert…”[18]

Mayerne’s discourse with Mr. Huskins, an excellent illuminator, of March 14, 1634 includes the cited recommendation of cherry black. While cherries (genus Prunus) were available, their pits are not mentioned in recipes before 1600. However, later sources list cherry stones frequently as raw material for black pigments,[19] as with pits of apricots (genus Prunus) and dates (genus Phoenix). Peacham in 1634 lists Date stones burnt under “These be the blacks which you most commonly use in painting”, suggesting that sufficient date stones were available in London by then to produce at least smaller amounts of black pigment.[20]

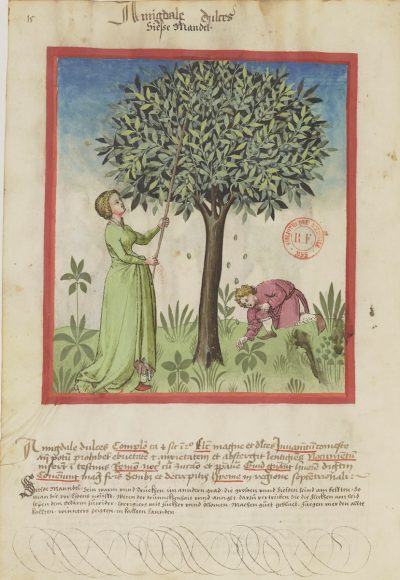

> Charred almond shells Figure 24

Kernels of almonds are surrounded by hard shells. Several Italian authors of the fifteenth and sixteenth century refer to almond shells. These were used for making black pigments, burnt or charred either with the edible kernels, or without.[21] Piemontese in 1561 advises to take either sweet or bitter almond shells, but “if the kernels are inside, it is much better”.[22]

[14] Another method can be found in Piemontese, who advises to let the pits and shells directly burn on a coal fire but stop the process in time, which is rather an incomplete burning. “laetse opte colen verbranden: ende alsse wel root zyn / ende wel gheloeyende / so neemptse vanden viere / ende aldus te colen verbrandt / sult ghyse in een panne bewaren.” Piemontese. 1561. De secreten van den eerweerdighen heere Alexis Piemontois: fol. 111r.

[15] “So take peach kernels / put them in a new pot / and put a fitting lid on them / the lid should be sealed so that no steam comes out / otherwise the kernels would become completely ash. Bring the pot to a potter who is going to a kiln / so that he adds it to the other pottery in the oven. When he finished burning / so take the pot and open it, then the stones are coal black. These pound in a mortar very small / and grind long and well / on a stone / until they are no longer rough. Then temper it with which binder you want / so you have a nice good black.” In: Boltz von Ruffach. 1549. Illuminier Buoch: p. xcvii-xciii.

[16] Cennini. c. 1400. In: Broecke.2015. Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: p. 60-61; Merrifield. 1844. A Treatise on Painting. Written bu Cennino Cennini in 1434: p. 21-22.

[17] le Begue. 1431. citing Eraclius ‘De coloribus et artibus Romanorum’. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 138.

[18] Mayerne. 1620-42. Mayerne Manuscript, London, British Library, MS Sloane 2052: fol. 29r. In: Berger. 1901. Beiträge Zur Entwicklungs-Geschichte Der Maltechnik: p.150,151.

[19] E.g. Hilliard. 1602-03. A treatise concerning the arte of limning: p. 70-73, Norgate. 1621-26. An exact and Compendious Discours concerning the Art of Miniatura or Limning: p. 7, Sanderson. 1658. Graphice, the use of the pen and pensil: p. 57.

[20] Peacham. 1634. The Gentlemans Exercise: p. 71.

[21] Cennini. c. 1400. in: Broecke. 2015. Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: p. 60-61; Merrifield. 1844. A Treatise on Painting. Written bu Cennino Cennini in 1434: p. 21-22.

[22] Piemontese. 1561. De secreten van den eerweerdighen heere Alexis Piemontois: p. 110-111.

[14] Another method can be found in Piemontese, who advises to let the pits and shells directly burn on a coal fire but stop the process in time, which is rather an incomplete burning. "laetse opte colen verbranden: ende alsse wel root zyn / ende wel gheloeyende / so neemptse vanden viere / ende aldus te colen verbrandt / sult ghyse in een panne bewaren." Piemontese. 1561. De secreten van den eerweerdighen heere Alexis Piemontois: fol. 111r.

[15] "So take peach kernels / put them in a new pot / and put a fitting lid on them / the lid should be sealed so that no steam comes out / otherwise the kernels would become completely ash. Bring the pot to a potter who is going to a kiln / so that he adds it to the other pottery in the oven. When he finished burning / so take the pot and open it, then the stones are coal black. These pound in a mortar very small / and grind long and well / on a stone / until they are no longer rough. Then temper it with which binder you want / so you have a nice good black." In: Boltz von Ruffach. 1549. Illuminier Buoch: p. xcvii-xciii.

[16] Cennini. c. 1400. In: Broecke.2015. Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: p. 60-61; Merrifield. 1844. A Treatise on Painting. Written bu Cennino Cennini in 1434: p. 21-22.

[17] le Begue. 1431. citing Eraclius 'De coloribus et artibus Romanorum'. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 138.

[17] le Begue. 1431. citing Eraclius 'De coloribus et artibus Romanorum'. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 138.

[19] E.g. Hilliard. 1602-03. A treatise concerning the arte of limning: p. 70-73, Norgate. 1621-26. An exact and Compendious Discours concerning the Art of Miniatura or Limning: p. 7, Sanderson. 1658. Graphice, the use of the pen and pensil: p. 57.

[19] E.g. Hilliard. 1602-03. A treatise concerning the arte of limning: p. 70-73, Norgate. 1621-26. An exact and Compendious Discours concerning the Art of Miniatura or Limning: p. 7, Sanderson. 1658. Graphice, the use of the pen and pensil: p. 57.

[21] Cennini. c. 1400. in: Broecke. 2015. Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: p. 60-61; Merrifield. 1844. A Treatise on Painting. Written bu Cennino Cennini in 1434: p. 21-22.

[21] Cennini. c. 1400. in: Broecke. 2015. Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: p. 60-61; Merrifield. 1844. A Treatise on Painting. Written bu Cennino Cennini in 1434: p. 21-22.