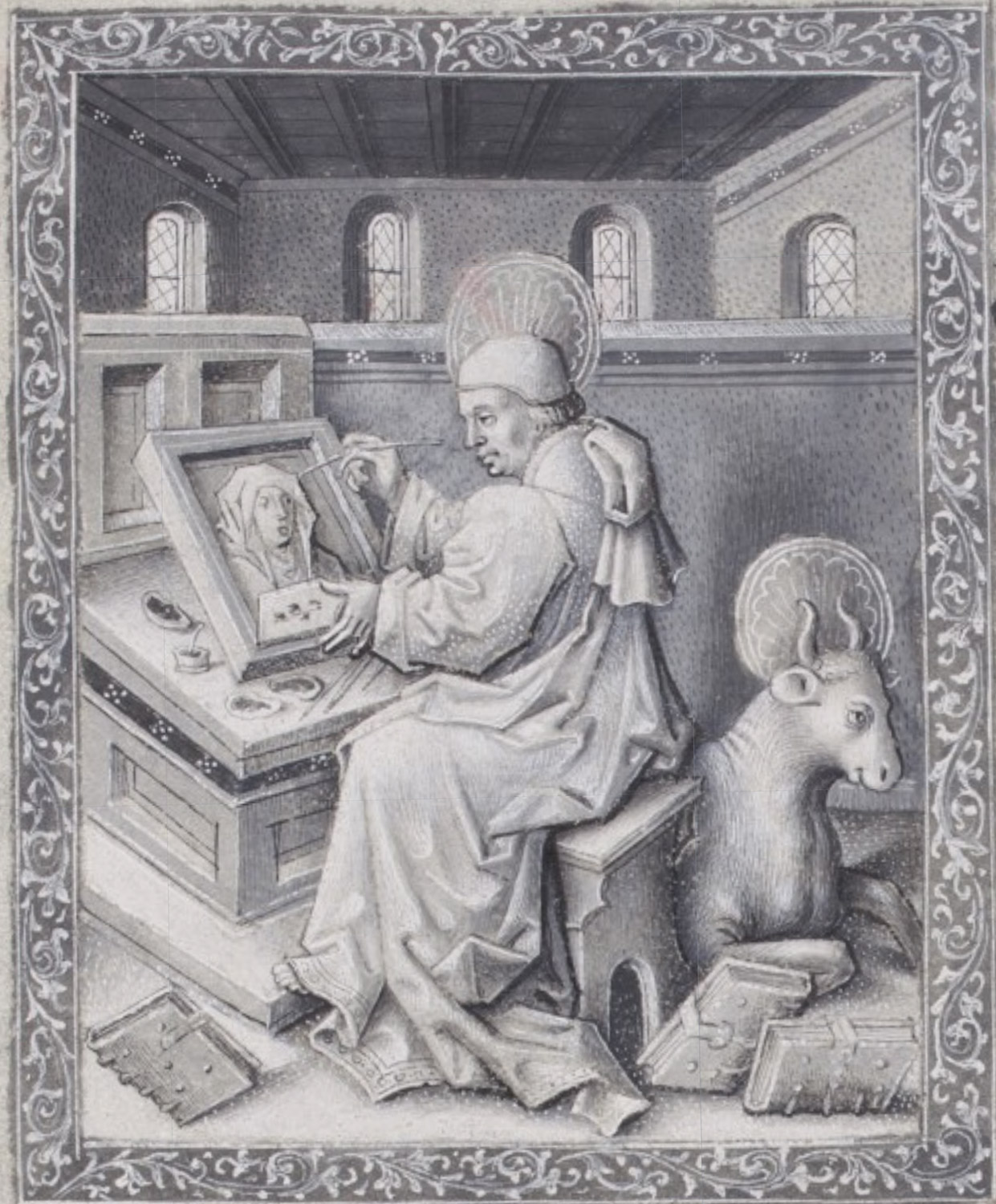

In general, scribes and illuminators constituted two separate professions. While ink was, of course, indispensable for scribes to carry out their writing, copying and calligraphy, it might appear somewhat surprising that it also belonged to the common palette of illuminators. That the differences were less strict is shown in one of the rare miniature paintings that depicts an illuminator in his study (Figure 43). His writing paraphernalia are spread on the table in front of him: goose quills, a knife, a sander and his calamal, a portable container to safely carry writing instruments and the inkwell, which is worn on the belt. It makes sense that his implements for illumination are safely placed on a separate table to is left side below the window.

Diluted ink was widely used for first drafting the contours of a design. In addition, ink was used for shaping outlines or particular features in illuminations, as well as to achieve the finest details in the marginal decorations. Paint mixtures could include inks to achieve specific shades, for instance a grey color. Around 1500, an anonymous author advised to mix the same amount of red paint with good ink to achieve a grey color: “Grijse verue. Nym gueden robrijck ende guet ench darvp gelijck vyl, ende schud sy in eyn horn ende laet yt staen eyn nacht.”[1]

Inks played a prominent role in the specific genre of miniature painting in grisaille that flourished under Burgundian reign. A famous example of the Burgundian era is the Book of Hours of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, created between c.1450-1460. Written by Jean Miélot, secretary of the duke, most of the grisaille illuminations were created by Jean Le Tavernier[2] (Figure 44). Another Burgundian illuminator, also famous for his grisailles, was Jean Dreux, Philip the Good’s valet de chambre, who was active as an illuminator between c. 1430-1467.

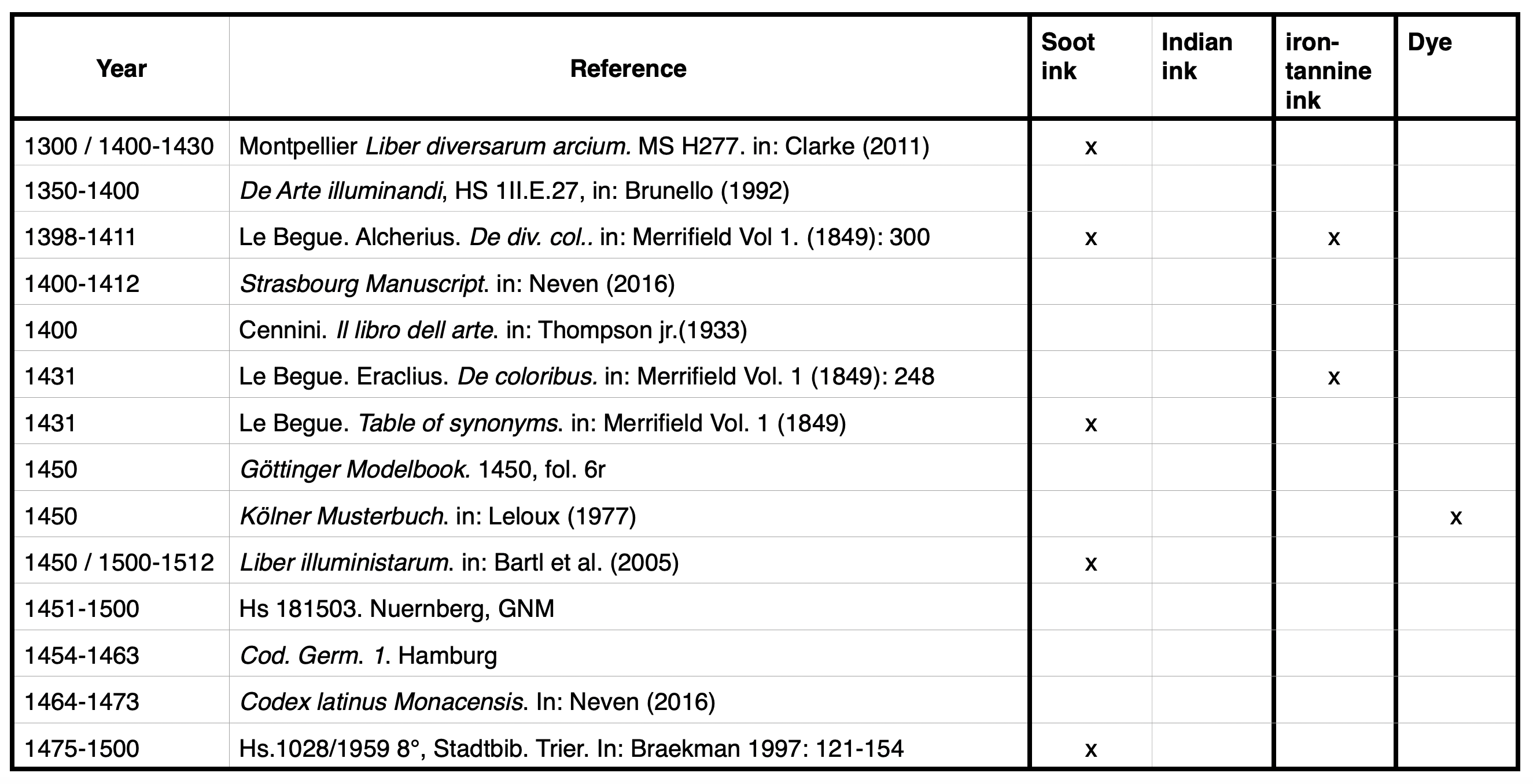

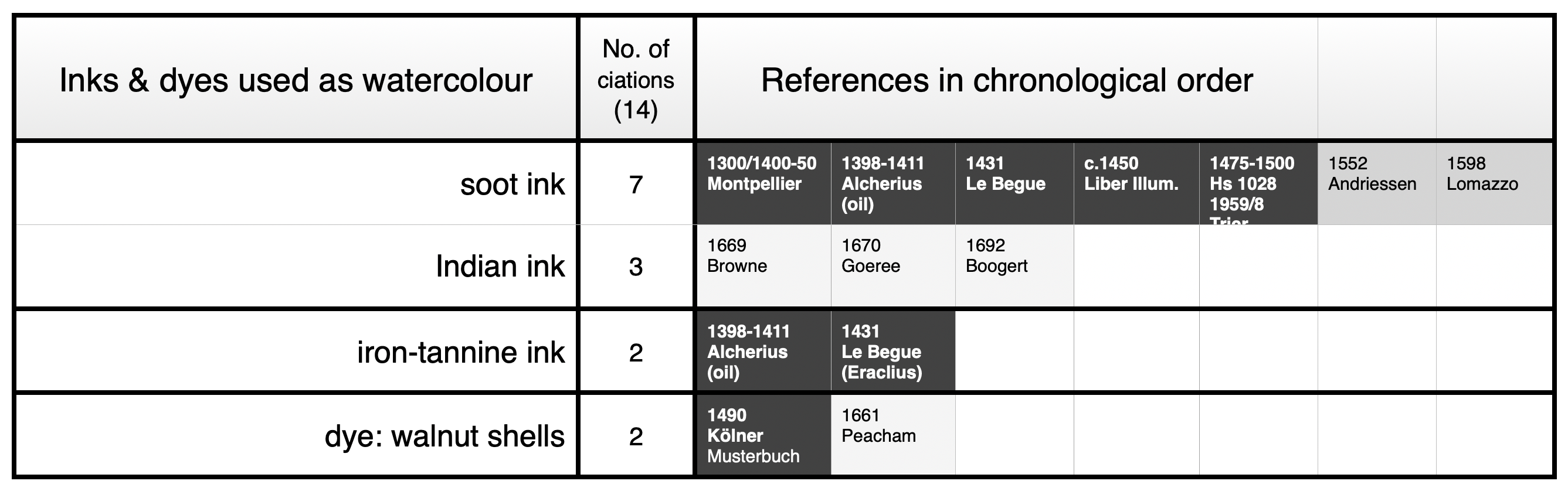

Inks could be used in concentrated or diluted form. Major types of black ink that were used as black pigments were: (1) soot-based inks, (2) Indian inks (3) iron-gall inks, (3) mixtures of both, and (4) dyes.

> Soot inks Figure 45 Quote 23 / Recipe 13, Recipe 14

Inct ter noot te maeken / Dat vierde Capittel. / Ghi sult nemen ene Was caersse ontsteectse / ende holtse tegens een becken oft schottele / tot dat vanden roock roet oft swartsel daer an / hange. Giet dan een weynich warm Gom water / daer in / ende tempereerts doer melcandere soe / ist incte.”[3]

The extremely fine particles of soot make it an ideal pigment for inks. Similar in composition, soot-based watercolors and soot-based inks cannot be differentiated. The application method and the final end product determine the attribution to one or the other – a written document would point to a soot-ink and a painting to a watercolor. Soot-based inks predominated in Islamic and Sephardic writing traditions, as well as in far Eastern cultures. While they were, and for calligraphy still are, widely applied with reed-pens and brushes, their use with quills was less habitual.

Pre-modern European ink recipes, like the quoted one by Andriessen, usually refer to soot-based inks as inks ‘to prepare in exigency’, usually if iron-gall ink was not available. It could be easily produced anywhere, which is useful while travelling. If ink was required, the smoke of a candle was collected onto a dish and mixed with dissolved gum Arabic or other binding media like egg white. The composition of the candle could vary from a cheap tallow candle, a wax candle as in the above cited recipe, but also a self-made candle from pitch/tar, as an anonymous author of the mid fifteenth century recommends: “Jte wiltu ein schwartz tinten / machen So nym vnn mach kertz/lin mit bech vnn zȗnd sye an / vnd vach den roch in ein bekin / als vil du machen wilt Vnd / nym denn den roch vnn temp/irn mit gumywasser vnn lasß / es denn dorren Vnd mach sy / denn aber mit gumy wasser / sy wirt gūt vnn schat den / ougen nit.”[4] For illuminators, soot-based inks would have been easy to apply either with a quill or with their super-fine brushes, diminishing any proper distinction between watercolor and ink.

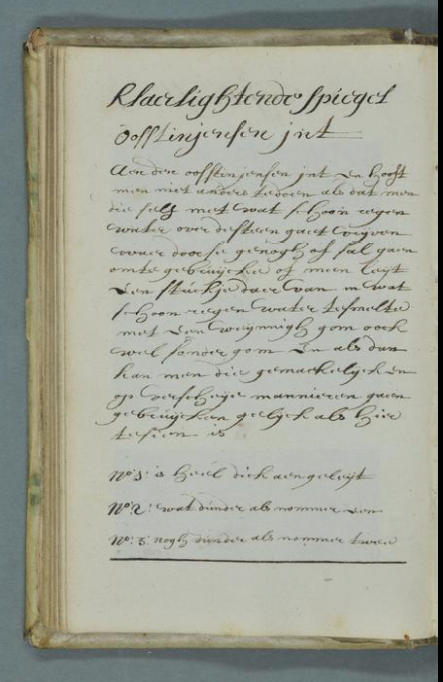

> Indian ink Figure 46 Quote 24 / Color sample 9

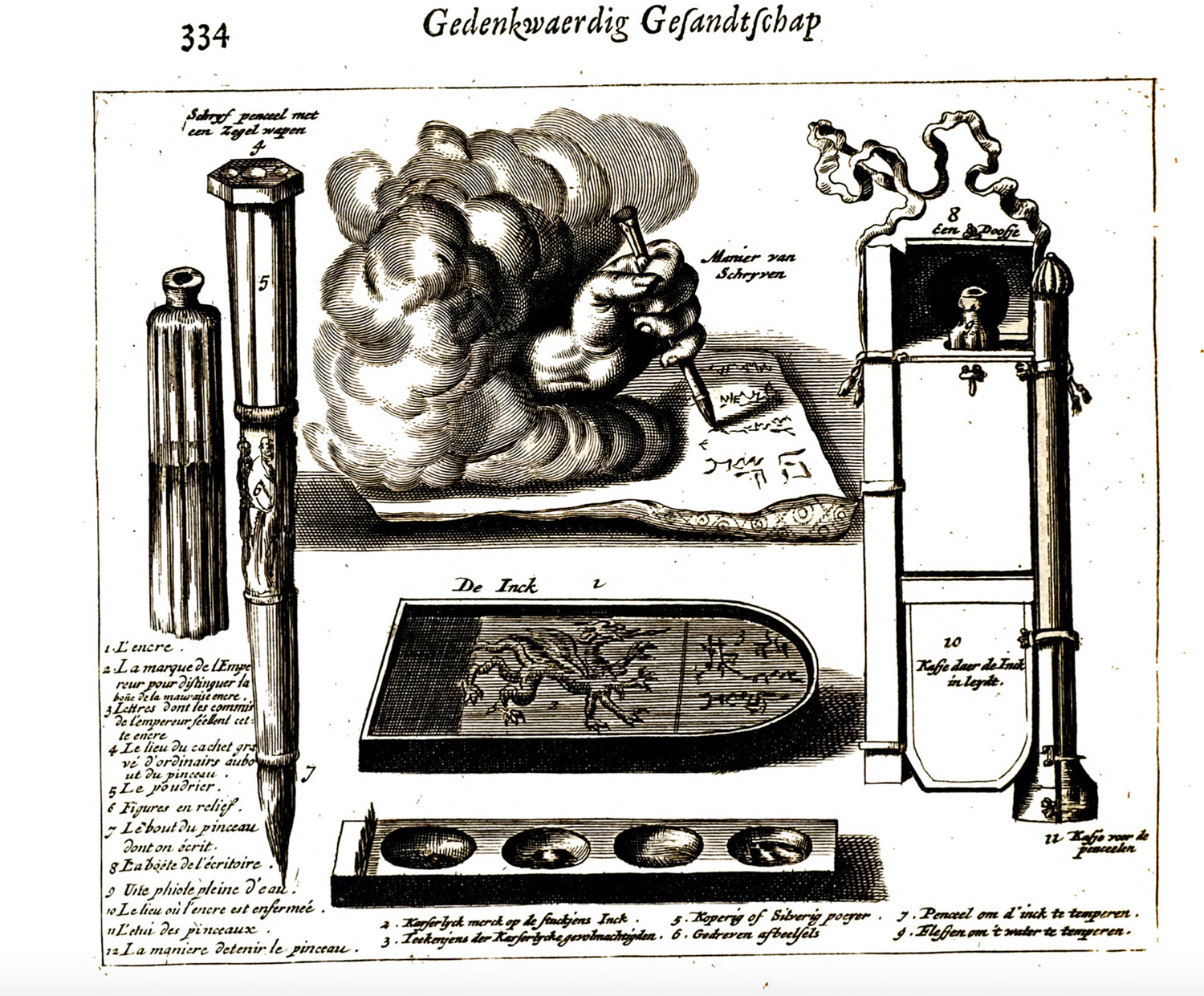

“Oosstinjenhen ink. Aan den oosstinjenhen ink en hooft / men niet anders te doen als dat men / die self met wat schoon regen / water over de steen gaet vrijven / waer door se genogh of sal gaen / omte gebruijcken of men leijt / den stuckje daar van in wat / schoon regen water tesmelte / met den weijnigh gom oock / wel sonder gom en als dun / kan men die gemackelijck en / op verscheije mannieren gaan / gebruijcken gelijkck als hier tesien is.”[5]

Indian ink became fashionable as soon as trade brought this product to Europe (Fig 46). Many seventeenth-century limning manuals refer to Indian ink. The ink was sold in the form of hard sticks which required rubbing on a stone with water to release the intensely black ink. The use of brushes for Far Eastern calligraphy might have inspired the use of Indian ink as a watercolor in Europe.

Color sample 9

For centuries it remained a secret how Chinese and Japanese ink makers could succeed in producing ink sticks that show such brilliant and deep black shades. Many attempts to render this black were made, usually in vain. Sources warn against fake Indian ink and include advice on how to test its quality, as in the complaint of Valentini in 1704: “Die Holländer sollen sie heut zu Tag nachmachen / aber bei weitem nicht so schön und gut; der Unterscheid ist daran zu erkennen / daß die Holländische graulicht=schwarz aussiehet und aus blatten Stückern bestehet / da hergegen die rechte Sinesische schön gläntzend schwarz und in Fingers-dicken Stücken kommet.”[6]

One difference lies in the binding medium – far Eastern inks are made with proteinaceous glues, European inks and watercolours with gum Arabic.[7] Of equal importance is the production of black pigment for ink making, which was refined through the centuries. Far Eastern ink makers were and are aware of the finest nuances in tonality that can be obtained by choosing blacks made either from particular vegetable oils or from the soot of specific conifer tree species. Selling Indian ink in the form of sticks was a clever method to prevent leaking, drying out and molding, ideal for keeping it in tropical climates and for surviving months of transport in ships.[8] Indian ink sticks were the precursor of the first European commercially traded watercolors, which were sold in the form of hard cakes, invented by Reeves in 1766.

> Iron-gall inks Figure 47 Quote 25 Recipe 15, Recipe 16

303a. Autre Recepte pour /aire encre. […] Prenes ung quarteron de noiz de galle de iiij deniers parisis et faites batre en pouldre, puis la metez en quatre et demie diaue et la faites boulir une heure et demie ou plus a beau feu de charbon et jusques atant que leaue soit revenue a la quarte ; et puis quant elle aura ainsi bouli, y mette&un quarteron de gomme de iiij deniers et plain gobelet de vin aigre ; et puis le faites boulir une autre heure et puis quant elle aura boulu, la descendez et y metez un quarteron coperose en pouldre de iij deniers parisis, et le laissiez refroidier puis metez en un cellier. Et se elle est trop clere blanche si y metez encore un pou de coperose et vous aurez bon encre.” [9]

The most frequently used ink in scriptoria and later by secular scribes was iron-gall ink. It is easily made by preparing a decoction of crushed oak galls (or substitutes like bark of alder trees[10] or other tannin-containing plant parts) together with iron sulphate (green vitriol, copperas) in a liquid like wine, beer or water. Gum Arabic is added as a dispersing agent. As a result of the chemical reaction between iron ions and tannin a dark blue-blackish liquid, an iron-gall ink, is formed. This reaction was widely known at least since late antiquity and applied not only for ink making, but also for dyeing textiles or leather black.[11] Over time iron-gall inks change their color to brown, often distorting the original impression, especially in grisaille drawings. They flow easily from the quill and are difficult to remove, hence their success as writing and drawing ink. Many publications focus on iron gall ink therefore, they are not discussed here in depth. [12]

> Mixture of carbon-based inks and iron-gall inks

To render an ink intense black but to keep its permanence, mixtures of carbon-based and iron-gall inks were used.

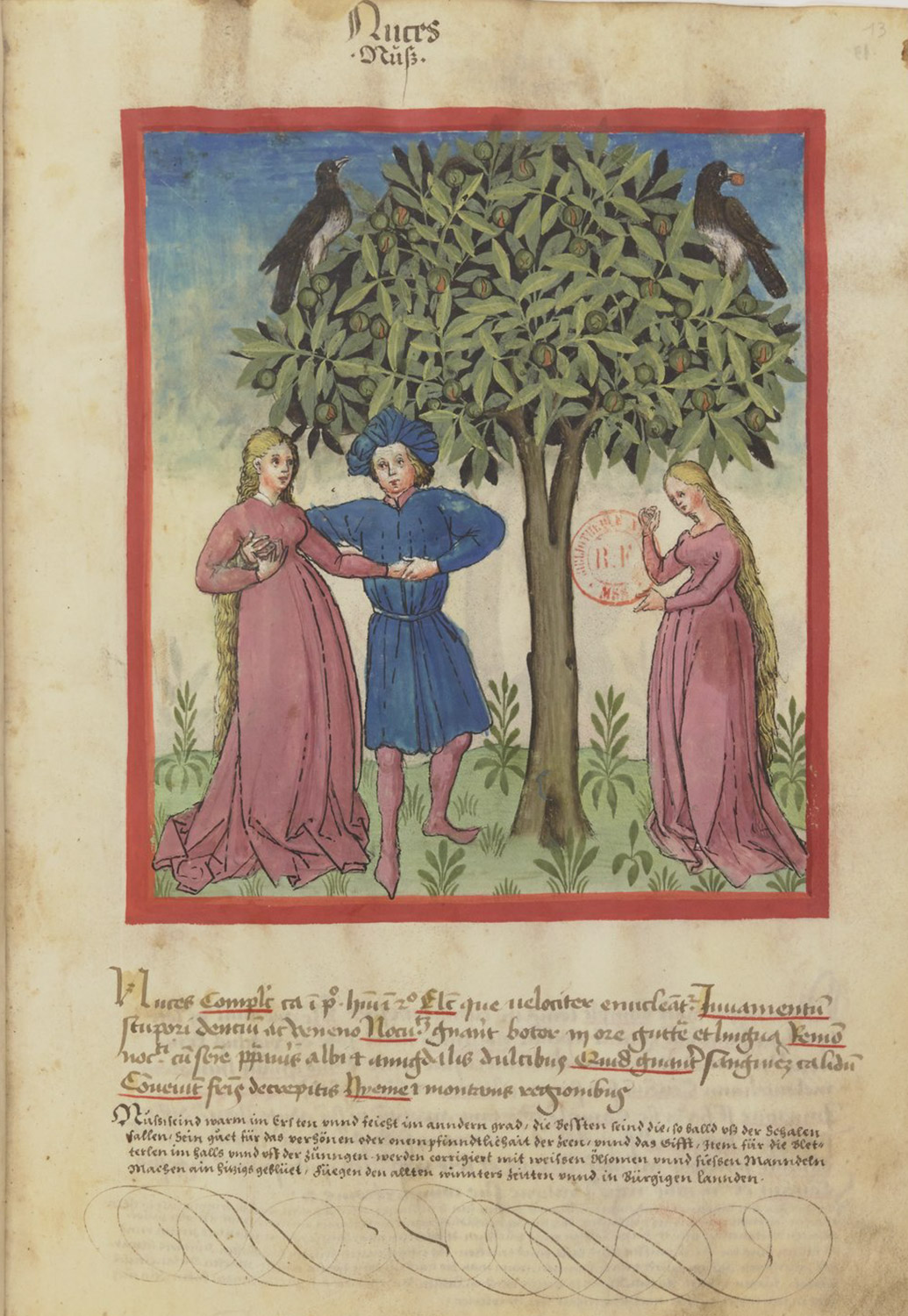

> Dyes Figure 48a, 48b Quote 26 Recipe 17

“Item novvs modvs faciendi incaustum substancie. / Nemet bulsteren van walnoeten enn laetse / droghen ij off drie daghe enn laetse stoten / in een mortiersteen enn do dat in een ketel enn / laetet smelten. Dan sla dat doer een lynnen / doeck. enn doet in een pot off blase. dit is die substancie. Hijr van nym een menghe / myt wyn off etick enn water enn latet warm / werden hent dattet smelte dat wort guet.”[13]

Using dyes to make a black ink is seldomly recorded. Some authors mention the use of walnut shells, particularly in connection with substantien inkt, for instance in the quoted recipe of c. 1490. This is logical considering the abundance of black pigments that were easily available to illuminators and the lack of natural dyes that are able to reach a deep intense black.

[1] “Grey color. Take a lot of good rubric and good ink, put them in a horn and let it stand for a night.” Hs.1028/1959 8°. end of fifteenth century – beginning sixteenth century. Stadtbibliothek Trier: fol. 28r. In: Braekman. 1997. Warenkennis, Kleurbereidingen Voor Miniaturisten En Vakkennis Voor Ambachtslui (15de E.): p. 140, rec. 50.

[2] Royal Library the Hague, https://www.kb.nl/themas/middeleeuwen/getijdenboek-philips-van-bourgondie

[3] “To make ink in need. Chapter four. Take a wax candle, light it and hold it against a bowl or a dish until soot or the black from the soot sticks to it. Then pour a little warm gum water into it and temper it so it’s ink.” In: Andriessen. 1552. Viervoudich Tractaet Boeck: fol. 40. https://books.google.nl/books?id=wZNiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=de#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[4] “Item If you want to make a black ink, take and make a candle with pitch. Light it and catch as much smoke as you want in a basin. Then take the soot and mix it with gum water and let it dry. Use gum water to prepare the ink. It is good and does not harm the eyes.” Codex Germanicus 1. 1454-1463. Hamburg, Staats-und Universitätsbibliothek, Cod. Germ. 1: fol. 71r https://mittelalter.hypotheses.org/files/2017/12/073r.jpg

[5] “With regard to Indian ink one does not need to do anything else, than to grind it with some clean rainwater on a stone, so that enough will come off to be used; or put a piece of it in some clean rainwater to melt with a little gum, also without gum; and then one can use it easily and in different ways as can be seen here.” Boogert. 1692. Klaer lightende Spiegel der Verfkonst, Bibliothèque Méjanes in Aix-en-Provence, MS 1389 (1228): Without page number.

[6] “The Dutch imitate it today, but nowhere near as beautifully and well. The difference can be recognized in so far that that the Dutch looks grayish = black and consists of flat pieces, whereas the real Chinese comes in beautiful shiny black and in finger-thick pieces.” In: Valentini. 1704. Museum museorum: p. 23 https://archive.org/details/museummuseorumo00vale/page/n0.

[7] Reissland and Hoesel. 2019. Manuscripts from Yemen – Analysis of Glittering Particles and Ink Composition. RCE Research report 2016–027a.

[8] Also, other ink cultures searched for ways to preserve their ink. Middle Eastern ink was dried as cakes. The European alternative was to carry inks as powder that could be mixed with any liquid available, like beer, wine or water to create a writing ink.

[9] “Take a quarter of a pound of gall-nuts of the weight of iiij. Parisian deniers, and let them be beaten to powder. Put it [the powder] into a quart and a half of water, and let it boil for an hour and a half or more on a good charcoal fire until the water is reduced to a quart ; and when it has thus boiled put into it a quarter of a pound of gum of the weight of iiij. Parisian deniers and a cup full of vinegar; and then make it boil another hour, and when it has boiled, take it off and put into it a quarter of a pound of copperas in powder of the weight of iij. Parisian deniers, and let it cool, and then put it into an inkstand. And if it is too pale add to it a little more copperas, and you will have good ink.” In: Le Begue, 1431, BnF, MS Latin 6741, fol. 92r https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10525796f/f188.item

[10] Archerius mentions the use of alder bark: “Or take the bark of alder and grind it with iron filings in water” In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 300.

[11] See essays on dyeing in part III of this volume.

[12] Reissland and Ligterink, The iron gall ink website. https://irongallink.org

[13] “Item A new mode to make substantie ink. Take walnut husks and let them dry for 2 or three days and pound them in a stone mortar and put that in a cauldron and let it melt. Then strain it through a linen cloth and put it into a pot or a bladder. That is the substantie. Take an amount of this with wine or vinegar and water and let it get warm so that it dissolves. This is going to be good.” In: Kölner Musterbuch. 1490. Köln, Historisches Archiv der Stadt, Best. 7010 (Wallraf) 293: fol. 4v

[1] “Grey color. Take a lot of good rubric and good ink, put them in a horn and let it stand for a night.” Hs.1028/1959 8°. end of fifteenth century - beginning sixteenth century. Stadtbibliothek Trier: fol. 28r. In: Braekman. 1997. Warenkennis, Kleurbereidingen Voor Miniaturisten En Vakkennis Voor Ambachtslui (15de E.): p. 140, rec. 50.

[1] “Grey color. Take a lot of good rubric and good ink, put them in a horn and let it stand for a night.” Hs.1028/1959 8°. end of fifteenth century - beginning sixteenth century. Stadtbibliothek Trier: fol. 28r. In: Braekman. 1997. Warenkennis, Kleurbereidingen Voor Miniaturisten En Vakkennis Voor Ambachtslui (15de E.): p. 140, rec. 50.

[3] “To make ink in need. Chapter four. Take a wax candle, light it and hold it against a bowl or a dish until soot or the black from the soot sticks to it. Then pour a little warm gum water into it and temper it so it's ink.” In: Andriessen. 1552. Viervoudich Tractaet Boeck: fol. 40. https://books.google.nl/books?id=wZNiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=de#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[3] “To make ink in need. Chapter four. Take a wax candle, light it and hold it against a bowl or a dish until soot or the black from the soot sticks to it. Then pour a little warm gum water into it and temper it so it's ink.” In: Andriessen. 1552. Viervoudich Tractaet Boeck: fol. 40. https://books.google.nl/books?id=wZNiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=de#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[5] “With regard to Indian ink one does not need to do anything else, than to grind it with some clean rainwater on a stone, so that enough will come off to be used; or put a piece of it in some clean rainwater to melt with a little gum, also without gum; and then one can use it easily and in different ways as can be seen here.” Boogert. 1692. Klaer lightende Spiegel der Verfkonst, Bibliothèque Méjanes in Aix-en-Provence, MS 1389 (1228): Without page number.

[5] “With regard to Indian ink one does not need to do anything else, than to grind it with some clean rainwater on a stone, so that enough will come off to be used; or put a piece of it in some clean rainwater to melt with a little gum, also without gum; and then one can use it easily and in different ways as can be seen here.” Boogert. 1692. Klaer lightende Spiegel der Verfkonst, Bibliothèque Méjanes in Aix-en-Provence, MS 1389 (1228): Without page number.

[7] Reissland and Hoesel. 2019. Manuscripts from Yemen - Analysis of Glittering Particles and Ink Composition. RCE Research report 2016–027a.

[8] Also, other ink cultures searched for ways to preserve their ink. Middle Eastern ink was dried as cakes. The European alternative was to carry inks as powder that could be mixed with any liquid available, like beer, wine or water to create a writing ink.

[8] Also, other ink cultures searched for ways to preserve their ink. Middle Eastern ink was dried as cakes. The European alternative was to carry inks as powder that could be mixed with any liquid available, like beer, wine or water to create a writing ink.

[8] Also, other ink cultures searched for ways to preserve their ink. Middle Eastern ink was dried as cakes. The European alternative was to carry inks as powder that could be mixed with any liquid available, like beer, wine or water to create a writing ink.

[11] See essays on dyeing in part III of this volume.

[11] See essays on dyeing in part III of this volume.

[11] See essays on dyeing in part III of this volume.