The third Duke of Burgundy of the Valois family, Philip the Good is famous for having only worn the colour black upon the death of his father, John the Fearless, in 1419, as a sign of mourning.[1] When he was not in the red coat of the Golden Fleece,[2] he had been seen since the fifteenth century as the man in black wearing a chaperon with padded roll, with the Golden Fleece necklace, as represented in his official portrait [Figure 1]. In art historical scholarship, beginning perhaps with Johan Huizinga’s Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen (The Autumn of the Middle Ages),[3] (1919) with its vivid descriptions of the duke’s taste for funeral pomp, a stereotypical picture of the Third Duke of Burgundy took hold in which black was predominantly associated with starkness, darkness, and death, under the influence of a rather negative and Romantic view of that colour. Since then, further research has been carried out on ducal clothing,[4] on the practice of mourning,[5] and on the colour black.[6] Against the background of this historiography, this article looks again at the question of Philip the Good’s use of black, to review how the duke built a lasting image by choosing to wear only black clothes.

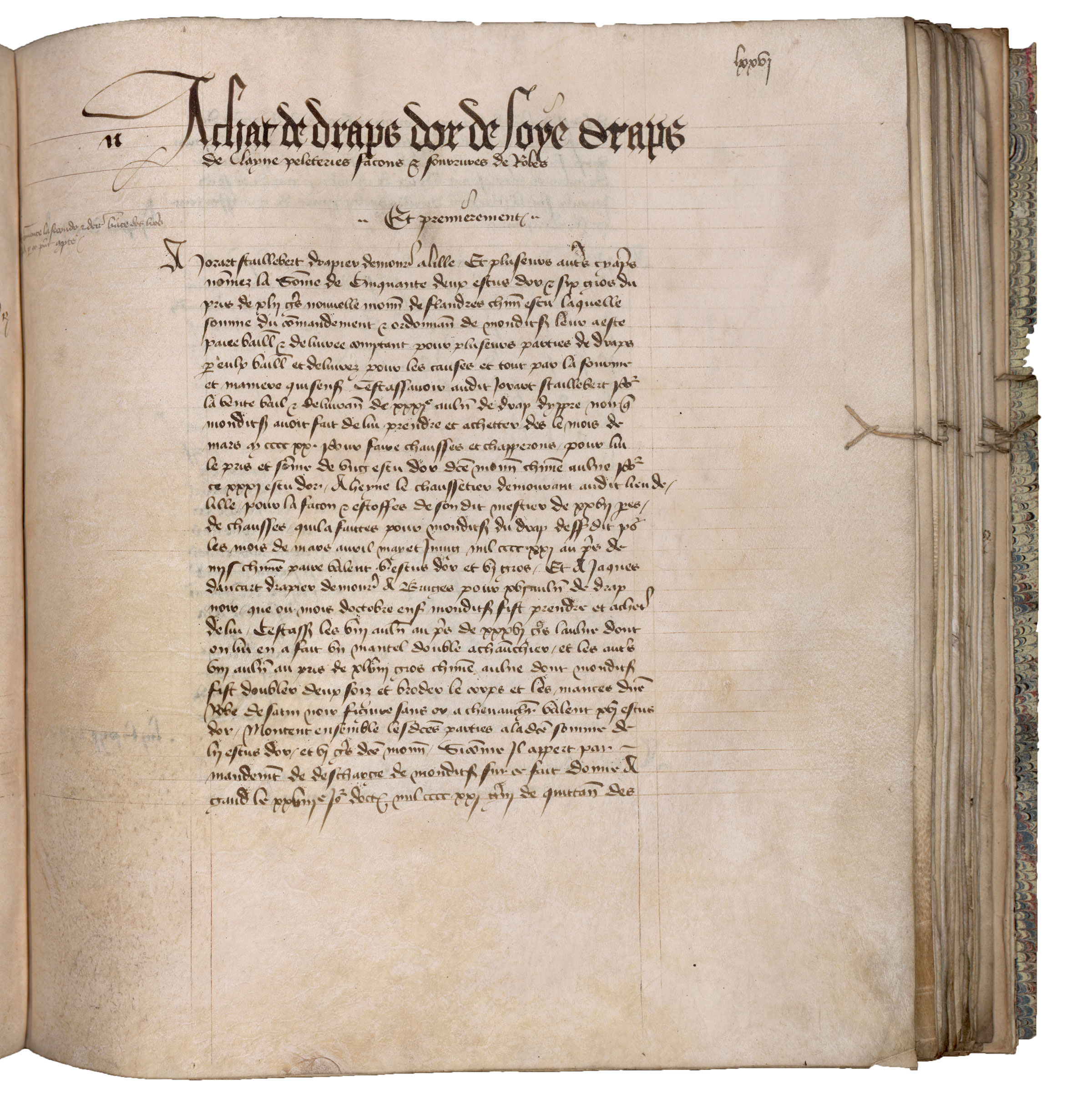

The Burgundian court is distinct from other European courts in that it is particularly well documented. First, in pictures: a good part of the library of the dukes of Burgundy has been preserved, and the dukes were patrons who supported painters. Miniatures, portraits, or other paintings made in their surroundings are kept in these libraries. The images represent in particular scenes of life at the court of Burgundy, and the characters are often represented in clothes whose shapes closely resemble those worn by contemporary readers. In terms of texts, Burgundian court culture was also rich in fictional prose, stories, treatises, and poems; particularly useful to modern historians, the dukes maintained chroniclers, or semi-official historians responsible for recounting the political events of the reign. These chroniclers speak of clothing when it seems to them remarkable, particularly if it’s rich or worn in unprecedented circumstances.[7] Finally, the ducal administration produced reams of documents in its daily operations, many of which have been preserved: lists of officers (hotel ordinances), inventories of property, jail records (lists of officers on duty, day-by-day), revenue and debit accounts, expenses, etc. The Burgundian accounts form one of the best preserved of all court accounts: the registers of the ‘general revenue of all finances’ (i.e. ‘Les comptes de la recette générale de toutes les finances‘) are almost complete over the entirety of the long reign of Philip the Good (1419-1467), with only four years out of 48 missing from the Departmental Archives of the North in Lille. Written in French with clarity and rigor by a Receiver General, they regularly mention the purchases of cloth and accessories, and also mention the costs associated with fur clothes and jewelry for the duke or part of his entourage [Figure 2].[8] (The data from this accounting were systematically analyzed for the period 1430-1455, and I present those findings below.)[9] Combined, these documents provide a privileged overview of the traces of material life at the court of Burgundy, and this overview helps to shape a new hypothesis about the way Philip the Good dressed, explaining why Philip the Good only wore black clothes by analyzing these records of his wardrobe in relation to his ideas about mourning, his religious feeling, and his political strategies.

Black for Mourning?

The still-popular association of black clothes with mourning combines a sense of religious austerity with potential intimations of vengeance. When it was established as the norm in Philip the Good’s court, however, it was established in a context marked by a strong national feeling, when it was difficult to accept that his father, the Duke of Burgundy, had ‘delivered France to England.’ This national feeling grew strong when Philip the Good learned of his father’s death and chose to oppose the party of the Dauphin by joining forces with the English. This reversal was a revenge strategy, which seems to have been rather painful for the Burgundians.[10] In the wake of this controversy, Philip the Good appears to have chosen to mourn his father, John the Fearless (1371-1419), in his public appearances, to show that, by signing the Treaty of Troyes a year later in 1420, he was not committing sacrilege, but was instead making a sacrifice for the good of the realm. This story, as recounted in Huizinga’s florid prose, is the standard account: ‘And if the honour of a proud family was at stake and revenge was imposed as a sacred duty, as it was the case during the murder of John the Fearless, the appearance corresponded to the colour of the heart.’[11] However, by allying himself with the English, the duke sought above all to punish the guilty parties for a crime considered as a lèse-majesté and, undoubtedly, to prevent the Dauphin Charles from getting too close to the English.

Historiography has long been satisfied with this explanation. One author went even further, assuming this habit of wearing black was the prince’s wish, not only for himself, but also for his entourage.[12] Do the ducal accounts support the longstanding hypothesis that Philip the Good radically modified his wardrobe in 1419 as a sign of mourning? And did he — after the death of his father — impose the colour black, for the same reason, on his entourage?

Black at the Burgundian Court before 1419

At the very least, we can say that black was certainly already a fashionable colour before the assassination of John the Fearless in 1419, associated with celebration, and not necessarily with mourning, as Michel Pastoureau has shown. According to Pastoureau, black as a precious, deep, rich colour appeared in court, first in Italy. The colour then reached French courts through Valentine Visconti, wife of the Duke of Orleans (1371-1408).[13]

The childhood clothes of the Count of Charolais (a title held by Philip the Good before he entered the Duchy of Burgundy) were not all financed by the Duke of Burgundy’s hôtel, or the personal organization of his house, meaning that we have only partial information on the clothes he wore during his childhood. More complete data is available, however, about the outfits of the first Valois Dukes of Burgundy, Philip the Bold (1342, duke in 1364 – 1404) and John the Fearless (1371, duke in 1404 – 1419). Their preferences were generally for green and red, but black nonetheless featured in their outfits. Records show, for instance, that in 1396, Philip the Bold took charge of the production of clothes for great Burgundian and French figures to welcome English ambassadors, and he chose black silk, velvet and satin to make these clothes.[14] However, at that time and until his death, the first Duke of Burgundy Philip the Bold preferred red (vermeil and crimson) and green, for himself and for his liveries.[15] John the Fearless, firstly as Count of Nevers[16] and then Second Duke of Burgundy,[17] also purchased black cloth. At the turn of the century, black was already present in the silk garments of the Count of Nevers: velvet, satin, black and vermeil ash (‘cendal’). On the other hand, a more important chromatic variety was found among woolen materials: grey, brown, scarlet, white, and especially green (gray-green and brown-green). Thus, black was undeniably present at the Burgundian court before Philip the Good became duke, but evidently not favored above other colours. The few purchases identified in the accounts intended for the Count of Charolais, future Duke Philip the Good, are consistent with this pattern, although the data concerning him remain partial, corresponding to moments when he was present alongside his father. This situation persisted until 1419, and a systematic study of the accounting confirms this impression. But the question remains, did the death of John the Fearless mark a chromatic change in the attire of the young duke?

Any account of a change in fashion after the death of John the Fearless must recognize a shift in the wider court culture, which was more obviously oriented toward the spectacular. The first account of Gui Guilbaut, Receiver General for all Finances, covering the period from 3 October 1419 to 3 October 1420, records part of the first clothing expenses incurred by the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good:

Fifty aunes of woolen black cloth to make eight robes and eight chaperons for the pages, groom and footman of the here-mentioned lord, for the duel of the late master, the duke’s father, may God have mercy.

32 aunes of white cloth to line the aforementioned robes

28 aunes of another black cloth of which one makes for the said lord the robe, long mourning coat and chaperon

For Pierre Gravelot and several others hereafter named the sum of nine hundred thirty six pounds and twelve sous two deniers royal coins that should be enough for them to purchase cloth for making robes, coats and chaperons for the here mentioned Lord and the members of his hotel and the hotel of the lady Duchess of Burgundy his wife, that are all together 146 persons

240 aunes of brunette cloth … and for 376 and a half aunes of another cloth for making the lining for the aforementioned robes.

183 aunes and 3 quarters of brown cloth

200 and 1 aunes of cloth to make the linings

(…) 117 aunes of brown cloth for making 26 robes and 26 chaperons, for each robe and chaperone 4 and half aunes of cloth [18]

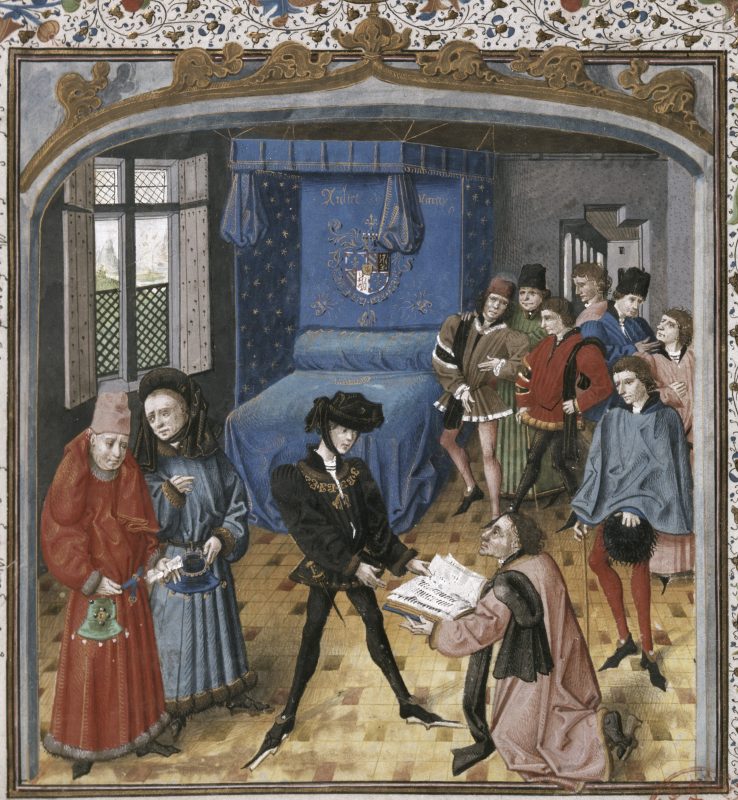

The elaborate expense here shows, as Bernard Guénée emphasizes, how the luxury and the power of the prince became, at the end of the Middle Ages, ‘a stake of legitimacy in the eyes of his subjects.’ This luxury marks, according to this Guénée, the origin of l’hôtel ducal, that is, the creation of his personal household as an enormous and very populous ducal apparatus, responsible for providing for the duke’s necessities and glorifying his majesty. Soon the idea arose that in the entourage of the prince there was to be a spectacle, a staging for the sake of a perfectly regulated hierarchy: ‘a courtyard has thus become a sumptuous scene’ Guénée argues, ‘where the prince and his entourage now play a role fixed in its smallest details by the ceremonial.’[19] In this way, Philip the Good both increased the significance of court spectacle and magnified the memory of his father by purchasing a large quantity of black clothes made for the officers of the hôtel. This duke seemed, then, from the beginning of his reign, attached to ceremony and protocol based on tradition and ancient customs, which would later become court etiquette. In European courts more broadly, this period also saw a comparable move to draft novel, elitist customs in many areas, including sumptuary laws,[20] hôtel ordinances,[21] and ceremonial accounts,[22] primarily in response to the ‘turmoil’ of a changing society.

This large quantity of black clothing made for the hôtel‘s officers, and recorded in the accounts, seems to support the hypothesis that Philip’s monochromatic appearance should be interpreted as a sign of prolonged and rigorous mourning, mediated by the imperatives of spectacle. On the death of John the Fearless, the Burgundian court engaged in practices of mourning and funeral ceremonies in a set of essentially noble rituals that they gradually developed and codified.[23] Significantly, as previous accounts of Philip the Good’s black wardrobe suggest, the court used the colour black in these rituals to show both pitiable mourning and the social rank of the deceased, through an ostentatious and solemn procession in which black was omnipresent: everyone wore black clothes, even the horses, a black sheet covered the coffin, other black drapes were stretched out in the streets and in the church.[24] Indeed, in using black as the colour of mourning, the Burgundian court was adopting the fashion rather late[25] and was importing it from Spain.[26] Historians have argued that this turn towards black associated the colour with the evolution of religious sentiment, the birth of purgatory, the conception of death associated with night, and with darkness. The mourning ceremony is based on a desire to treat the dead well and to preserve their place in the society of the living, meaning that performance was, in several senses, for the dead.

However, it is important to note that these mourning clothes, clearly identified as such in the account statements, shared a significant characteristic: they were all made of black wool. The outfits consisted at least of a black dress and a chaperon and, for Philip the Good, a coat of black wool, which was probably amply cut [Figure 3]. It is also important to distinguish between clothes used for the funeral procession and those more specifically tailored for mourning. The dress worn under the coat could display the latest fashion trends. It seems that the duke himself was compelled, in memory of members of his family, and for a period of time that remains difficult to measure, to mourn.

John of Luxembourg and Jack of Harecourt, two officers of John the Fearless, allied to the Burgundy family, stood beside him in black as part of the ceremony associated with the death of a state figure. Most likely, the duke was adopting an attitude in step with that which was expected of him, and his clothing consequently does not seem to have caught the attention of contemporary commentators and chroniclers: in the Enguerrand de Monstrelet chronicle,[27] for instance, there is no mention of an official decision by the new duke to restrict himself or his entourage to an outward appearance of permanent mourning. Even the chronicler Georges Chastellain (c. 1405 or 1415 – c. 1475), who describes vividly the pain of Philip the Good’s bereavement, does not attribute such intentions to him.[28] Therefore, the proposal for a radical and definitive adoption of the colour black as a sign of mourning by Philip the Good on 10 September 1419 remains debatable.

Dressing Up as a Prince

Though it’s clear that we see the use of black clothing around the mourning for Philip the Fearless, we should not confuse the black of mourning with the fashion of black that was already well established in the court of Burgundy before the death of John the Fearless, which resulted in a preference for dark silks, often woven of gold, and for dark, natural or dyed furs and skins.[29] To understand the character of Philip the Good’s fashion choices, we must consider this broader shift in fashion toward blackness, and we need to recognize that his fashion choices were not wholly driven by mourning considerations. The clothes made for Philip the Good between 20 March 1420 and All Saints’ Day 1422, for instance, were mostly black, but there were also clothes of other colours, including a short blue silver dress with open sleeves, made in Lille, two pairs of scarlet hose embroidered with the ducal motto (‘Autre n’aurai‘), a scarlet dress of two fabrics cut with leaves for the wedding of the Lord of Uutkerke’s daughter, a scarlet velvet houppelande embroidered with gold.[30] The new Duke of Burgundy adapted his wardrobe to his new role of prince. However, the presence of coloured clothing in his wardrobe after his father’s death calls into doubt the idea that he was in perpetual mourning, which makes the case for Philip the Good’s drawn-out performance of grief seem unlikely. Indeed, if Philip the Good wore black as a matter of mourning, we would be surprised that mourning was not broken after reconciliation with the party of Charles VII, following the Treaty of Arras (1435). On the contrary, however, Philip the Good adopted the colour black precisely in the years that followed. It is therefore necessary to find other explanations for the systematization of black in ducal clothes.

Philip the Good’s Choice of Black

During the 1430s, Philip the Good still occasionally wore grey clothes alongside a predominantly black wardrobe. On the other hand, from the end of the 1430s, black was definitely and very visibly present in his entire wardrobe. The majority of ducal garments were black (932 pieces between 1430 and 1455), or grey (50 pieces), or even both combined (23 pieces) at the beginning of the period. Other colours appeared only very sporadically: a green hood, four white garments, a blue robe, three purple. Finally, a few garments, all made for the Golden Fleece, were scarlet or a ruddy scarlet. If we bring these data back to the chronology, it appears that the variety was more present at the beginning of the period: of the 90 coloured pieces, 81 were worn before 1436.[31] After 1436, the only colour he allowed himself to wear outside black was the red cloak of his order of knighthood of the Golden Fleece.[32]

Therefore, if the mourning thesis does not hold up, could his decision have been governed by a feeling of humility or penance? Making the connection between religious sentiment and clothing was attempted by Agnes Page, who noted this link in the costume of Duke Louis of Savoy between 1444 and 1447.[33] In analyzing the ducal garments, she hypothesized that the Duke of Savoy, often adorning himself with white, both inside and outside in some of his garments, was seeking to express a Christian ideal of humility (albus white) and eternity (candidus white). The comparison between the Savoy statutes and the accounting data suggested that the frequent use of lower quality woolen materials including lamb’s wool, sold at low prices, indicate that the duke wanted to show a certain sobriety in his clothing. Page here suggests the mystical qualities of the lamb, and vision of the duke as a figure of religious purity (the idea of God’s flock, guided and not sovereign). Can we make the same analogy about the Duke of Burgundy to decrypt a certain religious sentiment in his outfits?

If we compare the wardrobe of Philip the Good with that of the Duke of Savoy, the juxtaposition is striking. The Duke of Savoy had fifty outfits of varying quality made for him between 1444 and 1447. For Philip the Good, there were 162 outfits.[34] (Temperantiae virtus[35] was not the main quality of the Duke of Burgundy.) But 100 of these dresses — or 61% — were, like those of the Savoyard Duke, mostly made of wool. An analysis of the purchases of fabrics shows that the materials used were generally, for the Duke of Burgundy, of good quality for the outer garment, and of lower quality for the lining. Canvas was no longer used for lining at that time, and people generally preferred a black woolen material called ‘gros’ or ‘moindre,’ which cost between 10 and 15 cents for one aune. Linings made of a lower quality cloth, equivalent to those distributed to the lower classes, were also in use at the Burgundy court, but multiple variations made each of these tailor-made pieces unique. Like the Duke of Savoy, then, Philip the Good could on occasion be carefully modest when choosing fabric for his clothing. Thus, woolen cloth at 48 sous per aune was acquired in 1445 and 1447 to line ducal dresses.[36] And sixteen woolen cloth dresses were lined with silk cloths, ephemeral novelties precisely attested during the period considered here. Philip the Good appreciated dresses made exclusively from black fabrics for under and upper garments, with the exception of the pleats which were then ‘felted,’ that is to say, covered with a blanket. But we have seen that some dresses were also ‘felted’ with black fabrics, giving the ducal garments a monochromatic appearance even in the smallest details.

This supremacy of black goes hand in hand with a steady attempt at innovation, as the court became central to changes in clothing shapes and materials, and as courtiers competed for luxury with the ducal person as well as competing with the duke for the know-how of tailors. Among these innovations in fashion, Philip the Good appreciated the exclusively black dresses, in under and over garments, from the fabric to the fur. Lamb’s wool-filled dresses represent just over 20% of the total, while marten ‘zibelines’ represent 67%. The latter were the most popular in a resolutely luxurious costume. Lamb’s wool was appreciated for its darkness, and probably also because, for less luxurious wool cloth dresses, it was cheaper than marten zibelines.[37] For the rest, the comparison with the Duke of Savoy shows statistically that the Duke of Burgundy had a definite penchant for beautiful and rich outfits, and in this sense, succumbed more often to fashion than to austerity: ‘He dressed himself with grace,’ as Georges Chastellain suggests, ‘but in a rich way, and at each change of weather, he changed his clothes with men.’[38]

Apart from a few well-identified and particularly rich pieces, it is difficult to distinguish in his wardrobe a garment that could be described as ‘private.’ His activities, above all, made him a public figure who had to present himself as such in all circumstances. Olivier de la Marche (1426 – 1502), responsible for recounting the prince’s deeds, agreed with this: ‘thus passed year 48 without any further adventure, and part of year 49; and made the Duke great, dear and great feasts in his good towns, where he was much loved, and willingly wanted.’[39] Even his gowns in which to get up at night, which might be considered private, looked stylish. Thus, the material, distinguishing between woolen cloth and silk cloth, was not a valid criterion of private/public differentiation, but rather a witness of the prince’s preferences as much as a means of varying his outfits.

In his obituary of Philip the Good, Georges Chastellain supports the possibility that Philip the Good simply liked black for reasons of style and spectacle. In the obituary, Chastellain does not suggest a religiosity in the prince that extended beyond what was expected of a Christian prince.[40] He praised his commitment to the crusade and his fidelity to the Pope, but in the organization of Chastellain’s chronicle, these last two points were closer to strategic choices than a matter of ‘his condition, his morals, and his many natural virtues.’[41] So, posthumously, Philip the Good appeared to be acting more or less as was expected of him, and the obituary did not report his black clothing as a sign of particularly ascetic religious feeling.

The dresses of the Duke of Burgundy, even of woolen fabrics, do not necessarily reflect temperance, sobriety, or even austerity, attributes that have often been attributed to white and black colours. The colours of modesty and poverty were, on the contrary, rather dull — even undyed or indeterminate, while the tones of wealth were dense, deep, and ‘true.’ It was here that the differences were played out much more than in the colours themselves.[42] Philip the Good wore a rich, dense, luxurious black, in keeping with his image as a powerful prince who appreciated the richness of life, far removed from any ‘severity’ that some authors have too quickly attributed to him.

Doing Politics in Black?

Philip the Good willingly committed large sums to courtly spectacle, especially when the court went on tour. Every movement of the court was carefully prepared, since these trips were public shows par excellence, in which the court put itself on view for its subjects. Particular efforts were made regarding the parade clothing, in their shape, their richness, and in the visual rendering of the whole. In 1435, during the Treaty of Arras, the Duke had a series of huques, or mantles, made in a grey and black cloth for himself, some of the great officers, and French princes, including Charles de Bourbon, Arnaut d’Egmond, the Duke of Gueldre, Count Arthur de Richemont. Covered with goldsmith’s work and embroidered with white and blue crosses, these processional outfits symbolized a new-found understanding of the post-treaty political situation. These identical huques signified that the Burgundian and French ambassadors, by their costume, had sealed their new alliance were willing to walk in the same direction against the English. They also allowed the Duke of Burgundy, supplier and therefore master of the choice of decor, to again place himself as a power in his own right in the treaty. Upon the arrival of the French, he had not failed to position himself at the same protocol level as the Duke of Bourbon and the Count of Richemont, but the richness of the costume displayed by the Duke of Burgundy completed to perfection the reputation of opulence of his states.[43] Along with his own clothes, Philip the Good also standardized the outfits he provided to his officers.

The ducal livery underwent an evolution over the course of the 1430s. In the fifteenth century, black and grey had become highly valued colours, not only in fashion, but also in politics. The livery dresses of Philip the Good still associated these two colours with the Treaty of Arras (1435), as well as with the wedding of Jean d’Etampes in January 1436. In 1437, a meeting was held between the Duke of Burgundy and his prisoner, Duke Jean de Berry, to negotiate the release of the latter. A statement from the painter Hue de Boulogne tells us about the preparations to be made for the jousting that accompanied the festivities, mentioning the golden harnesses and lavishly painted covering, saddle, barding and noses for the horses.[44] During this game, which had a grey theme, the two dukes seem to have agreed to distinguish the colours of their respective liveries: whereas before they both used the grey/black combination, Philip took the black, and Jean kept the grey. Later, Philip the Good’s livery was only available in black.

Emphasizing the centrality of black to the world of court politics, pages, grooms, and footmen received black dresses at the Treaty of Lille (28 January 1437). The outfits of the archers were also changed during this period, at the expense of the colour grey. Grey did not reappear at the court of Burgundy until 1454, on the occasion of the pheasant banquet. The shock was significant enough to be notable in the mind of the Chronicler Jacques du Clercq (ca.1424 – ca. 1468),[45] who insisted that these colours had not been worn at the court of Burgundy for sixteen years; this was undoubtedly more to note the exception than to signify a step backwards.

This episode well illustrates the significantly visual conception of appearance at the Burgundian court, in which the costume played a particularly important role. To our modern eyes, it appears perhaps surprising that clothing was a subject of serious consideration for medieval rulers, yet the same was true during the reign of Charles VI when rival princes quarreled over clothing motives.[46] In this sense, the Burgundian prince’s choices were part of a general movement across Europe in which the appearance of clothing was an integral part of the public performance ‘program.’ Each of Philip the Good’s appearances was thought out and elaborated according to the interlocutor or event, the precise message he wished to convey. In the early 1430s, for example, the duke adopted the Dutch costume at the very moment when he was seeking to position himself as legitimate ruler of the county he had inherited. Similarly, between September and November of the same year, the wardrobe valet Haine Necker, who may have followed the duke to Holland, was commissioned to transform and repair two doublets, and to make four dresses, two doublets, and a huque in velvet cloth, which were perhaps intended for the staging of princely power.[47] For the same purpose, he wore the Brabant dress when he visited his new Brussels subjects whom he had just inherited.

Philip the Good also sought during this period to be accepted by his subjects as the new Duke of Brabant, whose inheritance had been confirmed to him on 5 October 1430. For him, this meant more, and more appropriate, clothing. In June 1432, he traveled to the Duchy of Brabant between Antwerp, Mechelen, Brussels, and Ghent, before staying in his summer residence in Hesdin. During this period, Necker made two Brabant-style dresses. Chaperons were provided to form a matching ensemble. Dresses in this fashion were again made the following year by Philip’s tailor. Philip the Good was staying in Brussels at the beginning of the year, before heading to Bruges in early March. Three black dresses would be worn during his stay with his new subjects.

Apart from the timeliness of his fashion choice, Philip the Good also dressed to evoke the timelessness of his family and rank. If we could make another analogy between iconography, symbolism, and reality, why not see in the character of Philip the Good the living incarnation of the ‘Great Lion of Flanders’ displayed on the arms of the county of Flanders, emblazoned with a proud black lion in sand and gold [Figure 4]. Such a reading fits the historical context, as the period 1436-1437 appears to have been diplomatically delicate in the relations between Philip the Good and his subjects in Flanders, in particular in Bruges.[48] Associating his image with the emblem of Flanders was a way for the Duke of Burgundy to consolidate his position as legitimate sovereign in his states, in the face of the strong desire for freedom expressed by cities.[49] The lion was also strongly associated with the image of the knight[50], to which Philip the Good was also very attached. If Chastellain’s eulogy does not mention Philip the Good’s black mourning, it does make him ‘the one who is called the Grand Duke and the Grand Lion’, in connection with the two titles he placed first in his official documents: Duke of Burgundy and Count of Flanders.[51]

As his political alliances changed, so too did his wardrobe. In 1442, for instance, he adopted the fashion of the Bourbon court, considering Charles de Bourbon, husband of a Burgundian princess, as a privileged interlocutor in his rapprochement with the French princes, following the Arras Treaty, signed in 1435.[52] Similarly, at the wedding of Louis de la Viefville and Marguerite de Raineval, the Duke of Bourbon, his two sons, the Count of Nevers, Jean and Adolf de Clèves, each wore a black cloth coat, completely die-cut, a chaperon stuffed with wool, a black tiercelin stitch doublet lined and stuffed with linen, a black satin robe ‘in the new style’ (‘à la nouvelle façon’), fur lined with martens,[53] and finally an Italian huque. For the Duke of Burgundy, the tailor made a chaperon identical to the previous six, which were also made in the new style.[54] Philip asked his wardrobe valet, Necker, to remake the folds of five dresses[55] that had become too small in the new style. From Richard Berbisey, in Dijon, three aunes of (blanchet) were bought, ‘to line two times at the folds in the Bourbonnoise way’ (‘pour doubler deux foiz par les ploiz à la façon bourbonnoise’.[56] Beaujeu, Herald of Arms to Monsignor the Duke of Bourbon, was thanked for having brought twenty felt hats from his master in Dijon.[57] Since this time, it became common to refer to chaperons in the new style or in the Bourbonnaise way. They included at least one thick padded roll filled with deer hair.[58]

The link between the image of the garment — its visual representation in portraits — and the garment worn in life seems, for Philip the Good, particularly strong, and his textile strategy effectively built a durable image or brand, inscribed in his official portraits. Indeed, the Van der Weyden portrait mentioned above [Figure 1] evidently corresponded to the image that the prince wanted to convey.

Later, and as the prince’s taste for illuminated manuscripts developed, Philip the Good was most frequently represented dressed in black, except when he wore his Golden Fleece costume.[59] The dedication scenes particularly reflect this permanence of black[60] [Figures 5, 6 and 7], the most famous being of course that of the Chronicles of Hainaut in 1448 [Figure 8].[61]

Even when the manuscript was made outside the Burgundian states, Philip the Good appears in characteristic black, as in the case of a manuscript painted in Savoy and offered to the duke in the early 1440s.[62] Indeed, the few rare exceptions to this regime of blackness testify more, if we follow Anne Van Buren’s analysis, to the techniques used by the artists to create the scenes. For example, with regard to the dedication scene of Gilles de Rome’s ‘Government of the Princes,’ she proposes that it was made on an identical model to that of the Hainaut Chronicles, without colours. It was at the time of painting that the artist, choosing the colours according to the harmony of his composition, was mistaken in attributing to Philip the Good’s clothes a salmon pink colour.[63]

This curious incident could be considered an iconographical development independent of the duke’s actual clothing habits, but archival data show that the painted portraits of the black-dressed prince correspond with the self-presentation imposed by the duke himself. Odile Blanc recalls that it is necessary to distinguish between the clothing actually worn and the cultivated image of a king who did not permanently wear the attributes of his function (eg. the crown, the fleurs-de-lis), even though these trappings were hallmarks of his political selfhood.[64] On the contrary, Philip the Good took the equation between clothing and representation literally. It should be noted, however, that the representations of the duke in his painted portraits or in the manuscripts are subsequent to the definitive adoption of the colour black in his daily clothing, so his portraits evidently reflect a state of affairs that was perfectly integrated into his daily life.

Thus, the use of black in the portraits and manuscripts representing the Duke of Burgundy cannot simply be described as a matter of iconography because the depicted garments correspond to clothes actually worn. And the account books further emphasize the visual realism of Flemish portrait painters, because they feature clothing of the correct shapes and materials. Consequently, if the authenticity of the clothes is correlated, according to Anne Van Buren,[65] with the extreme resemblance of the faces from one portrait to another, it is also fully confirmed by archival records. For example in 1448, between April 1 and November 30, the ducal tailor delivered five dresses in black silk cloth, the first in figured satin, the second in plain velvet, the third in plain satin, the other two in velvet on black velvet, descriptions compatible with the outfits represented. This correspondence implies that the iconography of miniature portraits was not simply a manuscript fiction, but actually reflected the daily dressing habit of a prince who was particularly concerned about his image and how he was represented. The same remark could be made about the Golden Fleece necklace, whose numerous repairs attested throughout the period show that it was worn very often. Gilles Docquiers recently showed that the necklace represented in Philip the Good’s portraits was undoubtedly very close to the model delivered by Jean Peutin the goldsmith in the early 1430s.[66]

Ultimately, then, the familiar story of the Philip the Good’s pious adherence to black fails to account for the full range of his clothing’s significance. Rather than simple piety or mourning, his immoderate taste for sumptuous black was the result of a progressive construction of a strategic, politically strong image, which was in step with his motto ‘Autre n’aurai.’ The duke played on medieval imagery and a carefully staged princely appearance to transmit his message, which did not prevent him, as we have seen, from playing on shapes, materials and associations to indulge in the pleasures of fashion. Therefore, the quite exceptional and abundant documentation of the Burgundy court’s material culture available today allows us to reconsider the existing historiography concerned with ducal politics and mentalities in the light of these detailed recordings. Philip the Good completely embodied the colour black, both literally and figuratively. He spread black around his court in the chivalrous image of the ‘Great Lion of Flanders.’ He also found an echo among Flemish artists that depicted him according to the mixed artistic expectations of fifteenth century Flemish portraiture, using reality to magnify the symbol.

This is the revised translation of an article first published under the title “La construction d’une image: Philippe le Bon et le noir”, in Se vêtir à la cour en Europe (1400-1815), ed. Isabelle Paresys and Natacha Coquery, Histoire et Littérature de l’Europe du Nord-Ouest 48, Irhis, Ceges, Crcv, Université de Lille 3, Lille, 2012.

Bibliography

Abraham-Thisse, Simonne, “Achats et consommation de draps de laine par l’hôtel de Bourgogne, 1370-1380”, in Commerce, finances et sociétés, XIème XVIème siècle, recueil de travaux d’Histoire médiévale offert à M. le professeur Henri Dubois, Paris, 1994, p. 27-70.

Alexandre-Bidon, Danièle, La mort au Moyen-Age, XIII-XVe siècle (Paris, Hachette, 1998).

A réveiller les morts : la mort au quotidien dans l’occident médiéval, sous la direction de Alexandre-Bidon, Danièle et Treffort, Cécile (Lyon, PUL, 1993).

Beaune, Colette, “Mourir noblement à la fin du Moyen-Age”, dans La mort au Moyen-Age, colloque de l’Association des historiens médiévistes français (Strasbourg, 1975), p. 125-143.

Blanc, Odile, Parades et Parures. L’invention du corps de mode à la fin du Moyen-Age (Paris, Gallimard, 1997).

Buren Hagiopan, Anne (Van), “Artists of volume 1”, et “Dress and costume” dans Les Chroniques de Hainaut (KBR 9242-9244), ou les ambitions d’un Prince Bourguignon (Brepols Publishers, Turnhout, 2000), p. 65-74 , 66 et .p. 111-117.

Delort, Robert, Le commerce des fourrures en Occident à la fin du Moyen Age (vers 1300-vers 1450), (Paris, Ecole Française de Rome, 1978).

Docquier, Gilles, “Le collier de l’ordre de la Toison d’Or et ses représentations dans la peinture des Primitifs flamands”, in Annales de Bourgogne, Tome 80, fascicule 1-2, numéro 317-318, janvier-juin 2008, p. 125-162.

Gaude-Ferragu, Murielle, D’or et de cendres. La mort et les funérailles des princes dans le royaume de France au Bas Moyen Âge (Villeneuve d’Ascq, Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2005).

Hablot, Laurent, “Les signes du pouvoir”, Histoire et images médiévales, thématique n°17, mai-juin-juillet 2009, p. 66-71.

Hablot, Laurent, “Les signes de l’entente. Le rôle des devises et des ordres dans les relations diplomatiques entre les deux de Bourgogne et les princes étrangers de 1380 à 1477”, Revue du Nord, n°345-346, t.84, avril-septembre 2002, p. 319-341.

Hablot, Laurent, La devise, mise en signe du prince, mise en scène du pouvoir. L’emblématique des princes en Europe à la fin du Moyen-Age, (Turnhout, Brepols, 2009).

Harvey, John, Des hommes en noir. Du costume masculin à travers les siècles, (Paris, Abbeville, 1998) (traduit de l’anglais, 1995).

Jolivet, Sophie, “La construction d’une image: Philippe le Bon et le noir (1419-1467)”, Apparence(s) [Online], 6 | 2015, Online since 25 August 2015, Connection on 11 July 2020. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1307

Jolivet, Sophie, Pour soi vêtir honnêtement à la cour de monseigneur le duc : costume et dispositif vestimentaire à la cour de Philippe le Bon, de 1430 à 1455. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université de Bourgogne, 2003. Français. ⟨tel-00392310⟩

Jolivet, Sophie, “Les dépenses de deuil par l’hôtel de Philippe le Bon : une conception familiale et hiérarchique de la mort”, in Mourir à la cour, Normes, usages et contingences funéraires dans les milieux curiaux à la fin du Moyen-age et à l’Epoque moderne, Cahiers Lausannois d’histoire médiévale, Université de Lausanne, 2017, pp.47-61.

Jolivet, Sophie, “Le phénomène de mode à la cour de Bourgogne : exemple des robes de 1430 à 1442”, Revue du Nord, n°365, avril-juin 2006, p.331-346.

Jolivet, Sophie, “Se vêtir pour traiter : données économiques du costume de cour dans les négociations d’Arras en 1435”, Annales de Bourgogne, t. 69, 1997, pp.273-275.

Lecuppre-Desjardin, Elodie, La ville des cérémonies, Essai sur la communication politique dans les anciens Pays-Bas Bourguignons, (Turnhout, Brepols, 2004.)

Page, Agnès, Vêtir le Prince, tissus et couleurs à la Cour de Savoie (1427-1447), (Université de Lausanne, 1993).

Paviot, Jacques, “Éléonore de Poitiers, Les États de France (Les Honneurs de la Cour) [nelle édition]”, dans Annuaire-Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de France, 1996, p. 75-137.

Pastoureau, Michel, Noir, Histoire d’une couleur (Paris, Seuil, 2008).

Pastoureau Michel, Une histoire symbolique du Moyen Age occidental (Paris, Seuil, 2004).

Polini, Nadia, La mort du Prince, rituels funéraires de la Maison de Savoie (1343-1451), (Lausanne, 1994).

Schnerb, Bertrand, L’État bourguignon (Paris, Perrin, 1999).

Slanicka, Simona, Krieg der Zeichen. Die visuelle politik Johanns ohne Furcht und der armagnakishe-burgundische Bürger krieg (Göttingen, 2002).

Sommé, Monique, “Le cérémonial de la naissance et de la mort de l’enfant princier à la cour de Bourgogne au XVe siècle”, dans Fêtes et cérémonies au XIVe et XVe siècles, publications du centre européen d’Etudes bourguignonnes, n°34, Neuchâtel, 1994, p. 87-103.

Taddei, Ilaria. S’habiller selon l’âge. Les lois somptuaires florentines à la fin du Moyen Âge. Le Corps et sa parure. The Body ans Its Adornement, 15, SISMEL, 2007, Micrologus, pp.329-351.

Pastoureau, Michel, Une histoire symbolique du Moyen Age occidental (Paris, Seuil, 2004), p. 49-64.

This is the revised translation of an article first published under the title “La construction d’une image: Philippe le Bon et le noir”, in Se vêtir à la cour en Europe (1400-1815), Paresys Isabelle, Coquery Natacha (éditeurs), Collection “Histoire et Littérature de l'Europe du Nord-Ouest” n°48, Irhis, Ceges, Crcv, Université de Lille 3, Lille, 2012. Thanks to Luke O'Shaughnessy for his review.

[1] Calmette, Joseph, Les grands ducs de Bourgogne (Paris, Albin Michel, 1949), p. 312, Bourassin, Emmanuel, Philippe le Bon, le grand lion des Flandres (Paris , Tallandier, 1983), p. 34.

[3] Jugie, Sophie “Les portraits des ducs de Bourgogne”, in Images et représentations princières et nobiliaires dans les Pays-Bas Bourguignons et quelques régions voisines (XIVe-XVIes.), Rencontres de Nivelles-Bruxelles (26-29 septembre 1996), publications du centre européen d’études bourguignonnes, n°37, 1997, p. 49-86.

[4] Huizinga, Johan, and Lem, Anton (van der), Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen: studie over levens- en gedachtenvormen der veertiende en vijftiende eeuw in Frankrijk en de Nederlanden, 2018 (1919, 1st ed. H.D. Tjeenk Willink, Haarlem), 68-69.

[5] Jolivet, Sophie, Pour soi vêtir honnêtement à la cour de monseigneur le duc : costume et dispositif vestimentaire à la cour de Philippe le Bon, de 1430 à 1455. Sciences de l'Homme et Société. Université de Bourgogne, 2003. Français. ⟨tel-00392310⟩

[6] A réveiller les morts : la mort au quotidien dans l’occident médiéval, sous la direction de Alexandre-Bidon Danièle et Treffort, Cécile (Lyon, PUL, 1993) ; Alexandre-Bidon, Danièle, La mort au Moyen-Age, XIII-XVe siècle (Paris, Hachette, 1998) ; Polini, Nadia, La mort du Prince, rituels funéraires de la Maison de Savoie (1343-1451), (Université de Lausanne, Lausanne, 1994) ; Beaune, Colette, “Mourir noblement à la fin du Moyen-Age”, in La mort au Moyen-Age, colloque de l’Association des historiens médiévistes français, Strasbourg, 1975, p. 125-143, Sommé, Monique, “Le cérémonial de la naissance et de la mort de l’enfant princier à la cour de Bourgogne au XVe siècle”, in Fêtes et cérémonies au XIVe et XVe siècles, publications du centre européen d’Etudes bourguignonnes, n°34, Neuchâtel, 1994, p. 87-103 ; Gaude-Ferragu, Murielle, D'or et de cendres. La mort et les funérailles des princes dans le royaume de France au Bas Moyen Âge, (Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, Villeneuve d'Ascq, 2005).

[7] Pastoureau, Michel, Noir, Histoire d'une couleur (Paris, Seuil, 2008) ; Harvey, John, Des hommes en noir. Du costume masculin à travers les siècles (Paris, Abbeville, 1998) .(traduit de l'anglais, 1995)

[8] For the reign of Philip the Good, the main chroniclers close to the court were Enguerrand de Monstrelet, Chronique, éd. Douët-d'Arcq, 1857-1862 ; 6 v., Jean Le Fèvre de Saint-Rémy, Mémoires, éd. François Morand, 1876-1881, 2 vol., Matthieu d’Escouchy, Chronique, éd. Du Fresne de Beaucourt, 1863-1864, 3 vol., Jacques du Clerq, Mémoires, éd. Reiffenberg, 1835-1836, Georges Chastellain, Oeuvres, éd. Kervyn de Lettenhove, 1863-1866, 8 vol., Olivier de La Marche, Mémoires, éd. Beaune et d'Arbaumont, 1883-1888, 4 vol.

[9] Mollat M., Favreau R., Fawtier R., Comptes généraux de l’Etat bourguignon entre 1416 et 1420, Paris, 1976, vol. 1, introduction p. XLI et XLII

[10] Sophie Jolivet, Pour soi vêtir honnêtement, op. cit., p. 21-33

[11] Bonenfant, Paul, Philippe le Bon, sa politique, son action (Louvain la Neuve, De Boeck, 1996), particularly “Les traits essentiels du règne de Philippe le Bon”, p. 3-18 and “Du meutre de montereau au traité de Troyes”, p. 105-336. Voir aussi Jean Favier, La guerre de cent ans (Paris, Fayard, 1980), p. 453.

[12] Huizinga, Johan, L'automne du Moyen-Age (1932, Paris, rééd Petite bibliothèque Payot, 1995), p.53

[13] Calmette, Joseph, Les grands ducs de Bourgogne (Paris, Albin Michel, 1949), p. 312 ; Schnerb, Bertrand, Jean Sans Peur, le prince meurtrier (Paris, Payot, 2005); chapitre 41 : “Le deuil et la vengeance”, p. 699-710

[14] Pastoureau, Michel, Noir, Histoire d'une couleur (Paris, Seuil, 2008), p. 101.

[15] Archives départementales de la Côte-d'Or, B. 1508, f° 126: “pour une livrée que mon dit seigneur de Bourgogne fist naguaires quant il dona a disner en son hostel d'Artois a Paris aux ambassadeurs du Roy d'Angleterre”.

[16] See the chapters on the purchase of silk sheets and wool sheets and the preparation of the accounts of the reign of Philip the Bold (from 1396 onwards: ADCO B. 1511; B. 1514; B. 1517; B. 1517; B. 1519; B. 1521; B. 1526; B. 1532; B. 1538). See also Abraham-Thisse, Simonne, “Achats et consommation de draps de laine par l'hôtel de Bourgogne, 1370-1380”, in Commerce, finances et sociétés, XIème XVIème siècle, recueil de travaux d'Histoire médiévale offert à M. le professeur Henri Dubois, Paris, 1994, p. 27-70.

[17] Three accounts of his expenses as Earl of Nevers have been kept at the ADCOs: B. 5518 (1 June 1498-31 December 1498 and 1 January 1419-31 December 1420); B. 5519 (1 January 1401-31 December 1402); B. 5520 (1 January 1403-30 June 1405); see Léon Mirot, Jean-Sans Peur de 1398 à 1405, d'après les comptes de sa chambre aux deniers (Paris, 1939, extract from l'annuaire-bulletin de la Société de l'histoire de France, année 1938)

[18] Accounts of the “recette générale de toutes les finances” consulted: Archives départementales du Nord B. 1878 ; B. 1894 ; B. 1897 ; B. 1903; ADCO B. 1547 ; B. 1554 ; B. 1556 ; B. 1558 ; B. 1560 ; B. 1562 ; B. 1572 ; B. 1576 ; B. 1601 ; B. 1603

[19] Archives départementales du Nord, B 1920, published in Robert Favreau, Michel Mollat, Robert Fawtier, Comptes généraux de l’Etat bourguignon entre 1416 et 1420 (Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1976), 6 vol, III, 1403-1404.

[20] Guénée, Bernard, L’Occident au XIVe et XVe siècle, Les Etats (Paris, PUF, 1998), p. 150.

[21] Taddei, Ilaria, “S'habiller selon l'âge. Les lois somptuaires florentines à la fin du Moyen Âge”, in Le Corps et sa parure. The Body and Its Adornement, Micrologus 15, SISMEL, pp.329-351, 2007.

[22] Kruse, Holger, Paravicini, Werner(Hg.), Die Hofordnungen der Herzöge von Burgund. Band 1: Herzog Philipp der Gute 1407–1467, Instrumenta, 15,1 (Ostfildern, Thorbecke, 2005)

[23] Paviot, Jacques . “Éléonore de Poitiers, Les États de France (Les Honneurs de la Cour) [nouvelle édition]”, in Annuaire-Bulletin de la Société de l'Histoire de France, 1996, p. 75-137

[24] Theoretical treatises and funeral relations intended to serve as a reference and model are kept in the family archives, for example in the “Statuts de Savoie” written in 1430. Pollini, Nadia, La mort du Prince, op. cit. p. 41

[25] Jolivet, Sophie, “Les dépenses de deuil par l'hôtel de Philippe le Bon: une conception familiale et hiérarchique de la mort”, in Mourir à la cour, Normes, usages et contingences funéraires dans les milieux curiaux à la fin du Moyen-age et à l'Epoque moderne, Cahiers Lausannois d'histoire médiévale, Université de Lausanne, 2017, pp.47-61

[26] Previously, colorful tones testified to the conception that the expression of despair was contrary to the spirit of a religion for which death only means a passage to a better afterlife.

[27] One of the first representations is on the tomb of Sancho Diaz de Carillo, dating from the late 13th century, kept in the Catalan Art Museum in Barcelona. Piponnier, Françoise, “Les étoffes du deuil”, in A réveiller les morts: la mort au quotidien in l’occident médiéval, op.cit, p. 135 à 140

[28] Monstrelet, Enguerrand (de), Chronique,(L. Douët d’Arc éditeur), Paris, Jules Renouard, 1859, t. III, p. 361

[29] Chastellain, Georges, Oeuvres , Paris, Publié par Heussner, 1863, p.43-63 ; 143-145

[30] This aspect is recalled by Piponnier, Françoise, “Les étoffes du deuil”, in A réveiller les morts: la mort au quotidien dans l’occident médiéval, sous la direction de Alexandre-Bidon Danièle et Treffort, Cécile (Lyon, PUL, 1993), p. 137.

[31] ADN, B 1927, f.132

[32] Jolivet, Sophie, Pour soi vêtir honnêtement…, op. cit., p. 689 and following.

[33] Un manteau gris et une robe écarlate furent portés en 1445, un chaperon violet fut réalisé en 1451 (pour le chapitre de la Toison d’Or à Mons), deux vêtements blancs concernaient le costume militaire entre 1449 et 1451, et enfin un manteau et une robe furent portés pour la Toison d’Or de 1451, qui eut lieu à Mons-en-Hainaut., voir Jolivet, Sophie, Pour soi vêtir honnêtement…, op. cit., , p. 689 and following.

[34] Page, Agnès, Vêtir le Prince, tissus et couleurs à la Cour de Savoie (1427-1447) (Université de Lausanne, 1993), p. 61-74.

[35] The period under consideration is from 18 August 1443 to the end of 1447. I could not isolate the dresses made by Haine Necker between August 18, 1443 and May 16, 1447, ADN, B. 1982, f° 229 v°-230 r°.

[36] The principle on which the sumptuary laws of Amédée VIII are based according to Agnès Page.

[37] ADN, B 1988, f. 223 r° ; ADN, B 1994, f. 186 r°-186v, ADN, B 2000, f. 162 r°.

[38] Robert Delort has clearly shown that the fashion for black furs was also a 15th century phenomenon. From the 1390s onwards, martens gradually replaced (but never completely) the other furs. Then around 1420, wild furs of Russian or Nordic origin were strongly competed by domestic pelts of Mediterranean origin, especially lambs. This fur, once humble, became an ornament appreciated by the nobles. Delort, Robert, Le commerce des fourrures en Occident à la fin du Moyen Age (vers 1300-vers 1450) (Paris, Ecole Française de Rome, 1978), p. 484

[39] Chastellain (Georges), “Déclaration de tous les hauts faits et glorieuses aventures du duc Philippe de Bourgogne”, in Splendeurs de la cour de Bourgogne, récits et chroniques (Paris, Robert Laffont, 1995), p.753.

[40] “ainsi se passa l’an 48 sans autre aventure, et une partie de l’an 49; et faisoit le duc grandes chères et grans festimens par ses bonnes villes, où il estoit moult aimé, et voulontiers veu”, La Marche, Olivier (de), Mémoires, Livre premier, chapter XXI (Paris, 1884-1888), p. 432.

[41] Georges Chastellain,« Déclaration …, op. cit., 1995, p.754.

[42] Ibid. , p.752.

[43] Pastoureau, Michel, Noir, histoire d'une couleur, op.cit, p. 100 and following.

[44] Jolivet, Sophie, “Se vêtir pour traiter : données économiques du costume de cour dans les négociations d'Arras en 1435”, Annales de Bourgogne, t. 69, 1997, pp.273-275.

[45] ADN, B 1961, f. 159 r°.

[46] Clerq, Jacques (du), Mémoires sur le règne de Philippe le Bon (Bruxelles, édition du Baron de Reiffenberg, 1835-1836), 4 vol, vol. III, chapitre XV, p. 87

[47] Hablot, Laurent, “Les signes du pouvoir”, in Histoire et images médiévales, thématique n°17, mai-juin-juillet 2009, p. 66-71; Slanicka, Simona Krieg der Zeichen. Die visuelle politik Johanns ohne Furcht und der armagnakishe-burgundische Bürger krieg (La guerre des signes. La politique visuelle de Jean Sans Peut et la guerre civile Armagnacs-bourguignons) (Göttingen, 2002) ; Hablot, Laurent, ”Les signes de l'entente. Le rôle des devises et des ordres dans les relations diplomatiques entre les deux de Bourgogne et les princes étrangers de 1380 à 1477”, Revue du Nord, n°345-346, t.84, April-September 2002, p. 319-341; Hablot, Laurent, La devise, mise en signe du prince, mise en scène du pouvoir. L'emblématique des princes en Europe à la fin du Moyen-Age (Turnhout, Brepols, 2009).

[48] ADN, B 1948, f. 300 v°.

[49] Schnerb, Bertrand, L'État bourguignon (Paris, Perrin, 1999), chapter 22: L'état bourguignon face au particularisme urbain, en particulier “le temps des révoltes”, p. 373-379.

[50] Georges Chastellain and J.A. Buchon, Chronique des ducs de Bourgogne, par Georges Chastellain, vol. II–III (Paris: Verdière, 1827), XVII. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6227595m

[50] Georges Chastellain and J.A. Buchon, Chronique des ducs de Bourgogne, par Georges Chastellain, vol. II–III (Paris: Verdière, 1827), XVII. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6227595m

[50] Georges Chastellain and J.A. Buchon, Chronique des ducs de Bourgogne, par Georges Chastellain, vol. II–III (Paris: Verdière, 1827), XVII. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6227595m

[55] Quelques folios plus loin, le drapier Jean de Pognes livra 2,5 aunes de drap noir de Montivilliers au duc pour faire deux chaperons à la nouvelle façon, ADN, B 1975, f. 157 v°.

[55] Quelques folios plus loin, le drapier Jean de Pognes livra 2,5 aunes de drap noir de Montivilliers au duc pour faire deux chaperons à la nouvelle façon, ADN, B 1975, f. 157 v°.

[57] See e.g. the ducal portrait in Les Grandes Chroniques de France, St Petersbourg, Bibliothèque nationale, ms fr Qv VI 1, f° 2, https://vivaldi.nlr.ru/oi000000089/view/#page=, last accessed on 14 May 2021.

[57] ADN, B 1975, f. 158; further on this is specified: “pour doubler de cinq doubles par hault et de deux par le dessous à la façon bourbonnoise les plis de deux robes”, ADN, B 1975, f. 158v°

[59] For example, for a small head covering for horse riding and another big French hood with a long cornet, padded with a large roll of cloth stuffed with deer hair in the Bourbonnaise way, ADN, B 1982, f. 229 v°

[61] For example : Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms fr 9087, f° 1; Vienne, bibliothèque nationale d'Autriche, ms 2549, f° 1 ; Bruxelles, Bibliothèque nationale de Belgique ms 9092, f° 1

[62] Bruxelles, BNB ms 9242, f° 1,

[63] Bruxelles, BNB ms 9466, f° 1

[64] Buren Hagiopan, Anne (van), “Artists of volume 1”, and “Dress and costume” in Les Chroniques de Hainaut (KBR 9242-9244), ou les ambitions d’un Prince Bourguignon, ( Turnhout, Brepols, 2000), p. 65-74 , 66 et .p. 111-117.

[65] Blanc, Odile, Parades et Parures. L’invention du corps de mode à la fin du Moyen-Age (Paris, Gallimard, 1997), p. 13

[66] Buren-Hagiopan, Anne (van), “Dress and Costume”, op. cit., p. 112 Docquier, Gilles, “Le collier de l'ordre de la Toison d'Or et ses représentations dans la peinture des Primitifs flamands”, in Annales de Bourgogne, Tome 80, fascicule 1-2, numéro 317-318, janvier-juin 2008, p. 125-162