Many types of wood contain resins, ranging from softwood to hard wood. Especially coniferous trees are known for their high content of resins which made them interesting for production of pitch and tar, and as sources for the production of black soot pigments. Resins are an additional source of carbon and therefore resin-rich woods produce more soot than woods without resin. Some resins were famous for their fragrance, like frankincense, myrrh and mastic. They were highly esteemed import products. Most resins have a medical application and therefore are included in medical treatises. They were sold in pharmacies.

Soot of frankincense Figures 13a, 13b Quote 7 / Recipe 6

“Item. Mache eine grosses Licht von Unschlitt (Talg) in einem Tiegel und zünde das an und spalte ein Stäbchen auf und tue Weihrauch dazwischen und halte das unter ein Becken was darüber gestürzt ist und brenne den Weihrauch in dem Lichte, so setzt sich Russ an dem Becken ab. Den streiche mit einer Feder ab und nehme Harz von Arabien [Gummi Arabicum] und lege das in Wasser das es sich auflöse und mische das dann darunter, das wird einer schöne wunderbare Fabe, mit der Du färben kannst was Du willst.”[1]

A precious source of soot, closely related to monastic use, was olibanum, frankincense. This fragrant resin is a product of trees of the genus Boswellia and had to be carried all the way from the Arabian Peninsula, north-east Africa or India (Fig. 13a,b). Frankincense is mentioned in two German treatises written in the second half of the fifteenth century. The recipes prescribe to fill a bowl with either animal fat[2] or oil[3], add a wick, and ignite it. The compiler of Liber illuministarum, working in a monastic environment, suggests putting a piece of frankincense ‘alz groß alz ain halbs ay’[4] onto the wick of an oil lamp. This size is rather large for a natural resin, and the wick must be considerably thick to keep such a large piece in place during burning. The cited German manuscript, HS 181503, comprises instructions for another procedure: to split a rod, insert a piece of frankincense, hold this over the flame. In both cases a bowl is installed on top to collect the formed soot. After cooling, the soot is swept into a clean pot with a feather.

Soot of coniferous resin Figures 14a, 14b Quote 8 / Recipe 7

“Item flamswart toe maken. Neem dycke lemmyt van groeven tauwe als eenswanen veder ende cleme daer harse om als een eynde van I kersen unde settet under I becken ser scoen ghescurt, ghestolpet op iij halve backen steen ende wil mens vole hebben so mach men om dat kersken legghen iiij stacke herse in een kannenschaert off in een latel panne ende latet wtbemen ende dan vechtet van den becken ende wrijstet wal myt watter also langhe al rubrijck ende steeckt op een krijt ende lattet drugen ende doet in een busse.”[5]

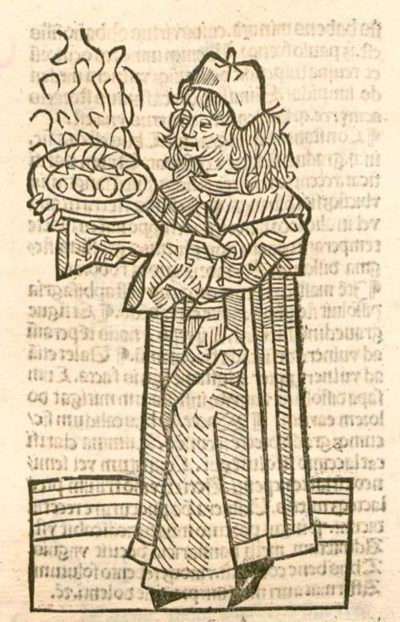

Less exotic, but interconnected with frankincense, is the resin of many European trees. Especially coniferous trees are resin-rich, they even contain distinctive resin canals. Resin is naturally exuded by injured trees; it seals their wounds and has a protective function (Fig. 14a). By deliberately cutting the bark of trees, a substantial amount of protruding resin can be collected throughout a year. The resin requires further cleaning by melting and straining. It was used in as incense and in medicine and was depicted in early printed medical treatises like the Hortus sanitates, an incunabulum printed in Mainz in 1497 (Fig. 14b). Burning the resin of pine, spruce or fir trees produces a soot-rich smoke, an excellent precondition for pigment production. In 1431 le Begue included an antique recipe into his compilation of copied art-technological treatises, where resin is burnt indirectly on hot tiles to obtain a black pigment.[6] Resin could also be kneaded around a wick, placed between additional resin in a fire-proof earth ware and ignited. By completely burning the resin, the soot was collected on the surface of a clean bowl that was set upside down on three bricks, as the cited recipe in the Kölner Musterbuch (1450) written by hand in Northeastern Middledutch reveals.

Larger-scale soot production from resin of coniferous trees began in Europe with the introduction of book printing.[7] This process was carried out in specifically-built small shacks, in which cauldrons full of resin or pitch were placed, ignited, and the evolving soot collected on stretched animal skins or canvas lined with paper.[8] In this way, larger amounts of what was then called noir de fumée leger or noir de Paris were made. This product was misleadingly also sold under the name lampblack.[9]

Soot of pitch and tar (Figures 15a, 15b)

In wood-rich areas of Scandinavia, Central Germany and France resin of coniferous wood was extracted on large-scale by dry distillation. Wood was stacked in specifically-built ovens with an external heat source.[10] The high temperatures caused the resins within the wood to melt, and they were collected as so-called pitch. Viscous pitch was further heated to produce the nearly solid, black-colored tar. Tar and pitch render all kinds of materials waterproof and therefore were abundantly available, especially in harbor cities, proving indispensable for the shipbuilding industry. Both materials could be burnt directly in pans, as described above under soot of coniferous trees/noir de Paris.

Soot of Pix Burgundica (Fig. 16a, 16b)

Burgundy pitch is a specially prepared resin of the spruce (genus Picea). It is unknown if it was available in the fifteenth century, but is included here as one potential source for soot making in Burgundy.

Soot of colophony Figure 17

A particular fraction of pine resin is further processed to Greek pitch, colophony, which was used after 1450 for producing soot for printing inks.[11]

Soot of torches Figure 18 Quote 9 / Recipe 8

“To make a fuime black called Sable. Take a cleane latten basen, and hold a burning torch under it, untill the botome be black, and then take of that blacke, and temper it with glayre or with Gumme water, and so worke with it.” [12]

The flammability of tar and pitch made them ideal for impregnating the tops of torches. The Montpellier Liber diversarum arcium refers to soot of pine-torch collected in a cuprous vessel, stored in a well folded page, and used as pigment for preparing a black ink.[13] It is assumed that torches were a rather easily available source for preparing black pigments. Several publications of the sixteenth and especially the seventeenth century include soot of torches as a watercolor pigment, for example, the recipe quoted at the beginning of this section from the book “The Art of Limming”, published in 1596.

[1] “Item Make a big light from tallow in a pan and light it and split a stick and put incense in between and hold it under a basin which is put over it and burn the incense in the light, so soot will settle on the basin, brush it off with a feather. Take resin from Arabia (gum Arabic) and put it in water that it dissolves and then mix it with it, it becomes a beautiful, wonderful color with which you can color whatever you want.” Hs 181503. 1451-1500. Nuremberg, Germanisches National Museum, Hs 181503: fol. 1r.

[2] Hs 181503. 1451-1500. Nuremberg, Germanisches National Museum, Hs 181503: fol. 1r.

[3] Liber illuministarum. 1450/1500-1512. Munich, Staatsbibliothek, MS. Germ. 821: fol. 28r,v / 143r. In: Bartl et al. 2005. Der “Liber illuministarum” aus Kloster Tegernsee: p. 93, 267. Includes the same recipe in both of its parts.

[4] The size of half an egg, Liber illuministarum (1450 / 1500-1512): fol. 28r and 143r. In: Bartl et al. 2005. Der “Liber illuministarum” aus Kloster Tegernsee: p. 92-93, 266-267.

[5] “Item to make soot-black. Take a thick wick from coarse ropes like a swan feather, and pinch resin around it like a candle and put it under a basin that has been very neatly scrubbed, overturned on 3 half bricks; and if you want to have the whole thing [vole = complete?], you can place iiij pieces of resin on a jug or a latel [?] pan around the candle and let it fully burn, and then sweep it off the basin and grind it with water as long as Rubrijk. And put it on chalk and let it dry and put it in a box.” In: Kölner Musterbuch. 1490. Köln, Historisches Archiv der Stadt, Best. 7010 (Wallraf) 293: fol. 7r.

[6] Jehan le Begue (1431), citing Eraclius ‘De coloribus et artibus Romanorum‘ liber III. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 248.

[7] This process should be not mistaken for the soot production from resinous wood which took place directly in regions rich in hardwood. Burning residues of resins, tar or pitch could be carried out elsewhere.

[8] Tingry. 1804. The Painter and Varnisher’s Guide: p. 51.

[9] Krünitz. 1820. Oekonomisch-Technologische Encyklopädie, Vol. 128: p. 728-729.

[10] An excellent source on the historic production of pitch and tar is Wiesenhavern. 1793. Abhandlung über das Theer-oder Pechbrennen.

[11] Marciana Manuscript. 1503-1535. Biblioteca Marciana di Venezia, It.III. 10. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 2: p. 610, 618.

[12] Anonymous. 1596. A Very Proper Treatise Wherein Is Breefely Set Forth the Art of Limming: fol. 6v, 7r.

[13] The quote might also refer to a piece of pine wood, which was a common torch-like illuminant, not impregnated with pith or tar because it contained enough resin to burn effectively (ger: Kienspan). Clarke. 2011. The Medieval Painter’s Materials and Techniques: The Montpellier Liber Diversarum Arcium: p. 106, 251 (§1.6.2).

'De coloribus et artibus Romanorum' liber III. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries

[1] “Item Make a big light from tallow in a pan and light it and split a stick and put incense in between and hold it under a basin which is put over it and burn the incense in the light, so soot will settle on the basin, brush it off with a feather. Take resin from Arabia (gum Arabic) and put it in water that it dissolves and then mix it with it, it becomes a beautiful, wonderful color with which you can color whatever you want.” Hs 181503. 1451-1500. Nuremberg, Germanisches National Museum, Hs 181503: fol. 1r.

[1] “Item Make a big light from tallow in a pan and light it and split a stick and put incense in between and hold it under a basin which is put over it and burn the incense in the light, so soot will settle on the basin, brush it off with a feather. Take resin from Arabia (gum Arabic) and put it in water that it dissolves and then mix it with it, it becomes a beautiful, wonderful color with which you can color whatever you want.” Hs 181503. 1451-1500. Nuremberg, Germanisches National Museum, Hs 181503: fol. 1r.

[1] “Item Make a big light from tallow in a pan and light it and split a stick and put incense in between and hold it under a basin which is put over it and burn the incense in the light, so soot will settle on the basin, brush it off with a feather. Take resin from Arabia (gum Arabic) and put it in water that it dissolves and then mix it with it, it becomes a beautiful, wonderful color with which you can color whatever you want.” Hs 181503. 1451-1500. Nuremberg, Germanisches National Museum, Hs 181503: fol. 1r.

[4] The size of half an egg, Liber illuministarum (1450 / 1500-1512): fol. 28r and 143r. In: Bartl et al. 2005. Der "Liber illuministarum" aus Kloster Tegernsee: p. 92-93, 266-267.

[5] “Item to make soot-black. Take a thick wick from coarse ropes like a swan feather, and pinch resin around it like a candle and put it under a basin that has been very neatly scrubbed, overturned on 3 half bricks; and if you want to have the whole thing [vole = complete?], you can place iiij pieces of resin on a jug or a latel [?] pan around the candle and let it fully burn, and then sweep it off the basin and grind it with water as long as Rubrijk. And put it on chalk and let it dry and put it in a box.” In: Kölner Musterbuch. 1490. Köln, Historisches Archiv der Stadt, Best. 7010 (Wallraf) 293: fol. 7r.

[6] Jehan le Begue (1431), citing Eraclius 'De coloribus et artibus Romanorum' liber III. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 248.

[7]

[9] Krünitz. 1820. Oekonomisch-Technologische Encyklopädie, Vol. 128: p. 728-729.

[9] Krünitz. 1820. Oekonomisch-Technologische Encyklopädie, Vol. 128: p. 728-729.

[11] Marciana Manuscript. 1503-1535. Biblioteca Marciana di Venezia, It.III. 10. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 2: p. 610, 618.

[12] Anonymous. 1596. A Very Proper Treatise Wherein Is Breefely Set Forth the Art of Limming: fol. 6v, 7r.

[12] Anonymous. 1596. A Very Proper Treatise Wherein Is Breefely Set Forth the Art of Limming: fol. 6v, 7r.