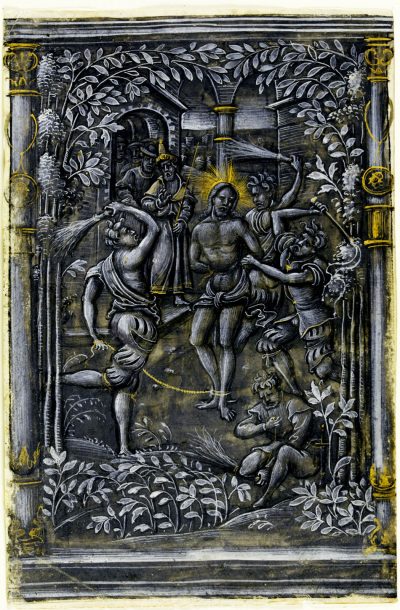

Black stone, black chalk (lapis nero) Figure 36

Already around 1400 Cennini refers to lapis nero, then a new material from the Piemont region, ideal for use as black chalk crayons for drawing. [1] In 1431 le Begue includes lapis niger into his table of synonyms.[2] Black chalk is commonly found close to slate mines and was also applied as a pigment. Albeit in absence of ivory black, it is the most expensive black pigment in the aforementioned Italian pigment price lists published by Spear. Slate deposits are present in today’s Belgium. It would be interesting to determine if it was already available to Burgundian artists as a black drawing medium or pigment, or if they imported it from Italy.

> Graphite, black lead Figure 37a, Quote 21

“To temper blacke Leade: Grynde well blacke Leade with gumme water on a Painters stone, and then put it in a shell to woorke withal. This is a perfite Crane color of it selfe”.[3]

In the first half of the sixteenth century graphite was discovered in Cumberland, England, too late for Burgundian illuminators. The first image of a black lead pencil was published by the Swiss scholar Conrad Gesner in 1565.[4] Shortly after, it is mentioned as a black pigment in the first English printed book on limning, the 1573 published “A very proper treatise wherein is breefely set forth the art of limming”. The anonymous author makes the reader aware that the color obtained is that of the crane, a perceptive observation which is repeated by later authors.[5]

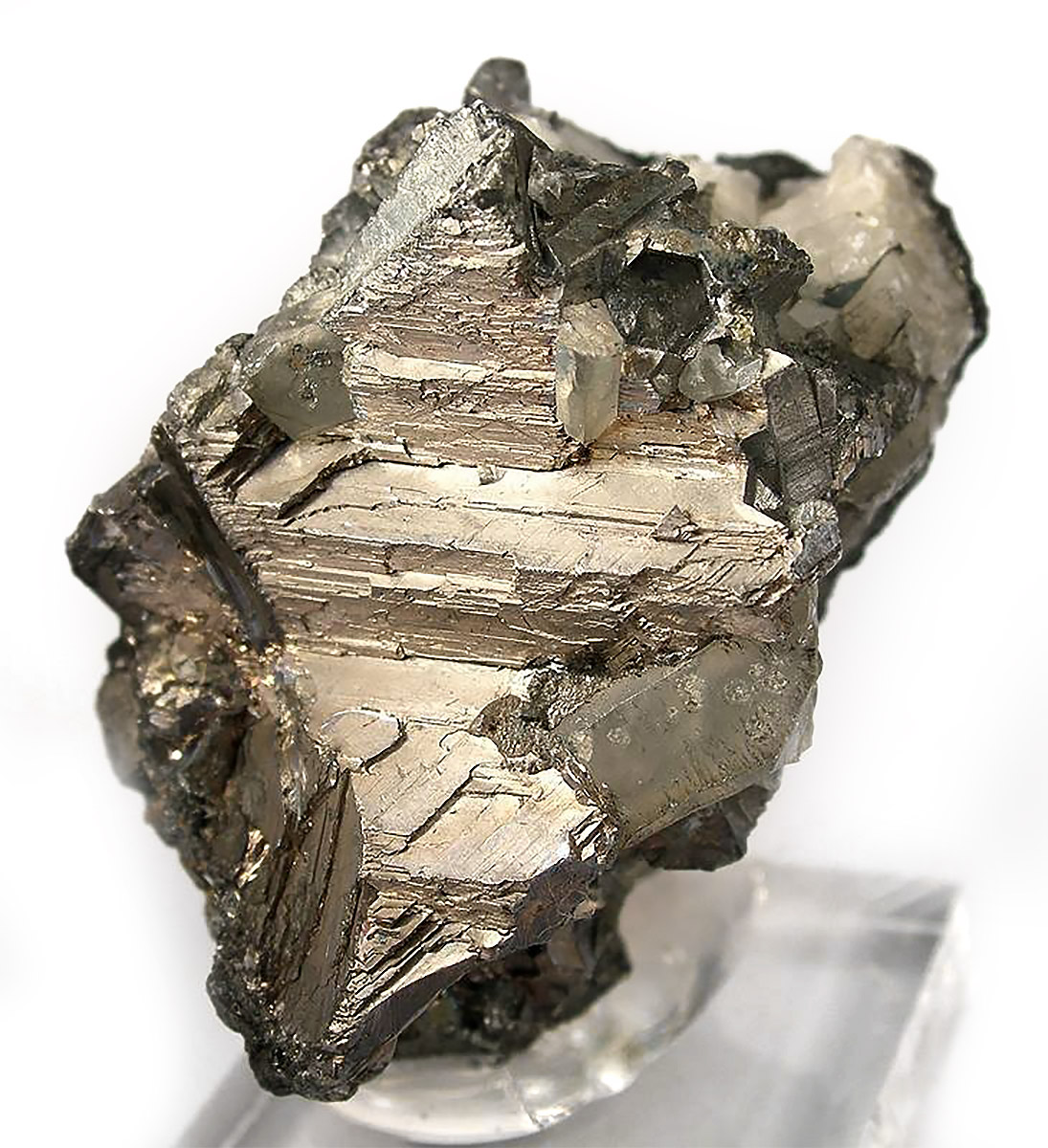

> Antimony black (kohl, Stibium sulfuratum nigrum) Figures 38a, 38b

It is noteworthy that this pigment, while not included in the consulted treatises, was identified in at least two illuminations of different artists active around 1500, namely an Italian miniature by the Pallavicini Master (active in Rome 1492-1507) and in one of five French grisaille miniatures from the Poeme sur la Passion by the Master of Girard Acarie (c. 1530).[6] Antimony (III) sulfide (Sb2S3) is a naturally occurring black-grey colored mineral, stibnite. Stibnite is quite common and found in many European mines. It occurs in paragenesis with many other sulfide minerals, such as orpiment, realgar, cinnabarite, pyrite, and barite, all well-known artist materials. The mineral has been known since ancient times and was used for instance as black eyeliner, especially in the Arab culture, where it is known by the name kohl. Highly regarded by alchemists, widely used in metallurgy and in medicine, antimony black most probably was available to the Burgundian illuminators.

> Bismuth black Figure 39

Bismuth black was identified as granular elemental bismuth in eight illustrations by Jean Bourdichon (1457–1521), an important French manuscript illuminator. These illustrations were spread over three manuscripts dating from the early 1480s to 1515. [7] Bismuth black was not found in the consulted sources as part of an illuminator’s palette. In nature, bismuth occurs either native in its elemental state, or in ores of for instance cobalt, nickel, silver and tin. It is found for instance in Schneeberg, Germany and was discussed by Paracelsus and Agricola in the first half of the sixteenth century.

> Pyrolusite (Maganese(IV)oxide, MnO2) Figure 40

Already used by Neanderthals and found in prehistoric cave and rock art, pyrolusite is a naturally occurring black-grey mineral, and an important ore for manganese. Many deposits are present in Europe. The Montpellier Liber diversarum arcium lists it under ‘De manganese’ as a black color for glass and ceramics. Pyrolusite was identified in a manuscript initial illuminated in Bologna or Rome about 1490-1500.[8] It should be noted that certain umbers show a high pyrolusite content .

[1] Broecke. 2015. Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: A New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription: Chapter 34, p. 55-56.

[2] Le Begue. 1431. BnF MS Latin 6741: fol. 10r, table of synonyms.

[3] Anonymous. 1573. A Very Proper Treatise: f. 6r https://archive.org/details/verypropertreati00lond/page/n4/mode/1up.

[4] Gessner. 1565. De Omni Rerum Fossilium Genere: fol. 104v https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/4362/1/0/.

[5] Bate. 1634. The Mysteryes of Nature and Art: p. 122. https://archive.org/details/mysteryesofnatur00bate/page/122/mode/2up

[6] Ricciardi and Beers. 2016. The Illuminators’ Palette: p. 35.

[7] Trentelman and Turner. 2009. Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon: p. 577–84.

[8] Ricciardi and Beers. 2016. The Illuminators’ Palette: p. 35.

[1] Broecke. 2015. Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: A New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription: Chapter 34, p. 55-56.

[1] Broecke. 2015. Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte: A New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription: Chapter 34, p. 55-56.

[3] Anonymous. 1573. A Very Proper Treatise: f. 6r https://archive.org/details/verypropertreati00lond/page/n4/mode/1up.

[3] Anonymous. 1573. A Very Proper Treatise: f. 6r https://archive.org/details/verypropertreati00lond/page/n4/mode/1up.

[3] Anonymous. 1573. A Very Proper Treatise: f. 6r https://archive.org/details/verypropertreati00lond/page/n4/mode/1up.

[6] Ricciardi and Beers. 2016. The Illuminators’ Palette: p. 35.

[6] Ricciardi and Beers. 2016. The Illuminators’ Palette: p. 35.

[8] Ricciardi and Beers. 2016. The Illuminators’ Palette: p. 35.