Charcoal burns without smoke, because all organic components that could form gasses are already lost during the charring process. Burning charcoal reaches higher temperatures than uncharred wood yields. Therefore, it is of special interest to all professions that require high temperatures like blacksmiths, goldsmiths, lime burners and potters. Charcoal is included in many artisan treatises as fuel for specific purposes.

> Charred wood (Figures 20a, 20b) Quote 10

“Kol Swart. Van houdt colen maekt men een blouw offt grauw swardt / alsmen die wel clijn vrijft, en opt crijt laet verdroogen.”[6]

All types of wood can be processed to charcoal. The initial hardness of the wood is retained after charring. For this reason, oak wood is not recommended as raw material for black pigments.[7] Instead, softer wood species are preferred. In 1431 Le Begue lists carbo in his tabula de vocabulis sinonimis et equivocis colorum, black pigments made from charred wood of willow, poplar, vine and similar soft woods.[8] Other authors just use the generic term charcoal as a source of black pigment, often without specifying the source of wood.[9]

> Charred vine shoots or willow twigs Figures 21a, 21b RECONSTRUCTION

Already in the fourteenth century, the Montpellier Liber diversarum arcium, specifies charred vine (genus Vitis) or willow (genus Salix) as preferred raw materials for the black paint of illuminators. According to Marc Clarke (2011), the black of these chars is referred to in earlier sources as nigrum optimum, “the best black”.[10] Later sources recommend charred wood of willow as well.[11] Crayons made of charred twigs of vine or willow belong to the average toolbox of fifteenth-century artists, perfect tools for (under)drawing. It is known that charcoal crayons break easily and therefore can be effortlessly ground as a source of a black pigment. Tendrils and twigs of vine plants were also burnt directly to obtain a black pigment, however this causes quite a loss of material.

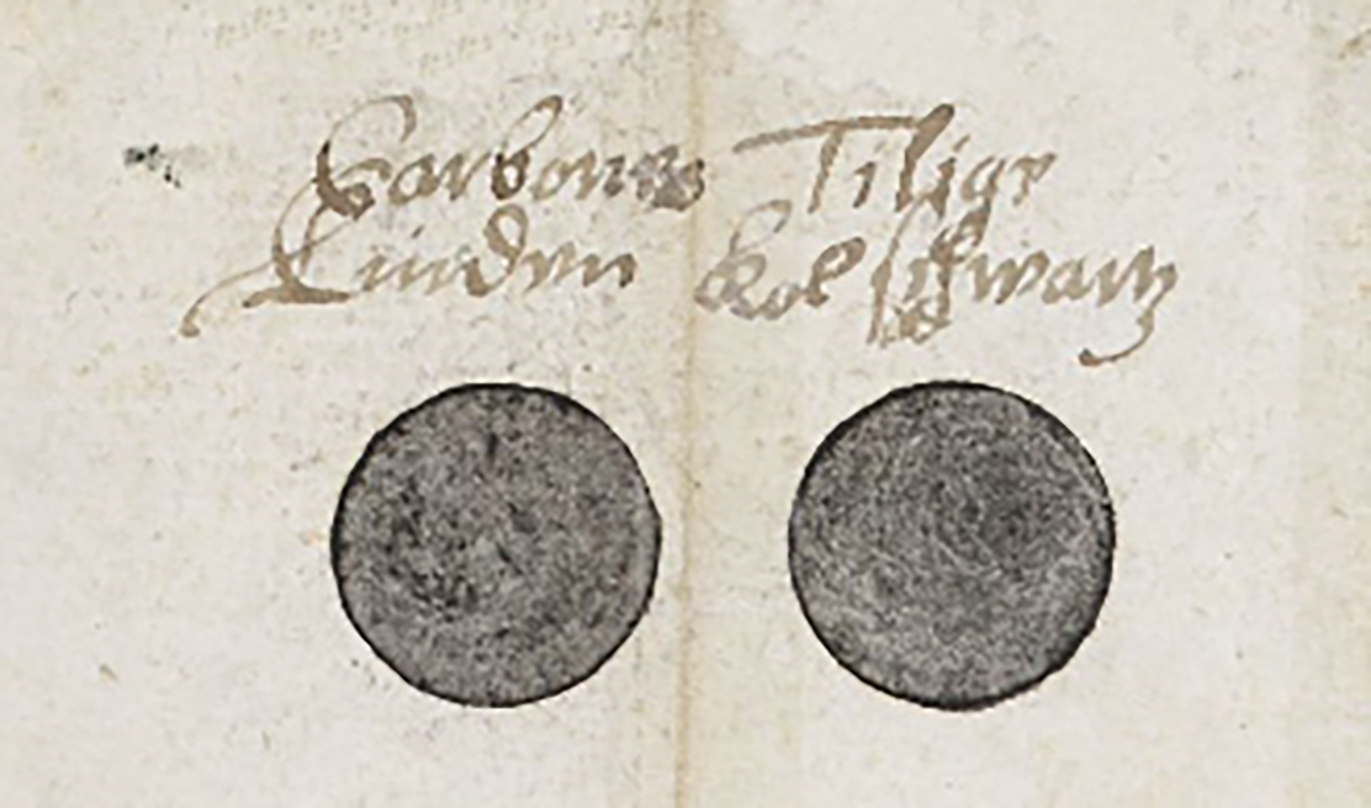

> Linden tree char Color sample 4

The late medieval Liber Illuministarum includes charred linden tree soot, but as a pigment used in primers for gilding, not as black watercolor.[12] A series of Latin recipes in MS Sloane 2052 in an anonymous hand lists carbones seq. Tilius, the charred wood of the linden tree (genus Tilia).[13]

[6] “Coal black. Of charcoal one makes a blue or gray black / rub it well and let it dry on the chalk.” Anonymous. 1600-1650. Schoone consten ende secreten, Rome, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms. Lat. 7279: fol. 25r; see also Braekman. 1994. Antwerpse ‘consten ende secreten’ voor verlichters en ‘afsetters’ van gedrukte prenten: p. 117.

[7] le Begue. 1431. citing Eraclius ‘De coloribus et artibus Romanorum’ liber III. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 138

[8] le Begue. 1431. Paris, BnF, MS Latin 6741: fol. 4v.

[9] Le Begue. 1431. Archerius. De diversis coloribus (1398-1411). In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 300; and Recueil de recettes et secrets concernant l’art du mouleur, de l’artificier et du peintre. after 1579. Paris, BnF, MS fr. 640: fol. 58v, 59v, 63v.

[10] Clarke. 2011. The Medieval Painter’s Materials and Techniques: The Montpellier Liber Diversarum Arcium: p. 105 (§1.5.1A eng., char of willow and vine), 251 (§1.5.1, lat.), 174 (reference to nigrum optimum). See also Reissland. 2014. Why do Artists Prefer Vine or Willow Charcoal?.

[11] Amongst others, Le Begue. 1431. Paris, BnF, MS Latin 6741: fol. 4v, MS Sloane 6284. late sixteenth c. B.M. MS Sloane 6284. In: Harley. 1982/2001. Artists’ Pigments c.1600-1835: p. 157 and Haydocke 1598. A Tracte […] translation of Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo’s Trattato del arte della pittura, scultura ed architettura: 100.

[12] Bartl et al. 2005. Der “Liber illuministarum” aus Kloster Tegernsee: p. 517.

[13] Mayerne. 1620-46. Mayerne Manuscript, London, British Library, MS Sloane 2052: fol. 79v.

[6] "Coal black. Of charcoal one makes a blue or gray black / rub it well and let it dry on the chalk." Anonymous. 1600-1650. Schoone consten ende secreten, Rome, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms. Lat. 7279: fol. 25r; see also Braekman. 1994. Antwerpse ‘consten ende secreten’ voor verlichters en ‘afsetters’ van gedrukte prenten: p. 117.

[7] le Begue. 1431. citing Eraclius 'De coloribus et artibus Romanorum' liber III. In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 138

[8] le Begue. 1431. Paris, BnF, MS Latin 6741: fol. 4v.

[9] Le Begue. 1431. Archerius. De diversis coloribus (1398-1411). In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 300; and Recueil de recettes et secrets concernant l'art du mouleur, de l'artificier et du peintre. after 1579. Paris, BnF, MS fr. 640: fol. 58v, 59v, 63v.

[9] Le Begue. 1431. Archerius. De diversis coloribus (1398-1411). In: Merrifield. 1849. Original Treatises, Dating from the XIIth to the XVIIIth Centuries, Vol. 1: p. 300; and Recueil de recettes et secrets concernant l'art du mouleur, de l'artificier et du peintre. after 1579. Paris, BnF, MS fr. 640: fol. 58v, 59v, 63v.

[11] Amongst others, Le Begue. 1431. Paris, BnF, MS Latin 6741: fol. 4v, MS Sloane 6284. late sixteenth c. B.M. MS Sloane 6284. In: Harley. 1982/2001. Artists' Pigments c.1600-1835: p. 157 and Haydocke 1598. A Tracte […] translation of Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo's Trattato del arte della pittura, scultura ed architettura: 100.

[12] Bartl et al. 2005. Der "Liber illuministarum" aus Kloster Tegernsee: p. 517.

[12] Bartl et al. 2005. Der "Liber illuministarum" aus Kloster Tegernsee: p. 517.