Burgundian illuminators were challenged to express the splendour and strength of Philip the Good’s fashionable appearance in the famous frontispieces of contemporary manuscripts. The precious materiality of colour as a powerful signifier had a long tradition in religious painting and manuscript making, rendering holy figures in vibrant colours made from costly raw materials. As Jenny Boulboullé argued in her essay in this collection, ‘Illuminating Burgundian Black Splendors’, the colour black played an instrumental role in Burgundian politics and was pivotal for the powerful self-expression of Philip the Good. In light of this fact we asked which choices Burgundian illuminators have had to make in order to establish a historically vivid image of their Duke dressed up in luscious black fashion? [Figure 1].

Making black pigment from burnt peach pits with Birgit Reissland, Atelier Building Amsterdam. A film by Katrien Vanagt and Stefano Bertacchini, 2020 ©Serafín Productions for ARTECHNE.

The Burgundian Master Illuminators: Exploring the Archive

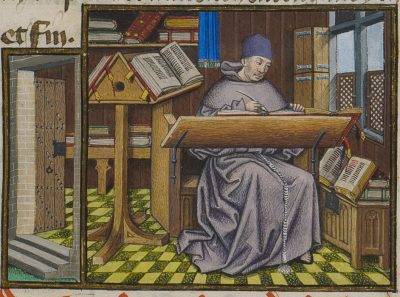

From late antiquity to the Renaissance, book illumination was one of the most important art genres. Illuminating manuscripts was a profession separate from scholarship, calligraphy, rubrication, and bookbinding. The Burgundian court employed excellent scholar-authors like Jean Wauquelin (b. c. 1400 in Picardië – d. 1452 in Bergen), translator of the Chroniques de Hainaut, and Jean Miélot (b. ? in Gueschard – d. 1472 in Lille) who served as secretary to Philip the Good and later to his son Charles the Bold. Not only are the names of these scholars known, but we are also in the fortunate situation to have their portraits. They are shown either during the ceremonial presentation handing over the completed book to the patron in the famous presentation miniatures that became so popular under the dukes of Burgundy, or they are portrayed while working in their studies. A miniature most probably showing Wauquelin is, for instance, situated on a very prominent place on the second folio of the Chroniques de Hainaut Vol. 1 (ms. 9242, fol. 2r, KBR, Brussels), the folio after the famous frontispiece. He is depicted in his study, likely while translating the Latin text of the Chroniques de Hainaut into French [Figure 2].[1]

Reworking an ink recipe for writing on parchment from Simon Andriessen’s Vieruoudich Tractaet Boeck, Campen: Steven Joessen, 1552, fol. xl recto with Birgit Reissland and Jenny Boulboullé, Atelier Building Amsterdam. A film by Katrien Vanagt and Stefano Bertacchini, 2020 ©Serafín Productions for ARTECHNE.

The situation is quite different for Burgundian illuminators. Attribution to a specific illuminator or his workshop commonly raises many questions. For instance while Wauquelin (as translator) and Jacotin du Bois (as scribe) of the first part of the Chroniques de Hainaut are known indeed, the illuminator of its famous frontispiece is still subject of controversial scholarly discussions.[2] Famous illuminators working for the Burgundian court were Jean Le Tavernier (b. ? in Oudenaarde – d. 1462 in ?), Dreux Jehan (b. ? in ? – d. before 1467 in Bruxelles), Loyset Liédet (b. c. 1420 in Hesdin ? – d. after 1484 in Lille) and Guillaume Vrelant (b. ? in Utrecht – d. 1481/82 in Brugge). It is well known that the latter two were paid for working on the illuminations of the second and third volume of the Chroniques de Hainaut, a lucky exception for the rather rare sources available which provide names of commissioned illuminators.[3] Remarkably, the discrepancy between available information on scribes and illuminators is also reflected in the depiction of both professions — while writing scholars and scribes have been pictured relatively often, portraits of illuminators are scarce and — despite their masterful artistic virtuosity — we still lack an image of a Burgundian illuminator.

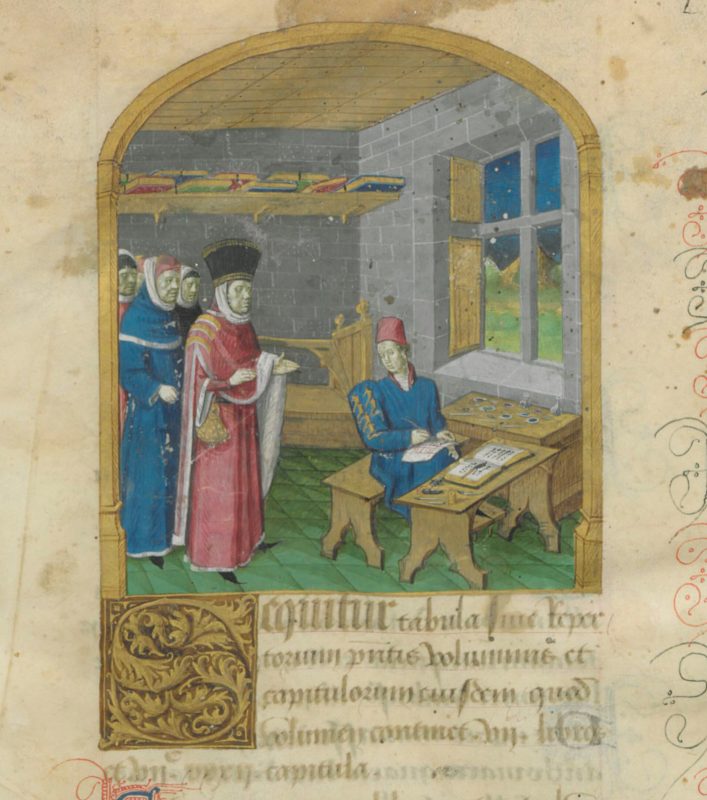

One of the rare illustrations of an illuminator at work can be found on the first folio of Mare historiarum ab orbe condito (Cod. Latin 4915, fol. 1r, BnF, Paris) where a 15th century anonymous illuminator is shown in his atelier during a visit by one of his customers [Figure 3].[4] Quills, knife and the portable calamal (a pen-case attached to an closable ink well) are located on the table in front of him, while his painting implements are displayed on another table to his left side at the window. They comprise various shells with self-prepared watercolours, separate brushes for each colour, and two bottles. One bottle contains binding medium to temper the colours and the other probably water to clean brushes and dilute the colours. The working area is deliberately arranged in such a way that the light comes from the left side, facilitating shadow-free painting with the right hand.

Such images are of inestimable value, as they provide us insight into an illuminator’s working environment. These visual depictions are extremely scarce. For exploring the nature and preparation of black watercolours available to illuminators in Burgundy and elsewhere, another group of sources forms a useful body of indispensable references: illumination manuals and recipe compilations.

‘De arte illuminandi’: Instructions in the Craft of Illumination

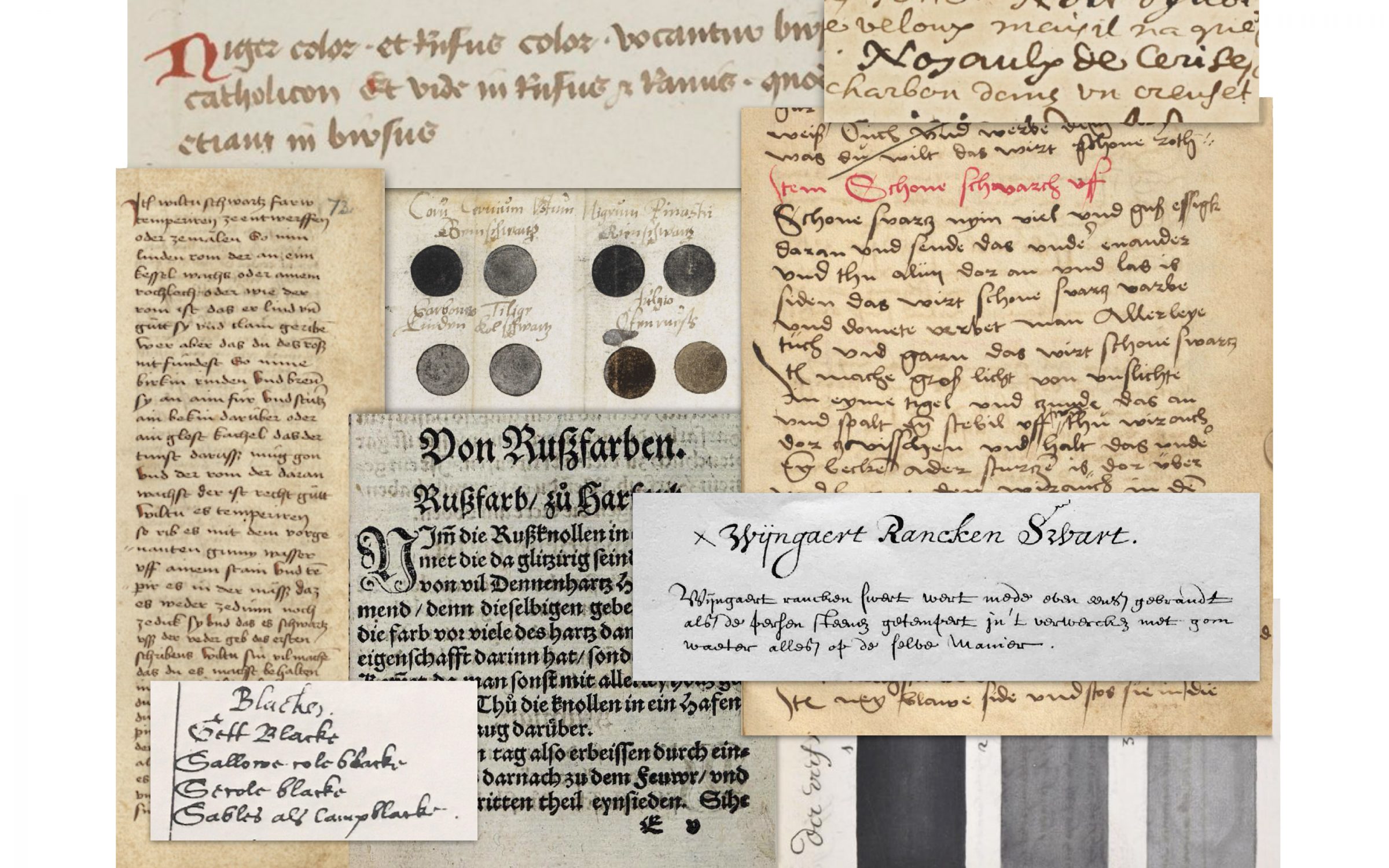

The time frame of interest for this study was initially restricted to textual sources of the period from c.1350-1500, but was expanded up to 1700, supported by the thought that successful workshop practices have proven to persist over time, and often over sustained long periods in pre-modern Europe, meaning that what was successful in 1500 might well have been in use in 1700. The lack of Burgundian sources was the reason to extend the selection not only over a longer period of time, but also to include sources of other European regions. The recipe compilation is comprised of historic sources in manuscript and print, written in Latin and European vernaculars, with the intentional exclusion of historical duplications [Figure 4].[5]

It might be argued that the introduction of the book in 1450 and the transition from parchment to paper meant such a deep revolutionary change that textual sources of a later period cannot be assumed to be of much help to understand illumination practices. Yet, this idea proves untenable, given that the preparation of watercolours — the medium of illuminators — did not dramatically change with the arrival of moveable type printing, for so long as paints and pigments were fabricated on a small scale in artists’ ateliers. While raw materials and the preparation of black watercolours remained mostly comparable over the centuries, related professions and the audience of dyeing manual changed considerably, as I discuss below.

Many sources from the late Middle Ages came down to us in miscellaneous manuscript compilations, testifying to a vivid monastic tradition in compiling, copying, and transmitting art technological know-how related to the production of illuminated manuscripts. An exception is the earliest of the chosen sources, De arte illuminandi,[6] probably written in southern Italy and dating from the end of the 14th century. Composed for teaching the illuminator’s craft, it is not a transcript of earlier treatises and no other copies of this text are known. Another important reference for 14th and 15th century illumination practices is the large corpus of Middle English recipe compilations which was recently discovered and rendered accessible thanks to the meticulous work of Mark Clarke.[7] These manuscripts provide a wealth of information and significantly enrich the archive, especially in the light of the relative scarcity of accessible continental European sources contemporary to Burgundian illumination.

Alongside the ongoing use of handwritten recipes, the sixteenth century saw a rise of print publications containing colour-making recipes for illuminators and painters, of which many were published in European vernaculars and often appeared in many editions and translations. Examples of such printed books include the Augsburger Kunstbuechlin, De secreti del reuerendo donno Alessio Piemontese, or Valentin Boltz von Ruffach’s widely known Illuminierbuch.[8] These manuals contain detailed descriptions of pigment production, the preparation of watercolours, and their application. Their publication aimed at a new audience, since the slow decline of the ancient art of illumination saw new professions emerging.

The direct successors of illuminators who continued the tradition of preparing their own watercolours and using parchment as painting support were the miniaturists; they painted miniature portraits and passed along the ancient techniques into the 19th century.[9] Evolving from the printing business, another profession emerged, the ‘hand-colourists’, who used watercolours to wash printed images and maps.[10],[11] The sixteenth century also saw the rise of professional ‘letter- or book painters’, commissioned to decorate and colour, for instance, the pages of the more and more popular alba amicorum with emblems, portraits, and other motifs emerging in the European context in aristocratic and learned circles.[12]

Apart from these professional books, the seventeenth century saw an increasing number of amateurs or virtuosi exploring the field of watercolour painting and sharing recipes. They relied on printed books and occasionally copied recipes by hand like Jacoba van Veen (b. 1635 – d. after 1687), who compiled parts of her text from sources such as Symon Andriessens Viervoudich Tractaet Boeck (Amsterdam, 1552) or Gerard ter Bruggens Verlichtery Kunst-Boeck (Amsterdam, 1616).[13] Due to this interest in watercolour, the circulation and publication of manuals, intended for this particular clientele, was wide spread, and they featured compelling titles like A Book of Drawing, Limning, Washing, or Colouring of Maps and Prints: […] Or, the Young-mans Time well Spent by the London publisher Thomas Jenner (London, 1652).[14]

Among the more than 100 pre-modern sources which were consulted for information on illumination and pigment making, a striking number of the 63 contained information on the nature or production of black pigments. Table 1 (downloadable here) presents an overview of all primary and secondary sources included in this study. In light of this rich corpus of black pigment recipes it seems remarkable that not one pre-1700 recipe for black watercolours written or published in Burgundian regions could be found, despite the highly advanced state of the art of illumination in Burgundy that attracts the attention of collectors, scholars, and museum curators alike. Nonetheless several indirect references to Burgundian colour recipes survived, related to regions that were under Burgundian-Habsburg reign. One example is the Montpellier copy of the Latin manuscript Liber diversarum arcium (about 1300, copied 1400 and 1450 in Italy) which comprises a compilation of recipes originating not only in the regions of modern-day Germany, France, and southern England, but also in Flanders.

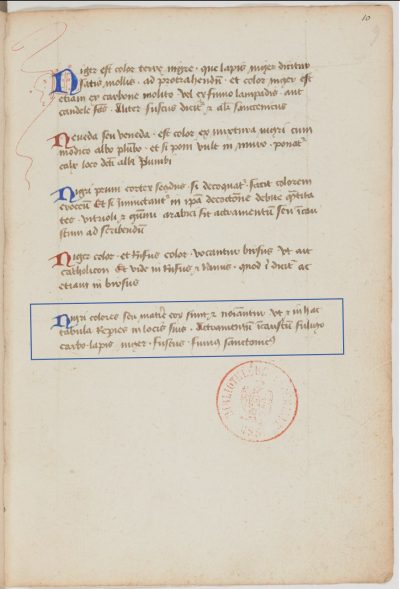

The famous compilation of manuscripts related to the art of painting by Jean le Bègue (1368 – 1457), a French lawyer and secretary to King Charles VI, also contains links to Burgundy even if not properly Burgundian. Compiled in 1431, its table of synonyms, which precedes the subsequent chapters, lists eight different black pigments under the lemma ‘Nigri colores’: ‘Actramentum, incaustum, fuligo, carbo, lapis niger, fuscus, fumus, sanctonicus‘[15] [Figure 5], and it specifies even more black pigments under corresponding lemmata. Among other chapters, Le Bègues’s manuscript includes several tracts assembled by Jehan Alcherius who travelled to Italy and France between 1382-1410. In his introduction Le Bègue notes that during his journeys Alcherius visited Jacob Cona, a Flemish artist living in Paris, who dictated to him De coloribus diversis modis tractator in sequentibus on 28 July 1398.[16] Alcherius’s interview with Cona primarily describes miniature painting, but unfortunately does not include any reference to the preparation and use of black pigments for illumination in the Burgundian Netherlands.

More informative are the recent investigations into sources documenting the acquisition and supply of painters’ materials at the Burgundian court by Susie Nash and Lorne Campbell. They provide a better understanding of the variety of artist materials available to artists, their origin, circulation, and price at the turn of the fourteenth century. While other pigments and gold leaf were frequently acquired, black pigments are listed only in one single entry of all of the accounts listed by Nash. And this purchase was definitely not destined for Burgundian illuminators, since it comprised of 6 cartloads, each of 17 sacks, containing charbon, or carbon black. These were sold by Perrenot Berbisey, on 14 June 1388, to be used by artists working at the church at Beaumetz. Each sack sold for 15 deniers, cheaper than vermillion (c. 160 denier/lb) or verdigris (60 denier/lb).[17] Another source discloses that by 1420, Collart Le Roy sold one and a half pound of Noire terre, black earth, for 12 deniers to Burgundian painters.[18]

As particular accounts of illuminators’ purchases are still to be found, sources that report on the availability of artists’ materials in general and their prices are of significant historical importance. Several authors compiled detailed overviews for specific regions and time frames.[19]

An Open-Access Digital Manual for Black Watercolouring

Scholars to date have assumed that the production of black pigments was rarely mentioned in medieval recipe collections.[20] In light of this conjecture, it was a surprise to discover that no less than 23 sources from the period between 1350-1500 contained remarks on black pigments for illumination. Another 40 premodern sources dating to a later period (1500-1700) prove that black colour knowledge continued to be written down, transmitted, and collected. Altogether, more than 250 entries on black pigments were found, which made it possible to differentiate the 50 black pigments. They are listed with the corresponding historic sources in Table 1 (downloadable here). Some sources only mention the name of a black pigment or colourant, others contain recipes for their preparation, or even include detailed instructions to manufacture black watercolours. The compiled 63 sources exhibit such an abundance and variety of raw materials used for black pigments that a systematization felt inevitable.

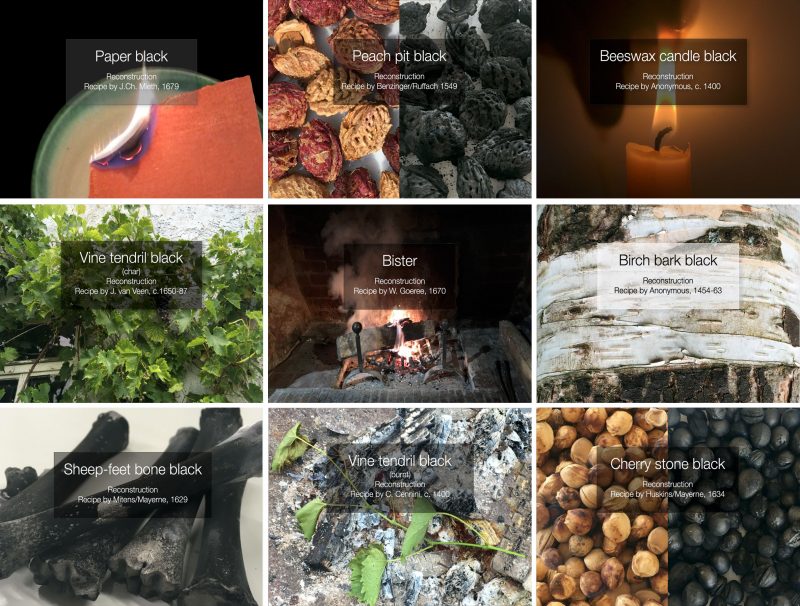

The richness of information on black pigments discovered in the historic sources was ultimately beyond the scale of a single essay. Consequently, I have much of the information as a supplement to this book, entitled ‘A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700’.[21] This ‘book-within-a-book’ describes the cultural-historical background of those 50 black pigments which were found in the textual sources for illuminators and limners. This supplement also includes historic recipes, and a discussion of historic preparation technologies. Step-by-step instructions for the reconstruction of black pigments using historic recipes can also be downloaded [Figure 6].

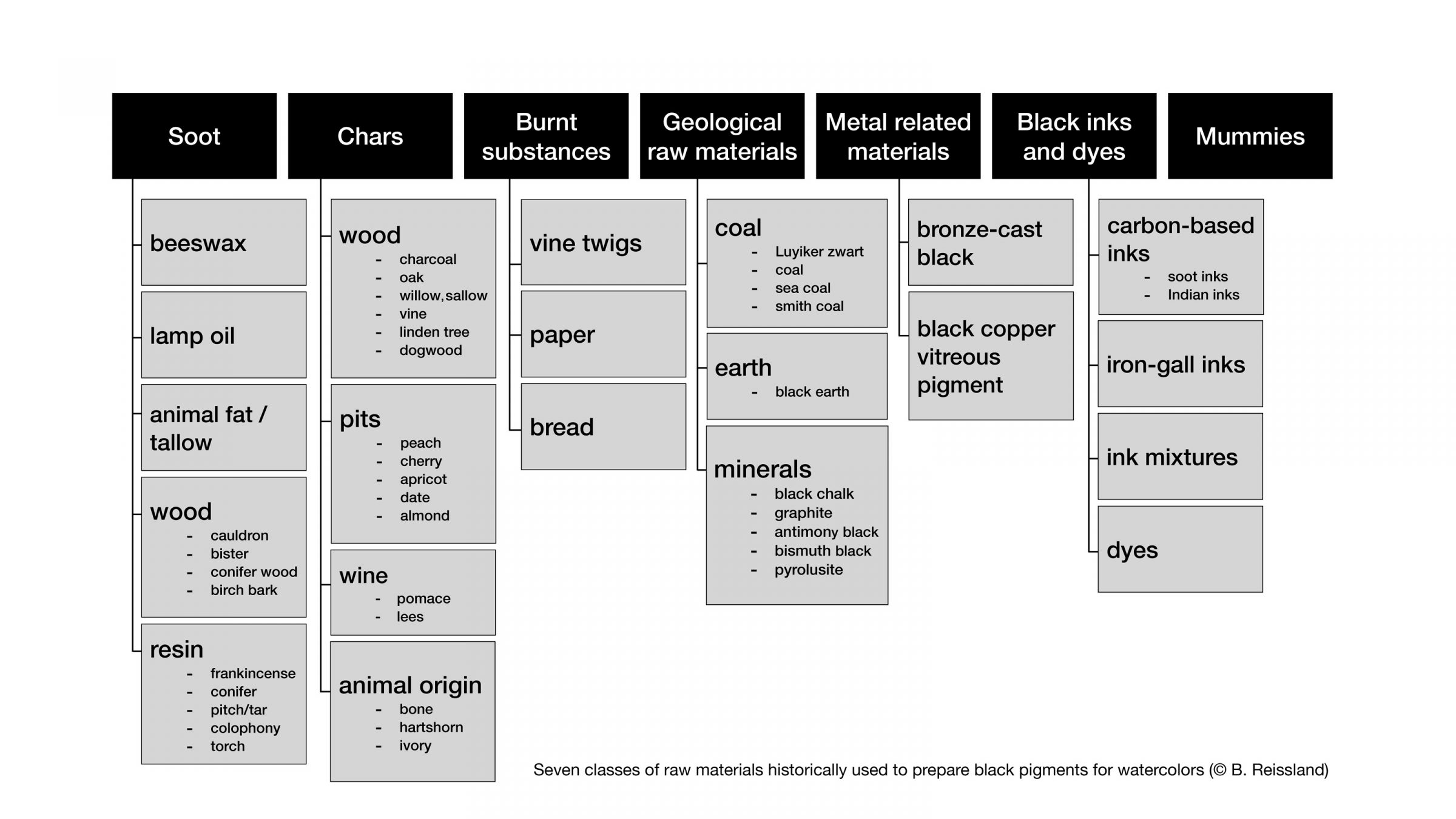

To present this extensive colour knowledge in a comprehensible way, the recipes were divided into seven black-pigment classes and sub-classes, ordered in reference to the raw materials used. The seven classes include (1) Soot, (2) Chars (3) Burnt substances, (4) Geological raw materials, (5) Metal-related black pigments, (6) Black inks and dyes and (7) Mummies [Figure 7] . The following paragraphs summarize the major results which are more clearly delineated in ‘A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700’.

Soot is the reaction product of incomplete burning of organic, carbonaceous materials. It is easy to produce and combustible raw materials such as fat and wood are readily available. When holding a smooth surface like a metal basin or a china plate above a flame, the burning process is interrupted and soot deposits onto the surface. It can easily be collected, which historically was done with a feather. Recipes mention the following five major sources of soot to produce black pigments: (1) beeswax candles which are mentioned in 14th and 15th century treatises when wax still was a luxury product [22], (2) different plant-based oils that were burnt in oil lamps, (3) tallow candles, (4) soot of wood, which initially meant deposits on cauldrons and on the walls of fireplaces (bister)[23], but later was produced on large scale for book-printing ink using resin-rich conifer wood after the invention of the book printing process [24], and (5) soot from burning resins (like frankincense, common pitch, or tar), and soot from torches, or ‘sable’. Soot pigments consist of extremely fine particles with a high coverage power. They do not mix easily with water and require sufficient dispersion, usually realized by thoroughly blending with a muller on a stone slab.

Chars play an important role as black pigments according to the consulted recipes. One of the oldest charred materials used as black paint is charcoal, or charred wood, which can be found in the ashes of wood-fuelled fires. Like soot, chars are a result of an incomplete burning process, which differs essentially from soot production. During charring, the materials to be processed are heated in nearly airtight containers, deliberately excluding oxygen and hindering combustion. At high temperatures in the absence of oxygen organic substances thermally decompose, meaning that chemical bonds break and non-carbon elements like hydrogen are released from the carbon chains to form gasses which then escape, contributing to a considerable loss of mass. The lack of oxygen prevents complete combustion and the remaining carbon structures cause a colour change to black. According to historic recipes, four major groups of charred materials can be distinguished: (1) charred wood, (2) shells, pits or nuts, like peach-, cherry- or apricot pits, (3) charred pomace or lees of wine, which were sold under the name Frankfurt black, the famous pigment for intaglio printing but also suitable for watercolours, and (4) animal-based chars from bones, horn or ivory, with ivory-black (ebur ustum) as the most renowned. Depending on the initial strength of the material, chars can be quite solid and may require pounding in a mortar and thorough grinding before they are suitable as pigments.

Burnt substances were another cheap and easily manufacturable source of black pigments. The difficulty with these processes is to stop the combustion process at the right moment, otherwise only grey-white ashes are left. Sources mention especially (1) burnt paper of gold-leaf booklets, (2) burnt bread (manchet), and (3) vine tendrils, an abundant by-product of pruning grapevines.

Geological raw materials were also useful sources of black pigment. The earth’s crust is rich in such sources, and a range of geological raw materials can be used, including (1) different sorts of coal, with coal of the area around Luik (Liège) potentially being of special interest to Burgundian illuminators,[25] (2) black chalks and dark brown earths like umbra or Cologne earth, and (3) minerals. The mineral Pyrolusite (manganese(IV)oxide, or MnO₂) even belongs to the most ancient black pigments used by mankind.[26] Stibnite, a naturally occurring black-grey coloured mineral is better known as antimony black (antimony (III) sulphide, or Sb₂S3 ). It was not mentioned in the consulted treatises, but was identified in at least two illuminations of different artists active around 1500.[27] Also Bismuth black was not included in artistic treatises but was present as granular elemental bismuth in eight illustrations by the French manuscript illuminator Jean Bourdichon (1457–1521), spread over three manuscripts dating from the early 1480s to 1515.[28] Graphite, recommended in 17th century recipes to obtain a crane colour, was not available to Burgundian illuminators, since it was discovered later, in the first half of the sixteenth century in Cumberland, England.

The compilation of recipes also referred to metal-related black pigments. Bronze-cast black (nero di terra di campana) is a side product of the ancient art of bell casting. It is mainly recorded in Italian treatises of the late sixteenth century, like those by Armenini and Borghini.[29] Earlier, and closer to the Burgundian period, some recipes refer to black copper vitreous pigment, which was used by painters of stained glass. Such a glass paint is already recorded in the fifteenth-century Montpellier Liber diversarum arcium.[30] Using these black pigments for illumination purposes suggests an exchange of material-related knowledge between different artisanal crafts, and are an example for the intensive exploitation of materials that seem disposable on the first sight.

As with the metal-related pigments, the use of black inks and dyes points to a lively sharing of knowledge between different professions. The use of ink in illumination is particularly understandable since scribes and illuminators cooperated closely. Taking a closer look at illuminations reveals that ink is quite a common part of miniatures. Inks were not only applied in diluted form as underdrawings, or aided the execution of fine details in miniatures, but were even present as drawings entirely executed in ink that served as independent illuminations.[31] Black coloured inks are usually based on soot; inks that appear brown are in most cases iron-gall inks.[32] Treatises often included recipes for writing ink in the section of watercolour recipes. Dyes like walnut shells, iron-gall dyes, iron-alder bark dyes, or logwood-based black dyes are usually mentioned in connection with ink making, and rest on a century-long tradition of black textile dyeing.[33]

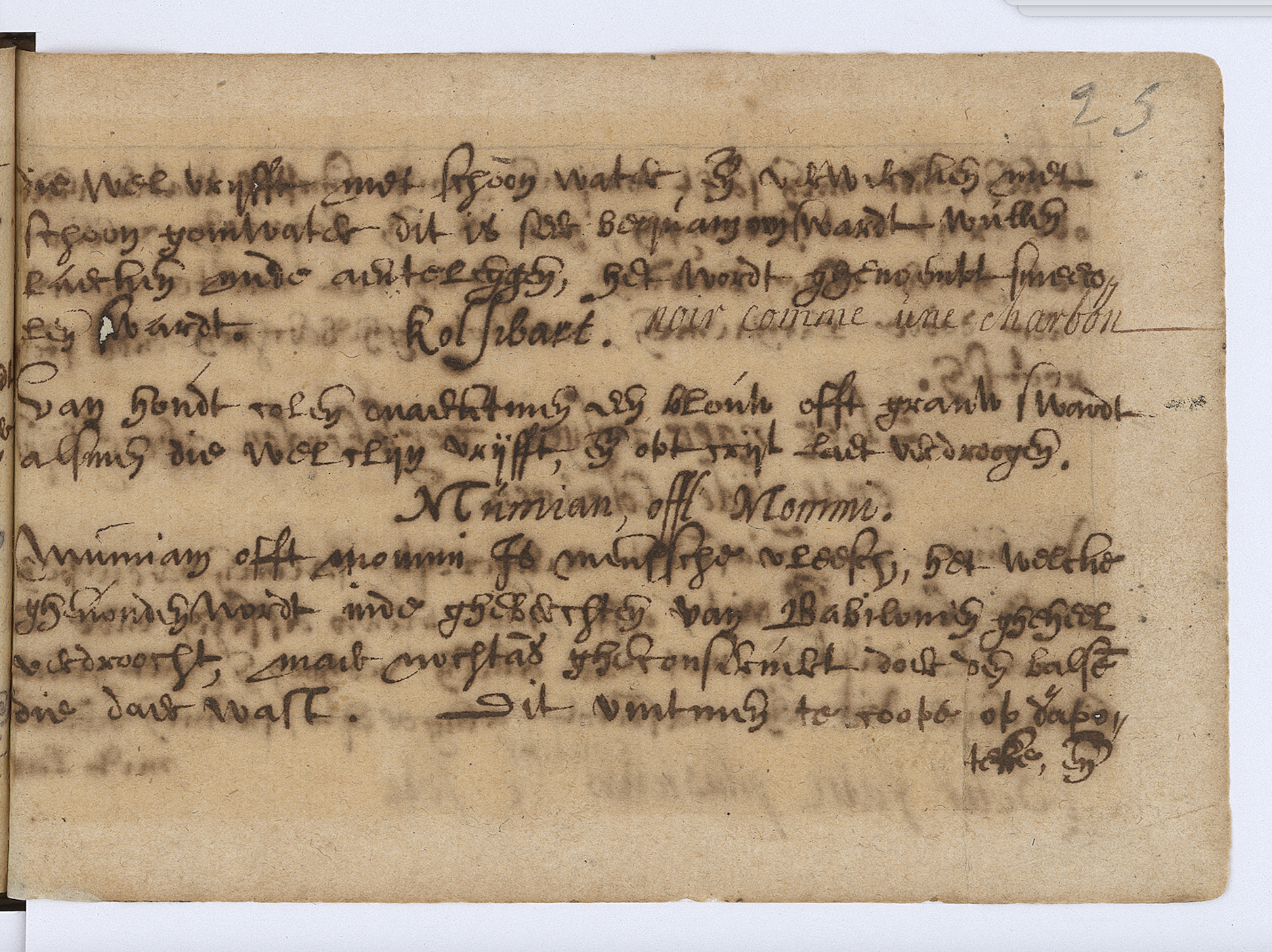

The last and seventh class refers to a sinister substance: pulverized mummy. Recommended by famous physicians like Guy de Chavillac (1300-1368), mummy was used in Europe as a cure for a variety of diseases during the fifteenth century. Probably before, but certainly in the middle of the sixteenth century, mummies or mummy parts could be purchased in pharmacies according to Valentin Boltz von Ruffach (b. before 1515 in Rufach – d. 1560 in Binzen), author of the famous Illuminierbuch: ‘Mummian. Mummian find man nienan / dann in den Apotecken / daß ist menschen fleisch kunstlich ußgedorret unn bereittet. Gibt auch fyne harfarb und kleidungen. Ist gar nützlich zu vylen dingen. Temperiers an mit einem dünnen gummi arabico wasser‘. [‘Mummian is nowhere to be found but in pharmacies. It is human meat artificially parched and prepared. It also makes fine hair color and clothes. Useful for many things. Grind it with a thin gum Arabic water’].[34] Regardless of its brown colour, mummy is often listed among black pigments in historical sources.[35]

The information compiled in ‘A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700’ on pre-modern black pigment production shows an overwhelming diversity of naturalia that were used as sources for black pigments. This suggests that a great variety of black tonalities could already be achieved by selecting different raw materials. The question arises if and how different binding media, additives or paint preparations can yield even more options when attempting to attain different shades and hues in black watercolouring. What do the treatises tell us about paint preparations with which illuminators could achieve specific effects? [Figure 8]

A comparative analysis of the historic sources has shown that instructions for the preparation of black watercolour paint in premodern recipes, manuals, and treatises are considerably consistent, with a clear preference for gum Arabic as binding medium [Table 2]. However, a chronological sorting of the sources shows an interesting trend. Authors of the 15th century continued to abide the tradition of earlier illuminators, who carefully chose a specific binding medium for each pigment and effect. However, the ancient binding media were gradually replaced by gum Arabic in the 16th century, a development that paralleled the decline of the profession of the illuminator. This development was completed in the 17th century, when egg yolk, egg white, and parchment glue played just a marginal role if at all in manuals for watercolour preparation. Moreover, it is noteworthy that added substances are scarcely recommended for the preparation of black watercolours. This suggests that illuminators achieved variations in hue and tonality primarily by carefully choosing their raw materials for black pigments rather than playing with the different qualities of additives or binding media.

“This black […] is suitable for painting black velvet”

Reworking a variety of black pigments for manuscript illumination with Birgit Reissland and Jenny Boulboullé, Atelier Building Amsterdam. A film by Katrien Vanagt and Stefano Bertacchini, 2020 ©Serafín Productions for ARTECHNE.

Surprisingly, about twenty pre-1700 sources comprise detailed information on the suitability of particular pigments to achieve specific painterly effects in black and point to techniques for painting diverse black fabrics, including velvets and satins. Many contain detailed instructions for rendering black hats, coats, stockings, shoes, armor and hair colour.[36] [Table 3]. For instance, an early recipe dates to around 1400 and advises to use bister as

‘a beautiful and fine hair color on whatever you apply it. . . . Apply it where you want or shade with it garment or stone mountains as it is good for many things to depict and for many things to shade’. [37]

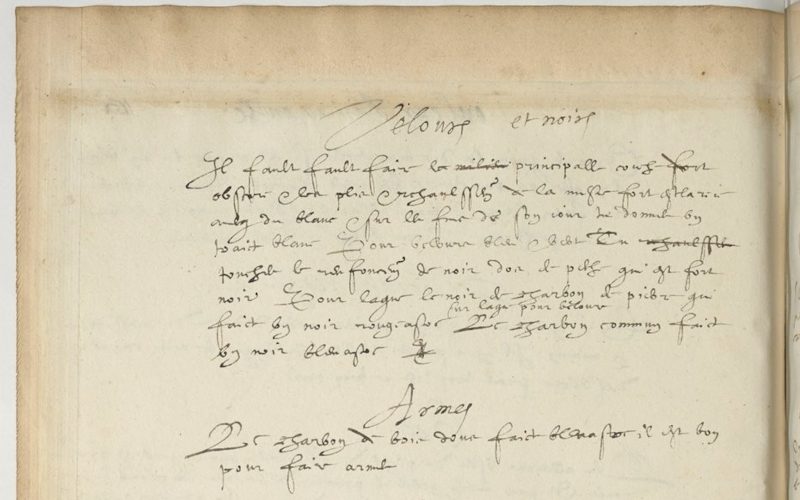

The importance of rendering a variety of black tonalities is also discussed in two recipes from an anonymous French manuscript, Bnf Ms. Fr. 640 [Figure 9], of the late 16th century, that has been studied closely by members of the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University : ‘Velvets and blacks. One needs [needs] to make thee / middle main layer very / dark, & its folds & highlights very bright with white, & on the edges of / its light, you make a white line. For blue & green velvets, you highlight touch the shading with peach pit black, which is very black. For lake, black of pit coal which makes a reddish black on lake for velvets. The common charcoal makes a whitish black’.[38]

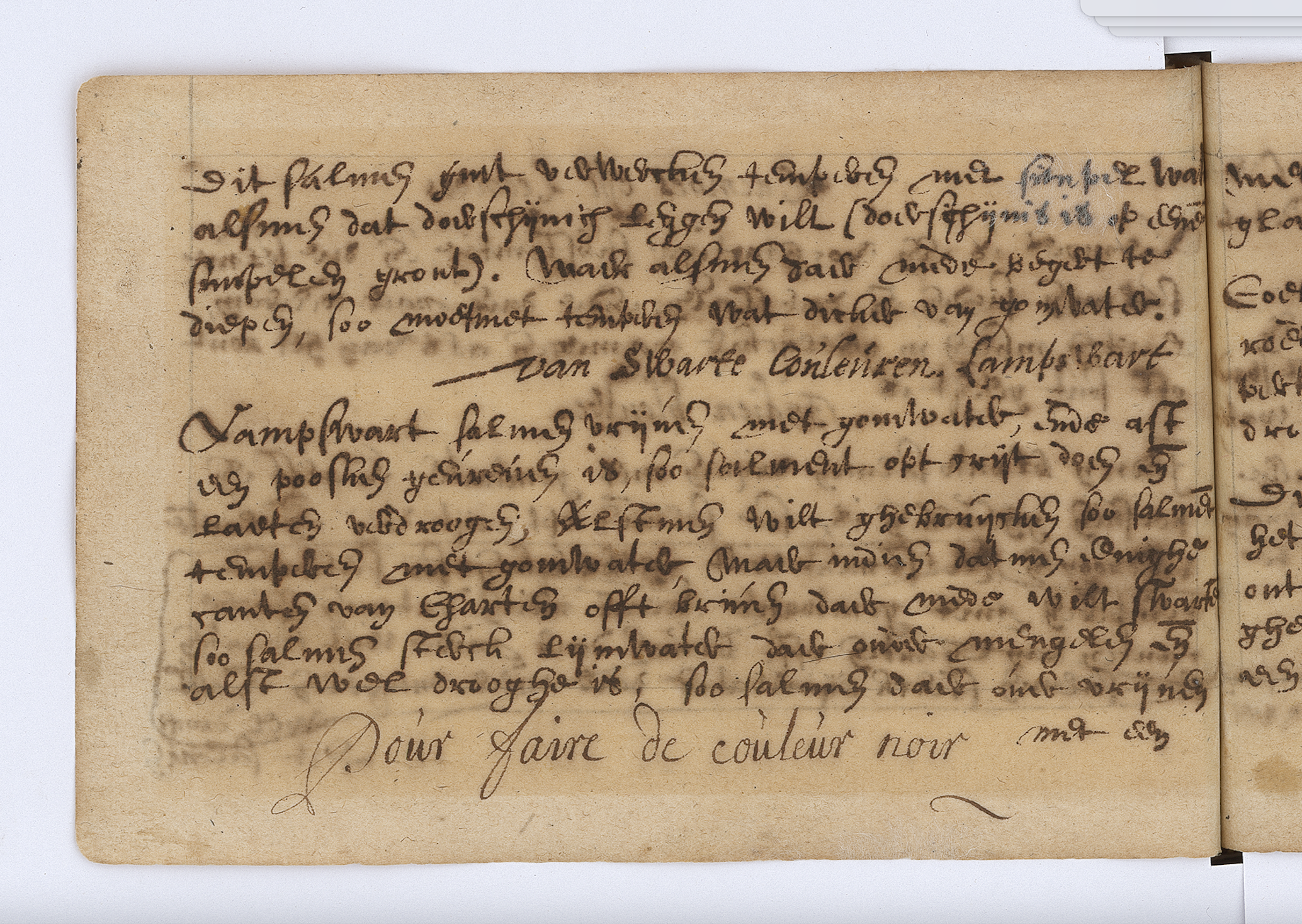

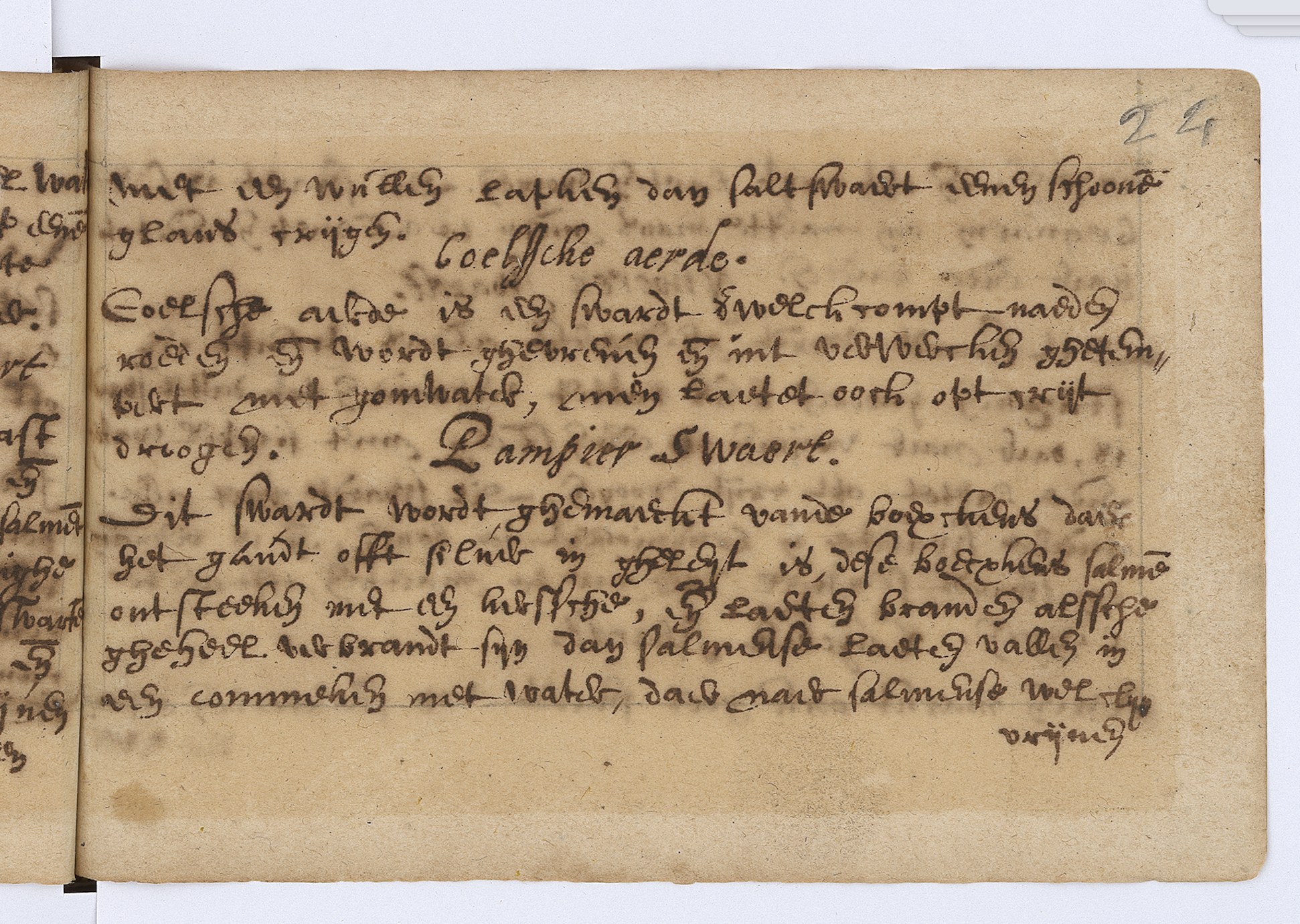

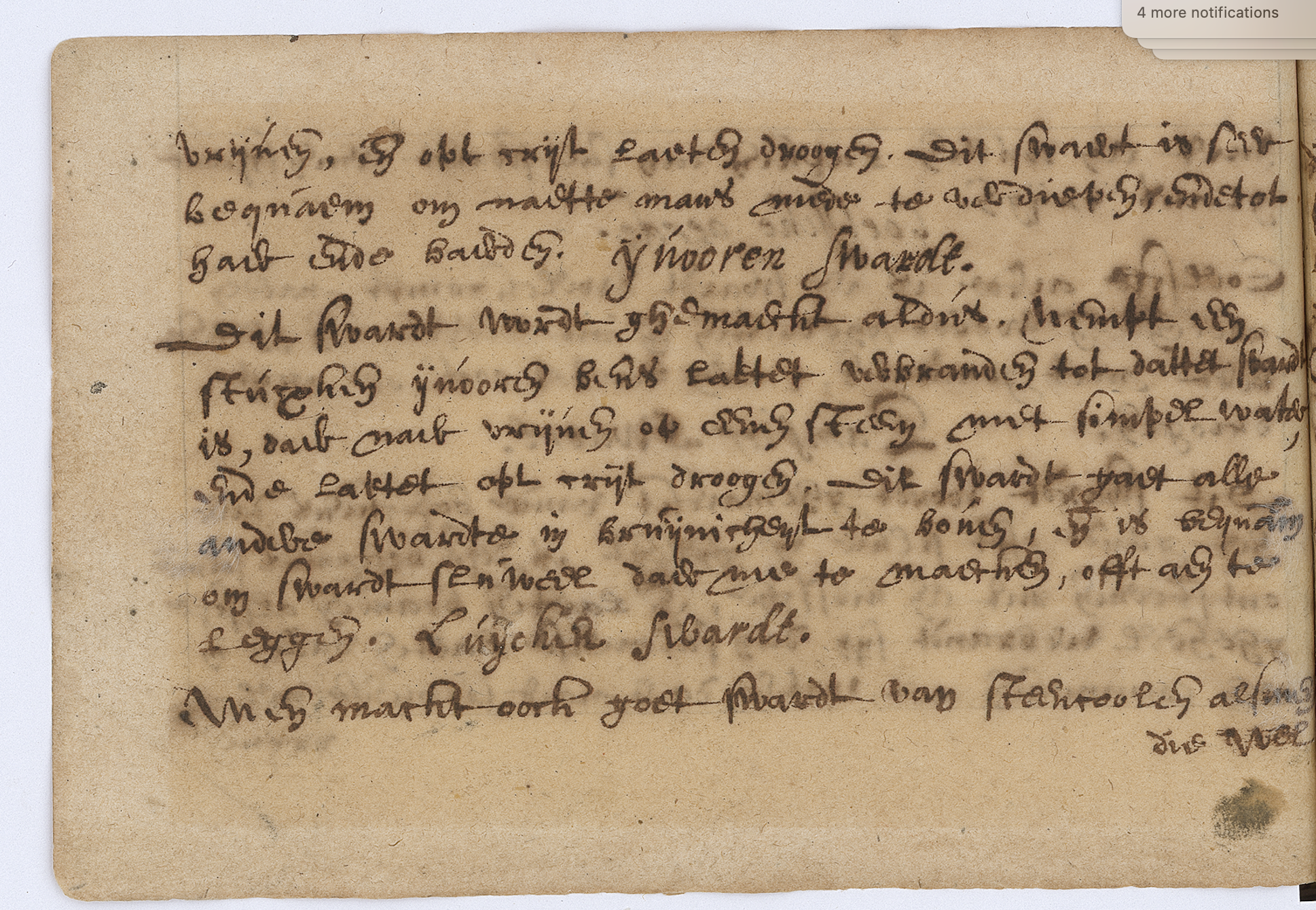

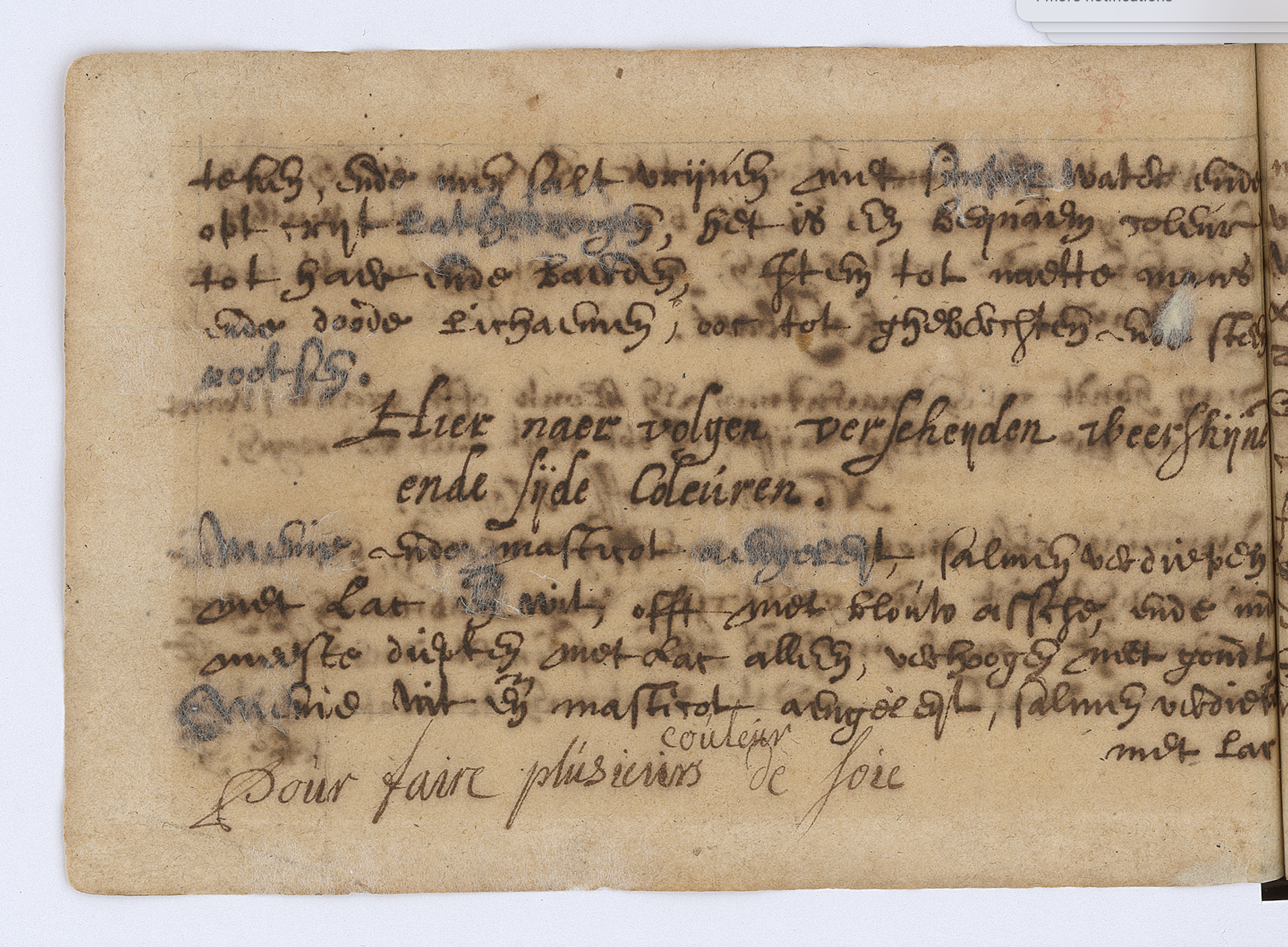

In terms of Burgundian recipes, the recipe from nearest to Burgundy is an early seventeenth-century small ‘manual’ in handy oblong format which survived in the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana in Rome (Ms. Lat. 7279).[39] The author of this manuscript remains unknown, but the recipes for illuminating are written in Middle Dutch, in a hand that points us to Antwerp, a city in Flanders that had become one of the most important production centers for illuminated manuscripts and prints.[40] The anonymous author might indeed build upon Burgundian traditions and reveals a deep insight into pigment qualities, a profitable knowledge in a harbour city with an abundant supply of artist materials from all over the world. Similar to other extant practical treatises it is structured by colour and contains a section entitled ‘Van swarte coleuren‘ (‘Of black colours’) which lists no less than seven black pigments for illuminating in watercolour on parchment or paper (fol. 23v-25v) [Figure 10].

Fig. 10. Seven black pigments for illumination used in Antwerp, late 16th, early 17th century. Anonymous. Dit is den boeck waer in veel schoone consten ende secreten staen aengaende die verlichterie, hoemen allen colueren wasschen ende bereidjen sal ende die selve ghebruijcken, Rome, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms. Vat.Lat 7279, fol. 23v-25v. Paper, 10×15 cm (oblong). https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.7

One of the entries (fol. 24v) mentions ivooren swardt (ivory black) as an unrivalled black pigment, suitable for rendering black velvets: ‘This black surpasses all the other blacks in brownness and is suitable for painting black velvet or to draft it’[41]; the recipe further recommends black coal pigment from Luyk for painting wullen laecken (fol. 24v, 25r), the famous finely woven wools manufactured in Flanders’ textile centers since the Middle Ages.[42]

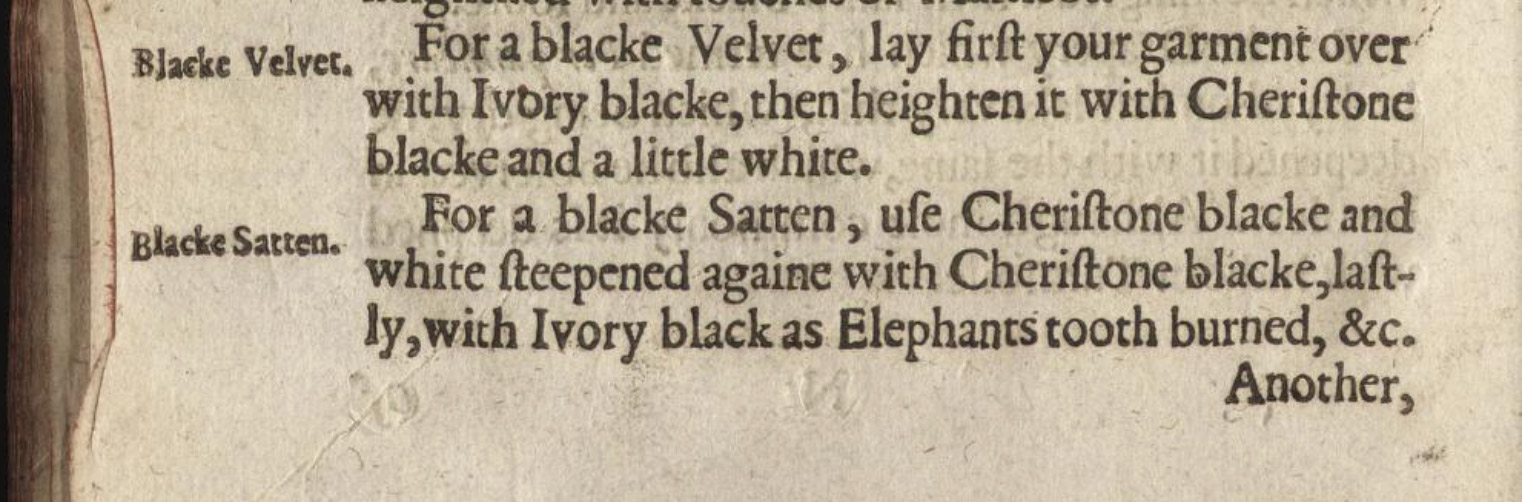

Rendering textile structures was usually not done with one pigment alone. Instead, they were often carefully layered. This could include the deliberate application of two black watercolours on top of each other, as in 1634 the English author and tutor Henry Peacham (1578 – about 1644) advises in The Gentlemans Exercise [Figure 11]: ‘Blacke Velvet. For a blacke Velvet, lay first your garment over with Ivory blacke, then heighten it with Cheristone blacke and a little white. / Blacke Satten: For a blacke Satten, use Cheristone blacke and white steepened againe with Cheristone blacke, lastly, with Ivory black as Elephants tooth burned, &c.’ [43] Also, mixing black with green or blue was an option according to Edward Norgate in 1631: ‘For Black velvett. Take lamp black and verdegreese for the first ground. When that is drye, take Ivory Blacke and verdegreese; shadow it with a little whyte lead mixed with Lamp Black’.[44] The combination of lamp black (‘Kienschwarz’), indigo, and lead white is advised for painting black monks’ habits and berets by Boltz von Ruffach in 1549: ‘Black colour for monch’s habits and berets. Take Kienschwarz [soot from conifer wood] / rub that with a little indigo and lead white. Temper everything well together. Shade with indigo with a little Paris red mixed with it. Highlight this with thin ash paint’.[45] As is evident from the cited sources, the tonality of shading and highlighting received special attention.

Systematic evaluation of historic recipes which instruct on the application of specific pigments for textile renderings also show some clear trends [Table 4] . Bister is recommended for hair and mustaches, as are burnt paper and mummy, most likely due to their brownish tone. Lamp black is advised for all sorts of headgear and garments. Cherrystone black and ivory black are used to depict black satin (cherrystone black under ivory black) and to render black velvet (cherrystone black on top of ivory black). According to the recipes, black from vine twigs is useful when depicting silk and satin garments, and burnt hartshorn is good for black velvets. Shadowing of skin was done with watercolour containing burnt paper or mummy. The latter seems to be a rather unintended coincidence: applying powdered human remnants to render complexion.

These recommendations are a crucial piece of information when attempting to identify black pigments with analytical techniques. They guide the scientist when formulating a first hypothesis about which pigments the illuminator might have applied, and this knowledge helps to determine the choice of analytical method. In addition, thorough knowledge of contemporary descriptions of pigments to render certain materials and textures will also inform the interpretation of analytical results.

Illuminating the Black Secrets of Burgundian Miniatures

The investigation of the famous frontispiece miniature of the first volume of the Chroniques de Hainaut, carried out during a conservation project in 1999, and a further examination in 2012, provided a promising case to learn more about the working procedures of Burgundian illuminators with respect to the depiction of the ducal court fashion.[46] Despite the diversity of black pigments that were available to illuminators at that time, along with the knowledge on careful layering and the combination of pigments to express certain effects, as well as the illuminator’s outstanding mastery in depicting different fabrics like Philip’s black burlet chaperon, his legwear and shoes [see Figure 1], the results of the scientific investigation are conspicuously wanting in detail. The analytic reports identify the black pigment used in the burlet chaperon and the gown as ‘carbon-based’, and state that no osseous material is present. The latter statement is usually based on the absence of the element phosphor, which indicates that no animal-derived pigments, such as bone or ivory black, were used.

Carbon-based is ultimately an unsatisfactory specification, as it is a generic term that can delineate any burnt substance of organic origin. It thus tells us nothing about the rich and diverse world of black colour knowledge that emerged from our reading of premodern recipe literature. That ‘carbon based’ has remained so far the standard answer provided for many a scientific analysis of black paint in medieval manuscripts, painfully illustrates the limits of recent analytical methods for the identification and characterization of black pigments available to pre-modern illuminators. Surely these limitations must be seen in light of the manifold requirements on analytical equipment that investigating these precious artworks imposes, such as a preferred examination in situ, and the application of micro- or non-destructive techniques. Until recently, only a few techniques met these requirements, limiting the identification to mainly inorganic components of paint applications. The situation improved recently, more than a decade after the examination of the Chroniques de Hainaut, when high-resolution in-situ imaging, micro-destructive surface sampling, highly sensitive analytical methods for characterization of organic components, and in-situ applicable spectroscopic techniques became available.[47] The present essay, together with the information compiled in the digital treatise and manual, ‘A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700’, aims to contribute to the development of new scientific techniques for the identification of black pigments in medieval illuminations, providing a profound understanding of potentially present black pigments, binding media, additives and paint layer structures.

Conclusion:

In light of the much-appraised artistic zenith which illumination reached in fifteenth-century Northern Europe, and the semantic significance of the colour black for the Burgundian period, it is intriguing that the art of black colouring mastered by pre-modern illuminators has largely remained a black box to both conservators and art historians.

Studying textual sources on black pigments was a surprise in many respects. It was surely unexpected to reveal such a rich palette of black watercolours, comprising about 50 different raw materials that were in the reach of Burgundian illuminators, including exotic commodities like frankincense; precious animal products, like ivory; gruesome human remains; and the blackened earth that was in direct contact with the bronze during bell founding.

The apparent mundanity of black colourants for illumination raises the question how Burgundian illuminators conveyed the richness of black fabrics on paper and parchment. Some of the black pigments at hand were indeed quite expensive and therefore suitable to represent the prosperity displayed in the splendid editions of the commissioned manuscripts, while cheap blacks like soot were omnipresent in every kitchen, adhering to fireplace walls, or remaining as charcoal in extinct fires.

Puzzled by the mastery of Burgundian illuminators when they rendered black shades and textures, and triggered by the lack of any Burgundian recipes for black watercolours, my colleague Jenny Boulboullé and I were inspired to envision how a Burgundian manual could have looked like, a source to teach apprenticing illuminators the art of black colour making, a kind of Burgundian De arte illuminandi. This marked the birth of ‘A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700’. We reimagined it so to speak as the ‘lost’ source of the rich black colour knowledge that is apparent in the many depictions of a sumptuously dressed black prince, but that has never been written or has not survived the test of time.

Research of historic sources proved that the illuminator had indeed a broad assortment and an amazing choice to his disposal to fulfil the demanding task to create an everlasting image of their Duke dressed up in luscious black fashion. The illuminator’s choice certainly had also a political dimension in a society which was characterized by strategic image-building and carefully performed self-expression.

The lack of sound and illuminating analytical identification of applied pigments still leaves the question open which specific pigments Burgundian illuminators used when rendering the sumptuous black shades that textile artists were able to achieve at that time. It is now the challenge to the field of science to develop novel analytical techniques that allow us to overcome the tedious standard answer of ‘carbon-based black’.

Once the knowledge conveyed by the historic sources can be supported with sound analytical insights into the black palette of Burgundian artists, we will be able to add a new chapter to the gripping narrative of Burgundian illuminators, searching for the optimal black paint to adequately render the prosperity and magnificence of their black-dressed Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good.

Bibliography:

Andriessen, Symon. Viervoudich Tractaet Boeck. Inhoudende Vier Delen Ofte Tractaten, Soemen in Dye Naevolgende Tijtlien van Elck Tractaet Metten Registeren van Dien Claerlijcken Sien Ende Aenschouwen Mach. Nu Eensdeels Wten Nieuwen Vergadert. Campen: Steven Joessen, 1552.

Anonymous. Dit Is Den Boeck Waer in Veel Schoone Consten Ende Secreten Staen Aengaende Die Verlichterie, Hoemen Allen Colueren Wasschen Ende Bereijden Sal Ende Die Selve Ghebruijcken. Rome, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms. Lat. 7279,” 1600 – 1650. https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.7279.

—–. Kölner Musterbuch. Köln, Hist. Archiv der Stadt, Best. 7010 (W) 293 Handschriften (Wallraf), 1490.https://historischesarchivkoeln.de/MetsViewer/?fileName=http%3A//historischesarchivkoeln.de%3A8080/actaproweb/mets%3Fid=6B1BAA39-991F-45E8-BC77-3065D06E7702_000208844_Orig_n_kons1_20170627110531.xml.

—–. Montpellier Liber diversarum arcium. Montpellier, Bibliothèque interuniversitaire, section médecine, MS H 277, fonds ancient, 14th century. Digitized copies of some folios available at https://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/sommaire/sommaire.php?reproductionId=8067

—–. Recueil de Recettes et Secrets Concernant l’art Du Mouleur, de l’artificier et Du Peintre. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF), Ms. fr. 640, fol. 63v, sixteenth century (after 1579). Paper, 35cm (h). https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10500001g

—–. The Excellency of the Pen and Pencil, Exemplifying the Uses of Them in the Most Exquisite and Mysterious Arts of Drawing, Etching, Engraving, Limning […]. London: Thomas Ratcliff and Thomas Daniel, 1668.https://archive.org/details/excellencyofpenp00ratc.

Armenini, Giovanni Battista. De’ veri precetti della pittvra, libri tre: Ne’ quali con bell’ordine d’vtili, & buoni auertimenti […].Ravenna: Apresso Francesco Tebaldini, ad instantia di Tomaso Pasini Libraro in Bologna, 1587. https://archive.org/details/deveriprecettide00arme.

Bartl, Anna, Christoph Krekel, Doris Oltrogge, and Manfred Lautenschlager. Der “Liber illuministarum” aus Kloster Tegernsee: Edition, Übersetzung und Kommentar der kunsttechnologischen Rezepte. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2005.

Bate, John. The Mysteryes of Nature and Art : Conteined in Foure Severall Tretises, the First of Water Workes, the Second of Fyer Workes, the Third of Drawing, Colouring, Painting, and Engrauing, the Fourth of Divers Experiments, as Wel Serviceable as Delightful. 1st ed. London: For Ralph Mab and are to be sold by Iohn Iackson and Francis Church at the Kings armes in Cheapeside, 1634. https://archive.org/details/mysteryesofnatur00bate.

Boltz von Ruffach, Valentin. Illuminier Buoch, wie man allerley farben bereitten, mischen, schattieren unnd ufftragen soll : Allen jungen angehnden Molern unnd Illuministen, nutzlich und fürderlich : Mit flysz und arbeit ersuocht, geuebt und zuosammen bracht. Basel: Jacob Kündig, 1549. https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-5578.

Borghini, Raffaello. Il Riposo Di Raffaello Borghini, in Cvi Della Pittvra, e Della Scultura Si Fauella, de’ Piu Illustri Pittori, e Scultori, e Delle Piu Famose Opere Loro Si Fa Mentione; e Le Cose Principali Appartenenti à Dette Arti s’insegnano : Borghini, Raffaello, 16th Cent : Florence: Marescotti Giorgio, 1584. https://archive.org/details/riposodiraffaell00borg/page/n4/mode/2up.

Braekman. Antwerpse ‘Consten Ende Secreten’ Voor Verlichters En ‘Afsetters’ van Gedrukte Prenten,” Verslagen en mededelingen van de Koninklijke Academie voor Nederlandse taal- en letterkunde (nieuwe reeks), 1994. https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_ver016199401_01/_ver016199401_01_0005.php#079.

Brafman, David. “Diary of an Obscure German Artist with (Almost) No Friends”, Getty Research Journal 6 (2014): 151–62. https://www.academia.edu/6544643/Diary_of_an_Obscure_German_Artist_with_Almost_No_Friends.

Bruggen, Gerard ter. Verlichtery kunst-boeck in de welcke de rechte fondamenten, ende het volcoomen ghebruyck der illuminatie met alle hare eyghenschappen klaerlijcken werden voor oogen ghestelt. 1st ed. Amsterdam: Koster, 1616. https://www.let.leidenuniv.nl/Dutch/Renaissance/Facsimiles/TerBrugghenVerlichtery1616/index.htm.

Brunello, Franco. De Arte Illuminandi : E Altri Trattati Sulla Tecnica Della Miniatura Medievale. Venice: Neri Pozza, 1992. https://www.worldcat.org/title/de-arte-illuminandi-e-altri-trattati-sulla-tecnica-della-miniatura-medievale/oclc/236060322?referer=di&ht=edition.

Buck, Stephanie. “On Relationships between Netherlandish Drawing and Manuscript Illumination in the Fifteenth Century.” In Flemish Manuscript Painting in Context: Recent Research, edited by Elizabeth Morrison and Thomas Kren, Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust, 2006. 103–116.

Burmester, Andreas, Ursula Haller, and Christoph Krekel. “Pigmenta et Colores: The Artist’s Palette in Pharmacy Price Lists from Liegnitz (Silesia).” In Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, Eds.: Jo Kirby, Susie Nash, Joanna Cannon. London: Archetype Publications, 2010. 314-324.

Cambridge illuminations research project, Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge, https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/research/cambridgeilluminations

Campbell, Lorne. “Suppliers of Artists’ Materials to the Burgundian Court.” In Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, Eds.: Jo Kirby, Susie Nash, Joanna Cannon, London: Archetype Publications Ltd, 2010. 183–185.

Clarke, Mark. The Medieval Painter’s Materials and Techniques: The Montpellier Liber Diversarum Arcium. London: Archetype Books, 2011.

Clarke, Mark. The Crafte of Lymmyng and the Maner of Steynyng: Middle English Recipes for Painters, Stainers, Scribes, and Illuminators. Oxford: Oxford university press, 2016.

De Columma, Joanne. Mare Historiarum Ab Orbe Condito Ad Annum Christi 1250, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Cod. Latin 4915, c. mid fifteenth century https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000905v/f11.item.

De Guise, Jacques and Wauquelin, Jean (transl.). Chroniques de Hainaut, Vol. 1, Bibliothèque royale de Belgique (KBR), Ms. 9242, c. 1450. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113

Eastaugh, Nicholas, Valentine Walsh, Tracey Chaplin, and Ruth Siddall. Pigment Compendium. Elsevier, 2008.

Goedings, Truusje. “Afsetters En Meester-Afsetters” De Kunst van Het Kleuren 1480-1720. Uitgeverij Vantilt, 2015.

Hardie, Martin, and Edward Norgate. Miniatura; or, The Art of Limning. Oxford, Clarendon press, 1919. https://archive.org/details/cu31924016785572.

Heinzer, Felix. “Das Album Amicorum (1545-1569) Des Claude de Senarclens.” In Wolfgang Klose (Eds.): Stammbücher Des 16. Jahrhunderts., 95–124. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1989. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/29754771_Das_Album_amicorum_1545-1569_des_Claude_de_Senarclens.

Heydenreich, Gunnar. “The Leipzig Trade Fairs as a Market for Painters’ Materials in the Sixteenth Century.” In Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, Eds.: Jo Kirby, Susie Nash, Joanna Cannon, 297–313. London: Archetype Publications, 2010. 297-313.

Jenner, Thomas. A Book of Drawing, Limning, Washing, or Colouring of Maps and Prints: And the Art of Painting, with the Names and Mixtures of Colours Used by the Picture-Drawers. Or, the Young-Mans Time Well Spent. London: Simmons, 1652. https://www.shipbrook.net/jeff/bookshelf/details.html?bookid=13.

Kirby, Jo, Susan Nash, and Joanna Cannon, eds. Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700. London: Archetype Publikations, 2010.

Kirby, Jo. “Trade in Painters’ Materials in Sixteenth-Century London.” In Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, Eds.: Jo Kirby, Susie Nash, Joanna Cannon, 339–55. London: Archetype Publications Ltd, 2010.

Le Begue, Jean. Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF), Ms Latin 6741, 1431. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10525796f/f1.item

Leiden University Library, Collection guide Alba amicorum Collection (ubl290), https://digitalcollections.universiteitleiden.nl/view/item/1887225?solr_nav%5Bid%5D=0ab40476a96d4d613cbc&solr_nav%5Bpage%5D=28&solr_nav%5Boffset%5D=3

Nash, Susie. “‘Pour Couleurs et Autres Choses Prise de Lui’ The Supply, Acquisition, Cost and Employment of Painters’ Materials at the Burgundian Court, c. 1375-1419.” In Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, Eds.: Jo Kirby, Susie Nash, Joanna Cannon. London: Archetype Publications Ltd, 2010, 97-182.

Neven, Sylvie. The Strasbourg Manuscript: A Medieval Tradition of Artists’ Recipe Collections. London: Archetype Books, 2016, table 2, 30 “List of the manuscripts of the Strasbourg Tradition”.

Norgate, Edward. Miniatura or the Art of Limning. Edited transcript by Martin Hardie. Oxford: 1919, Clarendon Press, 1621. https://ia700402.us.archive.org/11/items/cu31924016785572/cu31924016785572.pdf

Ortega Saez, Natalia. Black Dyed Wool in North Western Europe, 1680-1850: The Relationship between Historical Recipes and the Current State of Preservation, PhD-thesis, University of Antwerp, 2018.

Panayotova, Stella and Ricciardi, Paola. “‘Masters’ Secrets’.” In COLOUR: The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts, Ed. Stella Panayotova, London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller / Brepols, 2016, 119–161. https://www.academia.edu/29535928/Masters_Secrets_in_COLOUR_The_Art_and_Science_of_Illuminated_Manuscripts_ed._S._Panayotova_London_and_Turnhout_Harvey_Miller_Brepols_2016_119-161?email_work_card=title.

Pastoureau, Michel. Black: The History of a Colour, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2008, 78-104.

Peacham, Henry. The Gentlemans Exercise, or, An Exquisite Practise […] with divers other most delightfull and pleasurable observations for all young gentlemen and others : as also serving for the Necessary Use and Generall Benefit of Diuers Trades-Men and Artificers.London : Printed [by J. Legat] for I.M[arriott]. and are to bee sold by Francis Constable at the signe of the crane, in Pauls Church-yard, 1634. https://archive.org/details/gri_33125008547412

Piemontese, Alexis. Die secreten vanden eerweerdighen heere Alexis Piemontois: Inhoudende seer excellente ende wel gheapprobeerde remedien, teghen veelderhande crancheden, wonden, ende andere accidenten. Met de maniere van te distilleren, perfumeren, confituren maken, te verwen, colueren, ende gieten. Translated by Girolamo Ruscelli. Antwerpen: Christoffel Plantijn, 1558.

Reissland and Ligterink eds., The Iron Gall Ink Website, https://irongallink.org

Royal Library of the Netherlands, digital collection https://www.kb.nl/themas/vriendenboeken

Schäffel, Klaus-Peter. De Arte Illuminandi – Ein Lehrbuch Über Die Kunst Der Buchmalerei von Einem Unbekannten Italienischen Autor Des 14. Jahrhunderts Auf Latein Verfaßt Und Aufbewahrt Als Handschrift Nr. XII.E.27 in Der Nationalbibliothek von Neapel. Basel, 2007. https://www.schäffel.ch/download/pdf/qu_de_arte_illuminandi.pdf.

Smith, Pamela et al. (eds.). Secrets of Craft and Nature in Renaissance France. A Digital Critical Edition and English Translation of BnF Ms. Fr. 640, New York, 2020. https://edition640.makingandknowing.org

Spear, Richard E. “A Century of Pigment Prices: Seventeenth Century Italy.” In Trade in Artists’ Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700, Edited by Jo Kirby, Susie Nash and Joanna Cannon, London: Archetype Publications Ltd, 2010, 275–293.

Trentelman, Karen, and Nancy Turner. “Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon.” Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 40, no. 5, 2009, 577–584. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrs.2186.

Van Buren, Anne. “New Evidence for Jean Wauquelin’s Activity in the Chroniques de Hainaut and for the Date of the Miniatures.” Scriptorium 26, no. 2 (1972): 249–268. https://doi.org/10.3406/scrip.1972.978.

Van Buren-Hagopian, Anne. “Dress and Costume.” In Les Chroniques de Hainaut. Ou Les Ambitions d’un Prince Bourguinon. Eds: Pierre Cockshaw, Christiane van Den Bergen-Pantens, Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers, 2000, 111-117.

Vaughan, Richard. Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1970.

Veen, Jacoba van. De Wetenschap En[de] Manieren Om Alderhande Couleuren van Saij of Saijetten Te Verwen Etc. Oock Om Te Leeren Het Fondament Der Verlichterij Konst, 1650-1687. https://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/vrouwenlexicon/lemmata/data/Veen.

Verougstraete, Helene and van Schoute, Roger. “Le frontispice des Chroniques de Hainaut: Examen en laboratoire,” in Christiane van den Bergen Patens, Chroniques de Hainaut, 151 and 154.

Vogels, Annelies. “Nemo Artifex Nascitur: Het Zeventiende-Eeuwse Receptenboek van Jacoba van Veen (1635-1687),” De Zeventiende Eeuw, 18, 2002, 99–114.

Watteeuw, Lieve, and Marina van Bos. “Chroniques de Hainaut: Observaties En Resultaten van de Analyses Op Zes Miniaturen.” In Les Chroniques de Hainaut. Ou Les Ambitions d’un Prince Bourguinon. Eds.: Pierre Cockshaw, Christiane van Den Bergen-Pantens, Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers, 2000, 157–166.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[1] Less probable, the miniature might also show Wauquelins scribe, Jacotin du Bois, while writing the first and second volume of the Chroniques, copying Wauquelins translation. In: Chroniques de Hainaut, vol. 1, Ms 9242, fol. 2r. https://uurl.kbr.be/1310113.

[20] Bartl et al., Der ‘Liber illuministarum’ aus Kloster Tegernsee, 547.

[21] See Reissland, 'A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700' elsewhere in this volume.

[21] See Reissland, 'A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700' elsewhere in this volume.

[21] See Reissland, 'A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700' elsewhere in this volume.

[21] See Reissland, 'A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700' elsewhere in this volume.

[21] See Reissland, 'A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700' elsewhere in this volume.

[21] See Reissland, 'A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700' elsewhere in this volume.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[28] Trentelman and Turner, 'Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Manuscript Illuminator Jean Bourdichon', 577–84.

[41] Anon., Dit is een Boecxke waer in veel schoone consten ende secreten staen aengaen die verlichterie hoemen allen colueren wasschen en bereyden zal ende die selve ghebruycken, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana Rom, Ms. Lat. 7279. https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.7279