‘A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700’ is an open access resource which stands in the tradition of the first printed dyers’ manuals that were advertised as works ‘for the public benefit’, revealing the art of colouring textiles to each and everyone who wished to learn or perfect their dyeing skills’.[1] While preparing my critical contribution to this collection, ‘Black Colour Technologies for Burgundian Dyers, 1350-1700’, my collaborator Jenny Boulboullé and I realized that the historical sources that I had consulted gave a truly surprising account of a varied abundance of raw materials used to prepare black watercolours. We learned about medieval bee-keepers, expensive frankincense that came all the way from the Arabian Peninsula and India, cheap soot scraped off the walls of kitchen hearths, and much more. In light of this surprising abundance, we felt that this information should be accessible to a wider audience and we decided to create a little book-within-a-book as an addendum to Burgundian Black. This born-digital manual shares the secrets of black illumination compiled from historic sources. We re-imagined it, so to speak, as a ‘lost’ source of the rich black colour knowledge of medieval illuminators, which has never been written down, or has not otherwise survived the ravages of time.

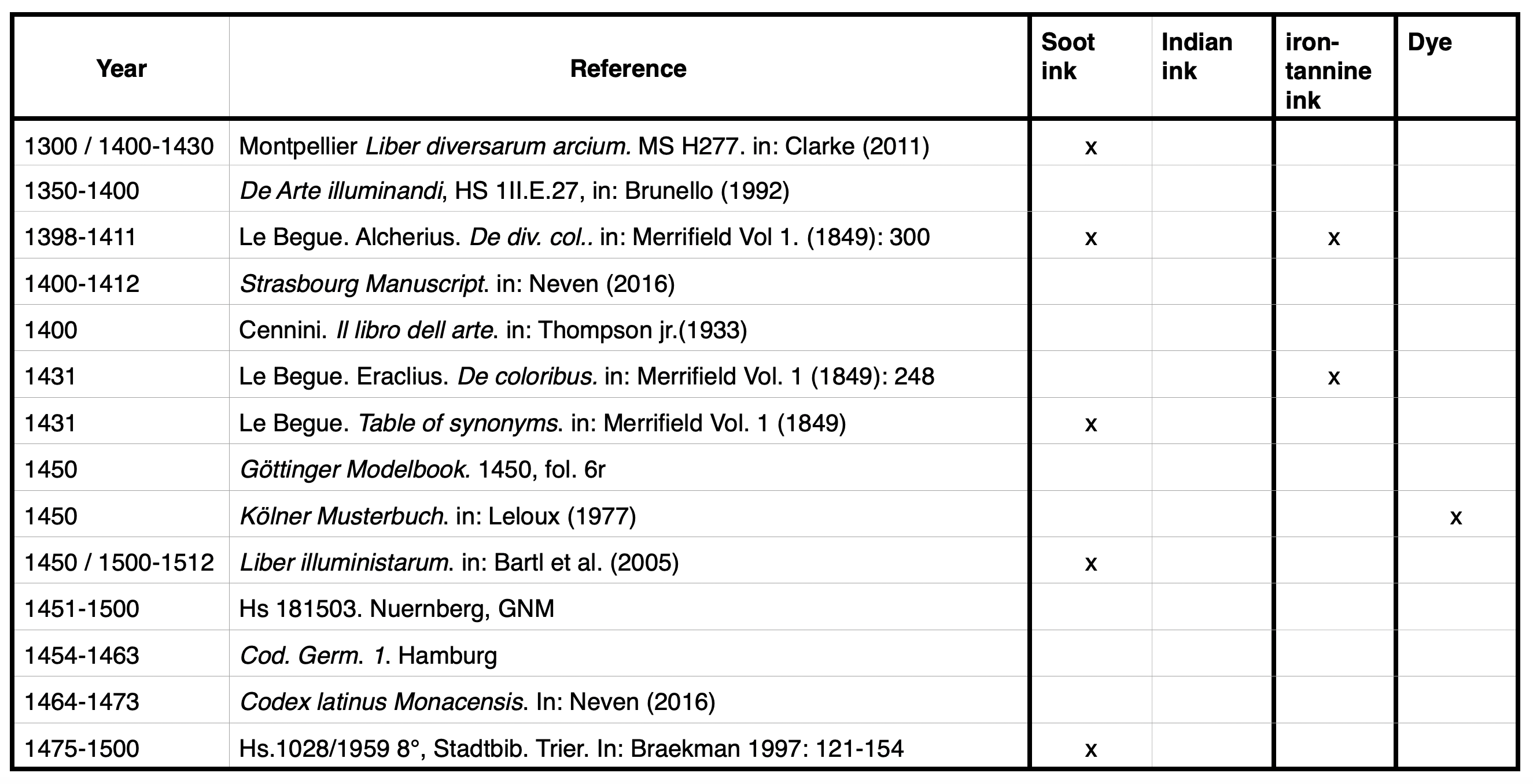

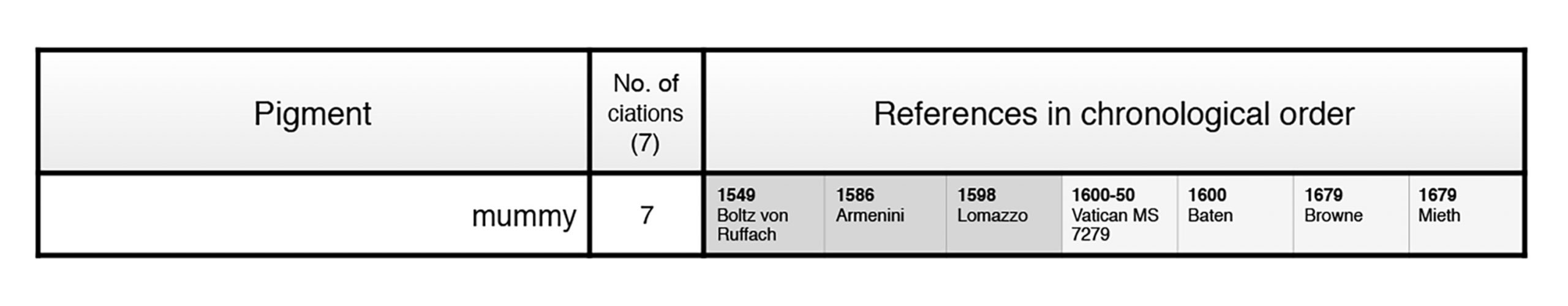

‘A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700’ is comprised of information I have found in historic treatises for black watercolouring, written by and for illuminators and limners, covering a period of 350 years (1350-1700). Remarkably, these sources revealed an unexpected number of 50 black pigments. To allow for a fast orientation, these pigments were sorted into seven classes. Claiming completeness is not the aim here, since the scope of this project is centered around Burgundy. While the pigments are the same for illuminators and for artists painting in tempera or oil, it might be worth mentioning that, historically, the preparation of pigments and the preparation of watercolour paint were two separate steps. This is different from the preparation of oil colours, where the pigment is ground and the paint is prepared at the same time. Traditional tools and technologies for the production of black watercolour paints are explained in order to provide a basis for practical experiments.

We carried out many reconstructions over the course of a year to better understand historic sources on black pigment technologies.[2],[3] The instructions are presented as short ‘how-to’ reconstruction manuals elsewhere in this volume, including references to the historic recipes and visual documentation of our reconstruction experiments and lessons learned. I am thankful to all the students and colleagues, especially those of the Universities of Antwerp and Amsterdam, who shared their knowledge and enthusiasm in order to bring medieval technologies to life again. Digital availability of sources was crucial for this study and it is a great and invaluable benefit that more and more institutes are willing to provide access to their digital repositories for scientific research. My friend and colleague Jenny Boulboullé is the initiator of ‘A Practical Guide to the Production of Black Pigments, 1350-1700’ for which I am deeply grateful. It is our desire to inspire anyone who wishes to learn the medieval way of preparing black watercolours.

We would like to thank the ARTECHNE project, led by Sven Dupré and funded by the European Research Council, the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands and the publishers of EMC imprint for making it possible to publish this open access resource.

For help negotiating the catalogue of substances and processes used to make black pigments and watercolours, use this hyperlinked tree. Note that some pigments listed below include extensive accounts of their modern reconstruction; for illustrated .pdf instructions, follow the “[Reconstruction]” links.

PART 1: The Making of Black Pigments

Class 1: Soot

1.1 Soot of Beeswax [Reconstruction]

1.2 Soot of Animal Fat/Tallow

1.3 Soot of Lamp Oil

1.4 Soot of Wood

1.4.1 Soot of Cauldrons

1.4.2 Soot of Fireplaces and Chimneys (Caligo, Fuligo, Bister) [Reconstruction]

1.4.3 Soot of Conifer Wood (Lampblack)

1.4.4 Soot of Birch Bark [Reconstruction]

1.5 Soot of Resins

1.5.1 Soot of Frankincense

1.5.2 Soot of Coniferous Resins (Noir de Paris)

1.5.3 Soot of Pitch/Tar

1.5.4 Soot of Pix Burgundica

1.5.5 Soot of Colophony

1.5.6 Soot of Torches

Class 2: Chars

2.1 Charred Wood / Charcoal

2.2 Charred Vine, Willow, and Basswood [Reconstruction]

2.3 Charred Pits and Shells

2.3.1 Charred Peach Pits [Reconstruction]

2.3.2 Charred Cherry, Apricot, and Date Pits [Reconstruction]

2.3.3 Charred Almond Shells

2.4 Charred Vine Lees and Pomace

2.5 Charred Pigments of Animal Origin

2.5.1 Charred Bone [Reconstruction]

2.5.2 Charred Hartshorn

2.5.3 Charred Ivory

Class 3: Burnt Substances

3.1 Burnt Vine Twigs [Reconstruction]

3.2 Burnt Paper [Reconstruction]

3.3 Burnt Bread (Manchet)

Class 4: Geological Raw Materials

4.1 Coal, Sea Coal, and Luyker Zwart

4.1.1 Smith Coal

4.2 Earth

4.2.1 Black Earth

4.3 Minerals

4.3.1 Black chalk

4.3.2 Graphite/Black Lead

4.3.3 Antimony Black (Kohl, Stibium, Sulfuratum Nigrum)

4.3.4 Bismuth Black

4.3.5 Pyrolusite

Class 5: Metal-Related Materials:

5.1 Bronze-Cast Black

5.2 Black Copper Vitreous Pigment

Class 6: Black Inks and Dyes

6.1 Carbon-Based Inks

6.1.1 Soot Inks

6.1.2 India Inks

6.3 Iron-Gall Inks

6.5 Dyes

PART 2: The Making of Black Watercolours Using Black Pigments

1. Preparation of the Pigments

2. Preparation of the Binding Medium

3. Additives

4. Tempering Colours: Preparation of the Watercolour Paint

5. ‘This Makes a Perfect and Fine Black’

*****

PART 1: The Making of Black Pigments

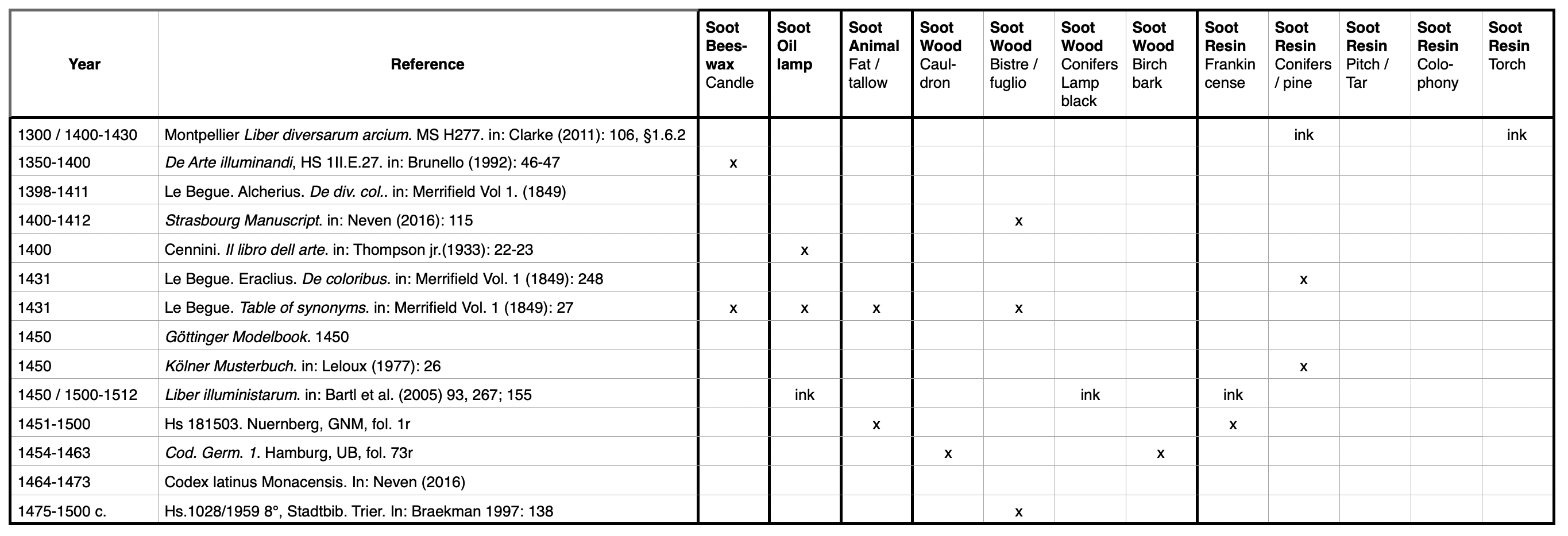

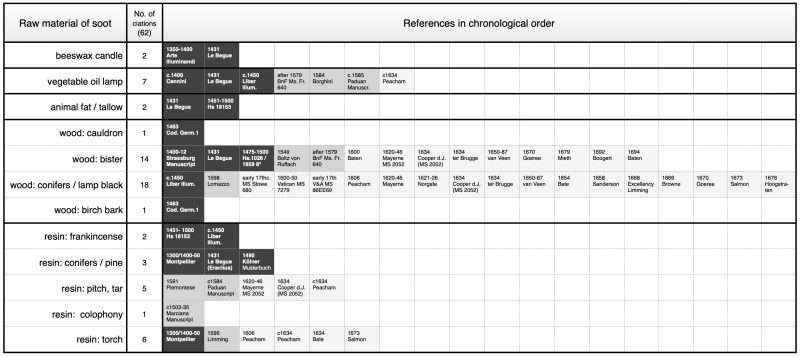

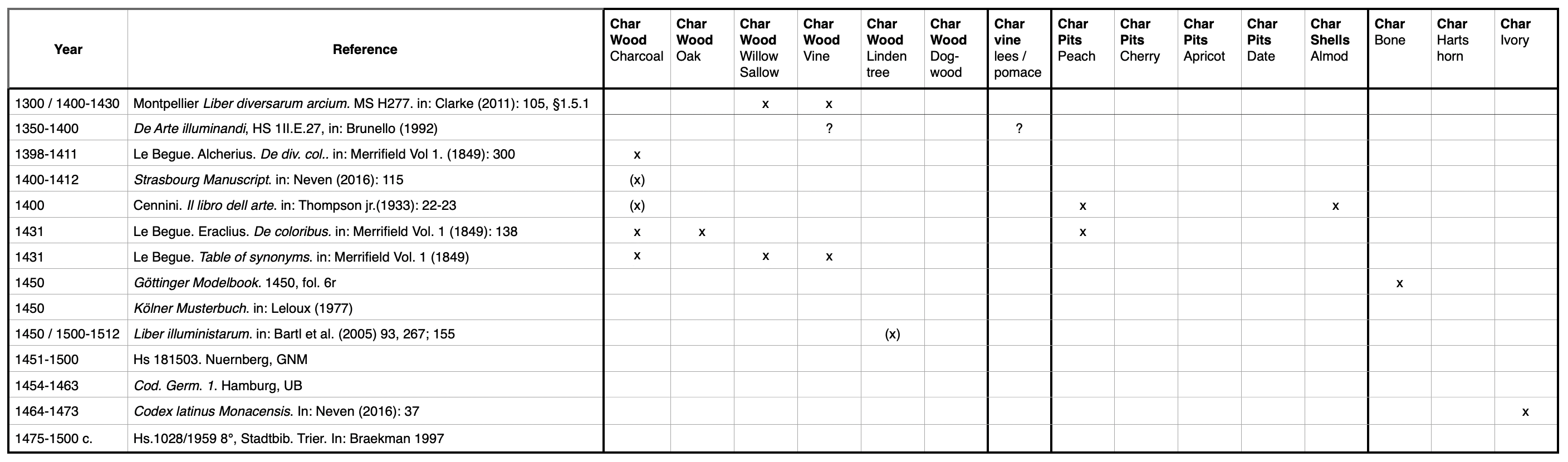

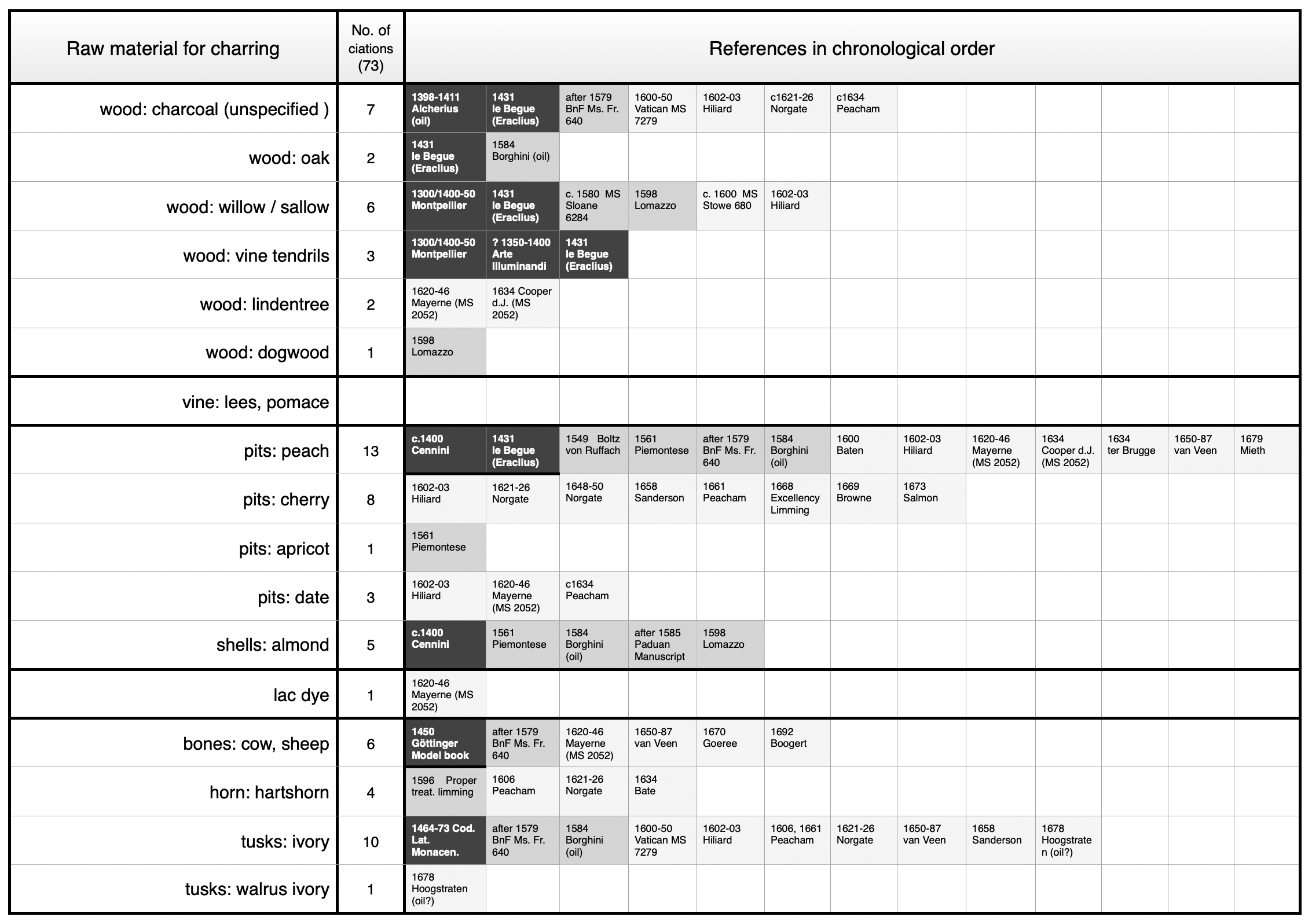

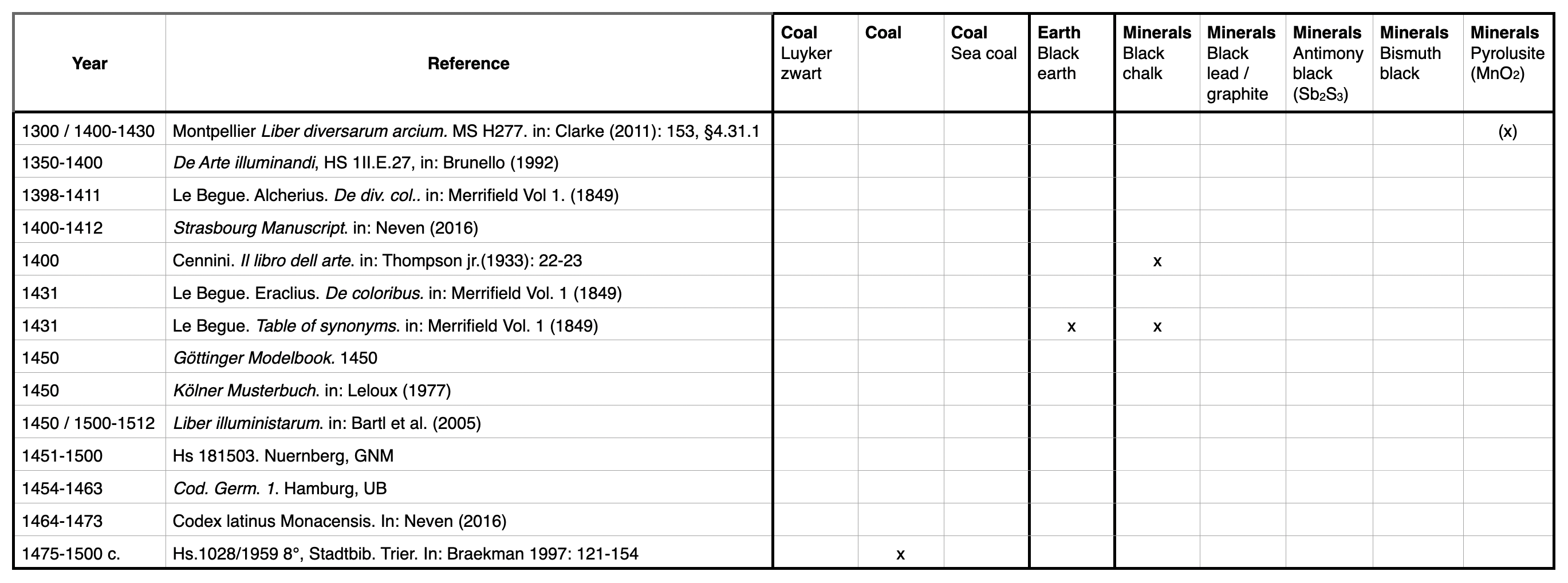

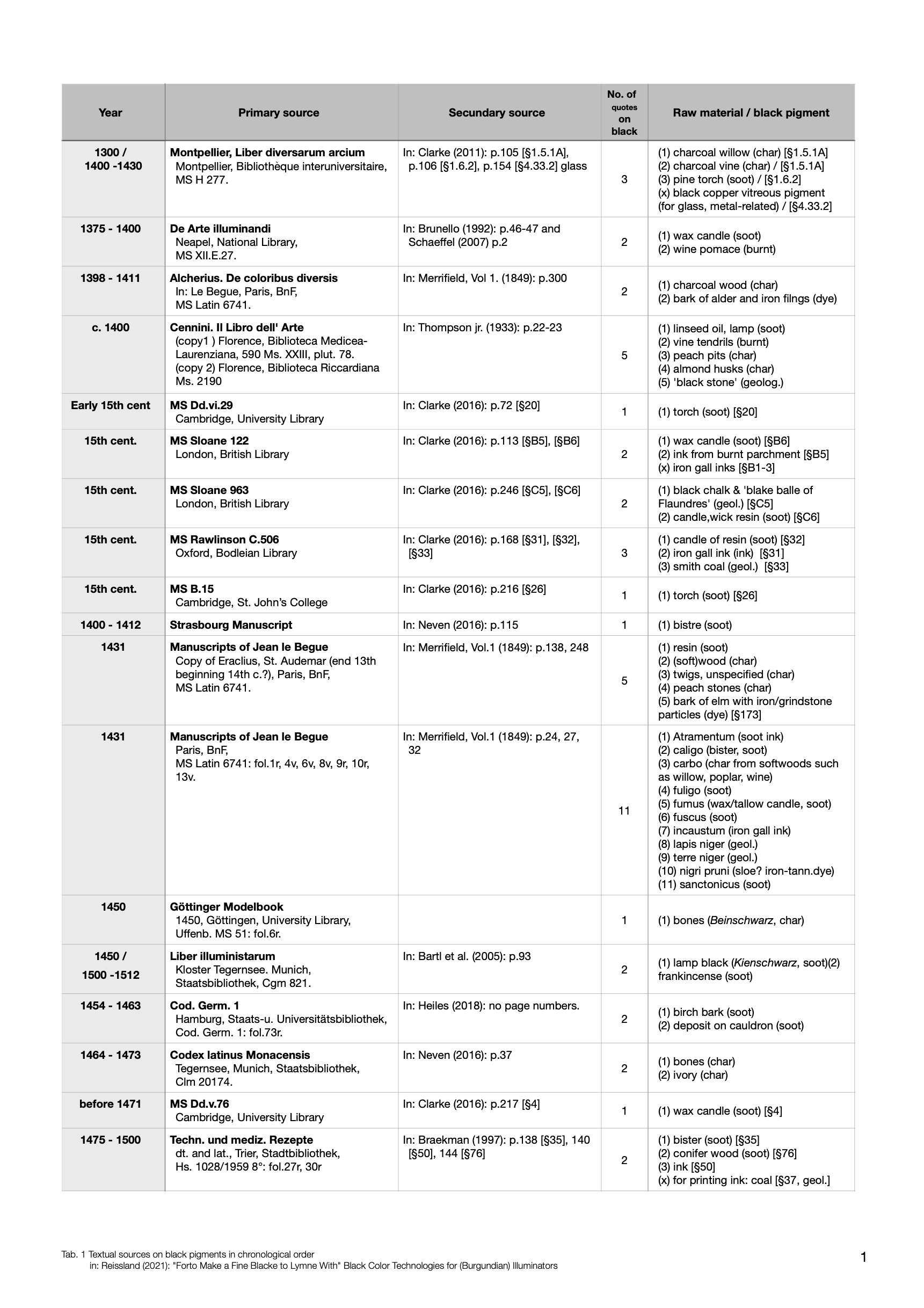

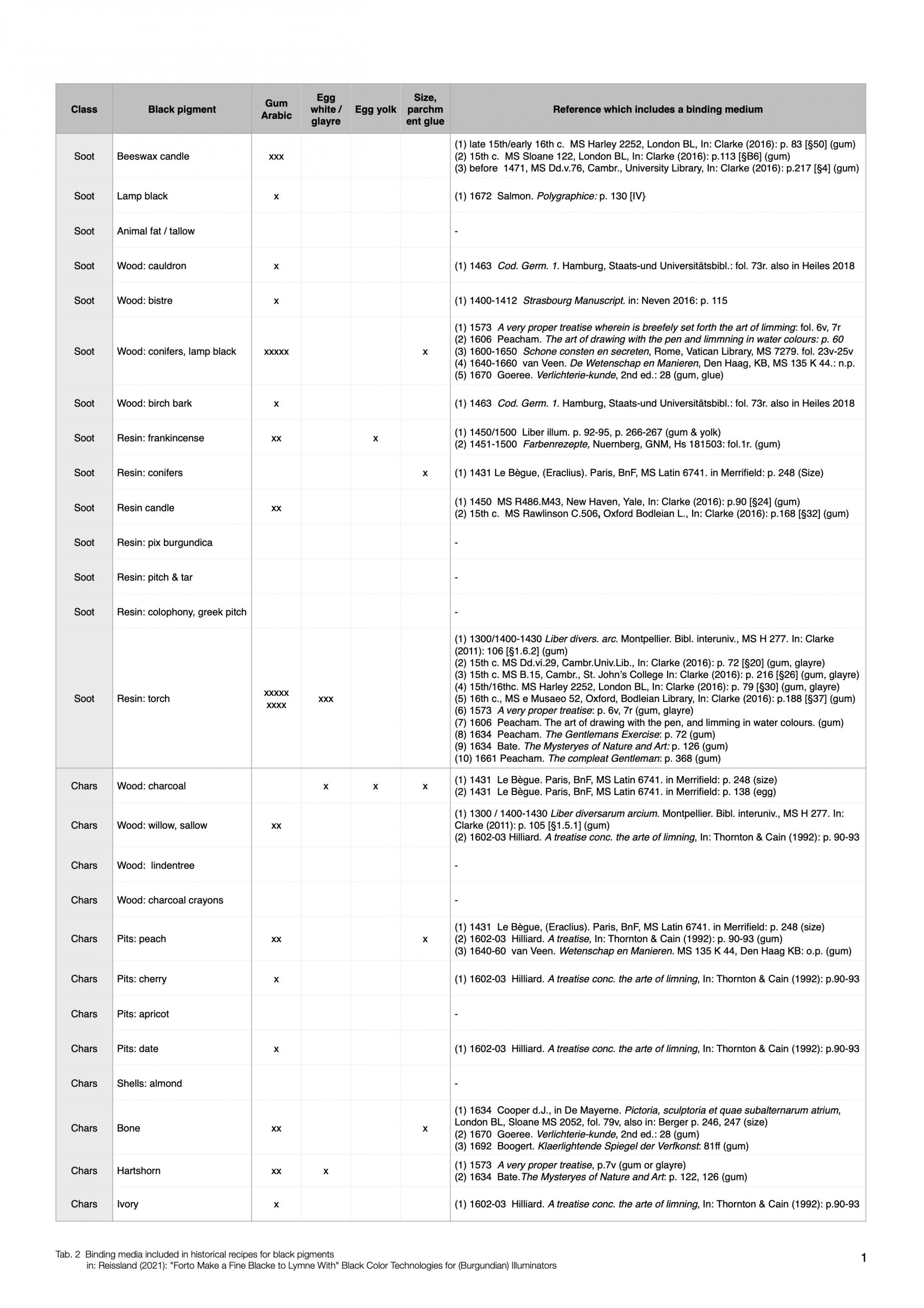

The surprising abundance of raw materials for black pigments found in 50 historic sources covering a period of about 350 years (1350-1700) required the establishment of a classification system. Based on the raw materials used, seven classes of black pigments for watercolours were identified. The classes are further divided in sub-classes [Figure 2].

The following seven sections each discuss one class of black pigments that was either mentioned in textual sources for illuminators and limners, or was identified on miniature illuminations. Each of the seven classes is first introduced by a general description of the preparation principle. This description is followed by an explanation of the origin of every raw material with a focus on the availability in regions under Burgundian-Habsburg reign. A source-based description of the preparation of the related black pigment is provided. At the end of each class, the corresponding historic sources are presented in chronological schemes to allow for quick orientation. If available, reconstructions of historic recipes are included as ‘how-to’ reconstruction manuals, containing ‘lessons learned’.

Class 1: Soots

Soot is the reaction product of the incomplete combustion of organic, carbonaceous materials. Many carbohydrates, such as wood or fat, burn easily, acting as fuel in the combustion process. The following five groups of raw materials comprise the major sources of soot in pigment production: (1) beeswax, (2) oil, (3) tallow, (4) wood, and (5) resins.

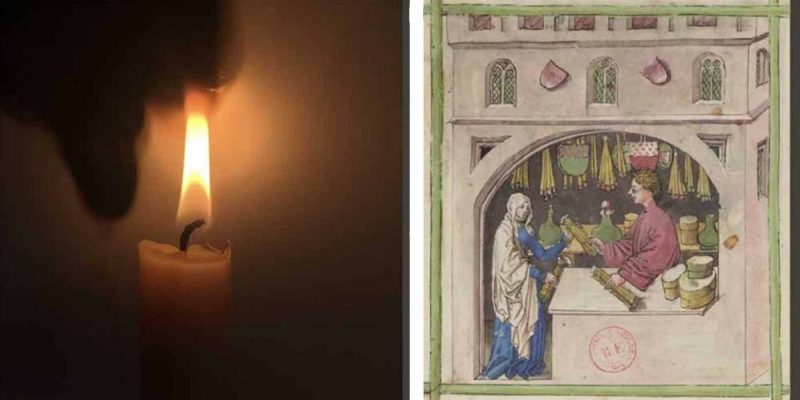

In the presence of oxygen and an external source that provides sufficient energy to start ignition (e.g., tinder, match, lighter), a flame is created. As soon as the process is self-supporting, the fuel is thermally decomposed and forms a variety of gaseous reaction products which further react and finally form the ultimate end products of combustion: water and carbon dioxide. During this process, energy is released as heat and light. The orange-yellow light in the upper part of a flame indicates that the organic material, e.g., candle wax or wood, is in the process of burning. The colour is induced by an intermediate product, soot, consisting of pure carbon particles.[4] These particles anneal and in this state become visible as flame. If the burning process is interrupted in precisely that state (incomplete combustion), for instance by introducing a metal spoon into the orange-yellow part of a candle flame, or by placing a fire-proof bowl close above the flame, soot deposits on the cold surface. This process is many times described in historic sources to produce black soot pigments. The cold surface should be very smooth, otherwise the fine soot particles are difficult to remove after cooling when the soot is collected by sweeping it off with a feather or by brushing. Large-scale production of so-called lampblack started with the increasing demand for printing ink from the sixteenth century onwards. To achieve a maximum yield, it combined a low-burning fire of resin-rich wood parts with a horizontal chimney to create a fractioned precipitation of soot particles in a special chamber. This allowed for various qualities of soot, ranging from the most expensive pure, deep-black soot to cheap and impure products.

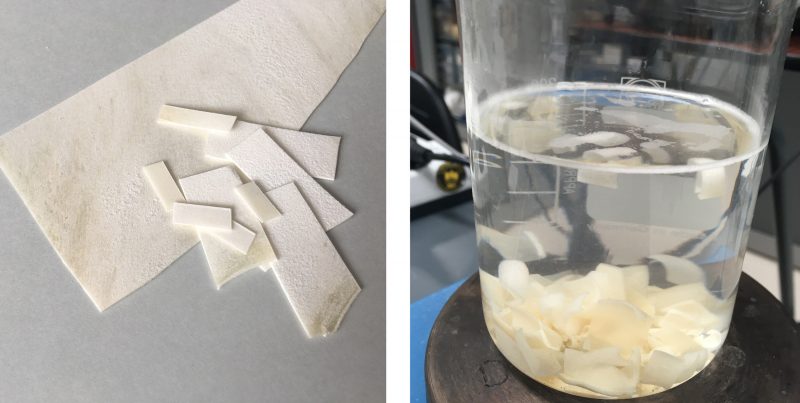

Soot has the advantage that the particles are already so extremely fine that they do not require additional grinding, in contrast to most other raw materials. Soot particles are very light and float on the surface of water, where they form clusters. They are static and do not easily disperse in water. Preparation of a good-quality soot-based watercolour or ink requires a binding medium that enables homogeneous dispersion. Thorough dispersing through mixing the binding media with the soot provides the best quality. This is usually done with a muller on a stone.[5]

Depending on several factors, often not only soot particles, but other volatile by-products, especially tar-related products, as well as inorganic ashes precipitate together with the soot. If tar-related impurities are present, the colour of the final product tends towards brown shades rather than black. While pure soot consists of pure carbon which is ambiguous for identification of its origin, contaminations might provide evidence to infer the raw material used to produce the soot. The interaction with aqueous media can be negatively influenced due to the hydrophobic nature of many tars. These impurities could be removed by washing in solvents or by applying a subsequent burning step, as elaborately tested by Lewis.[6]

1.1 Soot of Beeswax

[Reconstruction] [Recipe: Le Begue (1431)]

“Fumus est color niger, si cum ab igne candele sepi vel cere, vel a lampadis lumine exit, colligatur, qui aliter fuscus, et aliter fuligo nominatur.”*

Collecting soot from beeswax candles for preparation of black pigment is advised by the anonymous, late fourteenth-century author of De Arte Illuminandi[7]. While it is probably easily available to the modern reader, wax from bees was a precious product during the middle ages. Cera vergine, beeswax, was a relatively scarce product in Europe, reserved for centuries for church and court.[8] Apiculture was not yet broadly established and was limited to monastic and local bee-keepers, who struggled to supply the rather extensive consumption of candles for liturgical and political purposes, since one bee hive only produces about 0.6 kg of beeswax annually.[9] In central Europe, beeswax was an imported product, traded from Russia through the Hanseatic League, and from countries around the Black Sea, the Balkans, and North Africa via Italian and Spanish merchants, who shipped it to the harbours of Bruges and elsewhere.[10] It was a display of wealth and power for the citizens of Bruges that beeswax-candle bearers always preceded the procession when the Duke of Burgundy entered or left their city.[11] Beeswax was not only used for candles, but also for wax seals and for bronze casting.

While costly, beeswax was available via local sellers and was regularly purchased for artistic purposes by the Burgundian court. The ducal records are a rich source of information regarding trade of artists’ materials, including beeswax, in the Burgundian dukedom. In 1385 for instance, four pounds of wax were acquired from Poissonnier, an espicier in Dijon, for artistic purposes.[12] With a modal price of 48 deniers per pound, wax was much cheaper than the most precious pigment, ultramarine (30,720 deniers/pound), the expensive vermillion (160 deniers/pound), and even cheaper than a good-quality lead white (80 deniers/pound). [13] One record is especially interesting, since it tells of the purpose of the purchase: in April 1399, 10 pounds of wax candles were bought from Perrenot Berbisey, a merchant in Dijon. They were designated for the court painter Jean Malouel, then also situated in Dijon, to allow him to work by night.[14] Clearly, then, beeswax was available to artists in Valois Burgundy, and even for non-clerical applications.

Besides allowing nocturnal artistic work, beeswax might indeed have served as a source for obtaining smaller quantities of black pigment, especially in the monastic scriptoria, which had their own beekeeping. Le Begue (1431) distinguishes the soot of candles from wax and tallow under the lemma Fumus.[15] Producing soot from beeswax candles is associated with some unexpected challenges that only became apparent during the reconstruction.

1.2 Soot of Animal Fat or Tallow [Recipe: Le Begue (1431)]

“Fumus est color niger, si cum ab igne candele sepi vel cere, vel a lampadis lumine exit, colligatur, qui aliter fuscus, et aliter fuligo nominatur.”[*]

A cheaper version of wax candles were candles made from tallow. For centuries, tallow candles and oil lamps constituted transportable sources of light, affordable even for common people, though they were notorious for their unpleasant smell. Specific tallow-chandlers guilds were formed in European cities from the thirteenth century onwards, including, for instance, The Worshipful Company of Tallow Chandlers which was established in London around 1300. [16] Tallow candles were sold by candle merchants but could also be easily made at home.

The tallow is prepared by heating pieces of fat such as beef or mutton tallow, goat fat, or suet, for several hours until they are fully melted. The resulting liquid is strained through a sieve to remove impurities. Liquid tallow could be held in a fireproof bowl containing a wick made from tow or waste yarn, and would congeal at room temperature. (A re-working of the process can be found in a helpful tutorial produced by Wienische Hantwërcvrouwe, 1350). Another method was to dip a wick repeatedly into the warm, liquid tallow, building up the candle to the size and thickness wanted.

It is strange that, despite their widespread use, just a few recipes refer to tallow candles. Le Begue (1431) specifies soot from tallow candles from that of wax candles under the lemma fumus in his table of synonyms at the commencement of his manuscript.[17] A fifteenth-century German recipe refers to lights made from Unschlitt (tallow), but not for soot production, but only as a source of heat to melt frankincense to obtain soot.[18]

1.3 Soot of Lamp Oil [Recipe: Cennini (1390)]

“Another black is made in this manner: take a lamp full of linseed oil, light the lamp and put it under a clean baking-dish, so that the flame of the lamp shall be about the distance of two or three fingers from the dish, and the smoke which comes from the flame shall strike against the dish; collect the smoke together; wait a little; take the baking dish, and sweep off the smoke (which is the pigment) into paper, or into some vessel; it does not require grinding, because it is already a very fine powder. Thus you may continue to fill the lamp with the oil, put it under the dish, and make in this manner as much color as you require.”[*]

Black soot pigment could also be produced from an ordinary oil lamp. Oil lamps were filled with locally available oil, and even rancid oil worked well. A representative description of a soot preparation process from linseed oil is included in Cennino Cennini’s Il libro dell’arte, where he explains that one should ‘take a lamp full of linseed oil, light the lamp and put it under a clean baking-dish, so that the flame of the lamp shall be about the distance of two or three fingers from the dish, and the smoke which comes from the flame shall strike against the dish; collect the smoke together; wait a little; take the baking dish, and sweep off the smoke (which is the pigment) into paper, or into some vessel; it does not require grinding, because it is already a very fine powder. Thus you may continue to fill the lamp with the oil, put it under the dish, and make in this manner as much color as you require’.[19]

Oil of hemp or beetroots for making a black watercolour which also served as drawing ink were mentioned in the South German Liber illuministrarum, a late medieval manuscript from Tegernsee monastery.[20]

Ink makers from Eastern Asia still practice their ancient craft of producing soot from vegetable oils for calligraphic inks. They choose specific types of oil to produce distinct shades of black. Krünitz in 1820 provides a description of the process: to produce soot on a larger scale, the Chinese have purpose-built houses that are divided into small chambers. Each chamber contains numerous burning lamps of one type of oil which are maintained from early morning until late at night. The oil lamps are covered, and the soot is collected regularly, similar to the European method.[21]

1.4 Soot of Wood

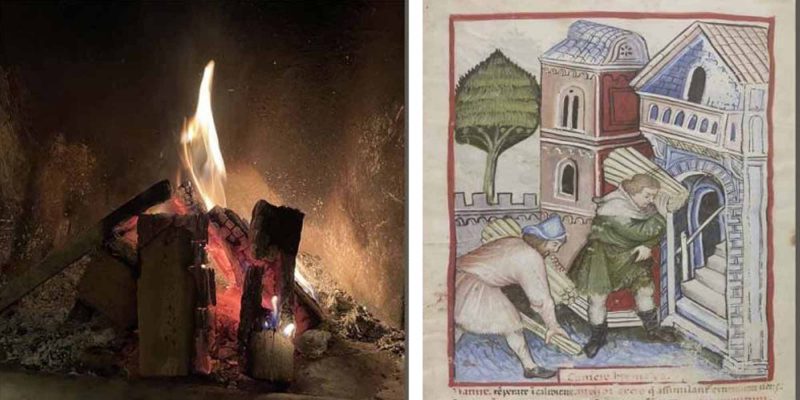

Wood-burning fires are the most ancient source of heat and light. Soot precipitates on hearth walls, in chimneys, and on cauldrons and may originate from any variety of wood. Depending on the circumstances, the obtained soot can feature a variety of shades and properties, ranging from purest, finest, black carbon particles to brown glossy lumps.

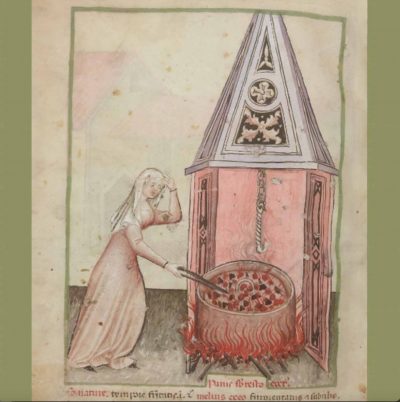

1.4.1 Cauldron Soot [Recipe: Codex Germanicus 1 (1454-1463)]

“Jtem wiltu schwartz farw temperiren ze entwerffen oder zemālen So nim linden rom der an eim kessel wachs oder ainem rochloch oder wie der rom ist das er lind vnd gutt sy vnd clain geriben.”[*]

Soot that deposits externally on cauldrons was an easy and cheap supply of a black colour, hence it is not surprising that the use of ‘soot that grows on a cauldron or at a smoke-hole’ is proposed in an anonymous manuscript from Southern Germany, which explains that such soot is useful: ‘[i]f thou like to temper a black paint for designing or painting’.[22]

1.4.2 Soot of Fireplaces and Chimneys (Caligo, Fuligo, Bister) [Reconstruction]

“Vom gereinigten Ruß. Wenn du aber gereinigten Ruß machen willst, dann nimm von den kleinen braunen Rußknollen so viel du willst und lege sie in Lauge und laß sie um ein Drittel einkochen und laß den Topf dann zugedeckt stehen, dann fallen die Verunreinigungen alle zu Boden und das obenstehende Wasser hat eine schöne feine Haarfarbe, worauf man sie auch aufstreicht. Und wenn man das Wasser gebrauchen will, dann gieße so viel du benötigst aus dem Topf und gib Gummi dazu, so daß die Farbe glänzend wird. Und streiche das auf, worauf du willst und schattiere damit Gewänder oder Steingebirge, denn sie ist gut zum Malen vieler Dinge und zu mancherlei Schattierung.”[*]

Soot and the various side products of incomplete combustion deposit on the side walls of hearths and fireplaces. Also, they precipitate as hard, glossy clumps within chimneys which pose a fire hazard and therefore have to be removed regularly by the chimney sweeper. The first mention of bister is usually ascribed to le Begues’ manuscript of 1431, where it is included in his table of synonyms as caligo and fuligo.[23] Yet other earlier sources mention the use of ‘small brown lumps of soot’.[24]

The composition of bister depends on the type of wood that was burnt and can differ considerably.[25] Beside carbon particles, bister contains many brown-coloured organic contaminants, which are the reason that bister is usually of a blackish-brown colour, which can tend towards intense brown, or orange-brown shades. Le Begue even refers to a ‘dark saffron yellow’ colour.[26]

Bister from resin-rich softwood leaves glossy residues on fireplace walls, hence the German name Glanzruß [Figure 8]. These glossy tar-related, resinous substances are poorly soluble in water, properties that were undesirable for watercolours, as Ruffach warns in 1549.[27] Bister has a characteristic smoke smell reminiscent of a campfire.

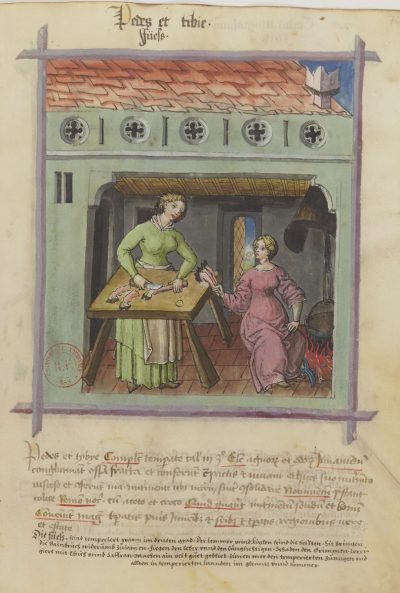

Some early recipes, as for instance the one in the Colmarer Kunstbuch, suggest that dyemakers ‘purify’ the bister by washing it in lye and concentrating the solution by boiling it down. Impurities sink to the bottom and the remaining solution can be used. Other authors advise to add water and let it ‘sieden up die helfte’ (boil down to half) and finally add some alum.[28] Bister was ascribed healing properties, therefore it was sold in pharmacies, as a late fifteenth-century illustration of Fuligo in the Circa Instans, seu de medicamentis simplicibus by Plaetarius depicts. Bister is especially recommended for painting hair and beards.[29]

1.4.3 Soot of Conifer Wood (Lampblack)

“Kün schwartz ist jederman bekant.”[*]

Burning wood of coniferous trees provides another sort of soot, in German sources referred to as Kienrußschwarz or Kienschwarz. The English term lampblack literally refers to soot of (oil)lamps, but misleadingly became widely established as the common name for the soot of conifer wood.[30] The wood of coniferous trees contains a large amount of resins which makes it suitable as tinder, but also rendering a quite beautiful soot-black. After 1450, when printing with movable metal types was invented, lampblack became the principal soot-related black pigment because it was suited perfectly for book-printing ink. The forest-rich region of Thuringia in Central Germany and later also Scandinavia[31] became the major producers of lampblack.

Kienruß-furnaces were built by the side of pitch furnaces directly in forest areas in order both to avoid the labourious transport of wood and to use up the wastes of pitch production. All conifer wood parts that could not be used otherwise, like roots, barks, needles, stumps etc., were used as raw material for the production of lampblack. German Kienruß-furnaces had a special design to separate fractions of soot differing in quality. These furnaces were able to produce very pure soot of high quality as well as of lower qualities [Figure 9]. Krünitz makes an interesting remark when discussing Chinese ink production, emphasizing the marvelous quality of black soot from burning spruce wood, which interestingly is also the major source of Kienruß production in Thuringia, in central Germany.[32]

The poor families of the Thuringian forest regions supplemented their incomes by fabricating chip-wood boxes made of fir-wood with a sliding lid for packing smaller quantities of lampblack.[33] Larger quantities were sold in vats of differing size.[34] Traded all over Europe in large quantities, lampblack came in various grades of purity. The best quality was used in typography as book-printing ink and consisted of finest pure carbon particles and therefore had an intense black colour and a significant coverage quality. Lower qualities could contain larger soot particles or even bister-like residues and were used by shoemakers and house-painters. Even lower qualities were used in the ship industry for coating ship hulls. Therefore, the major sales markets of the Thuringian carbon black manufacturers were Great Britain and the Netherlands, who, besides the low qualities for shipbuilding, were also in need of good black pigment for their book printing centers.

Even before mass production started around the beginning of the seventeenth century, lampblack was already a well-known pigment. In the mid-sixteenth century it was so commonplace that Boltz van Ruffach, who extensively discussed several black pigments in his Illuminier Buoch (1549), dedicated just one sentence to this pigment: ‘Kün schwartz ist jederman bekant‘ or ‘pine-soot black is known to everyone’.[35] It was already mentioned as a pigment for the preparation of black wax in the Liber illuministarum (1450/1500-1512) [36] and was most probably at the disposal of Burgundian illuminators who might have appreciated its special properties.

1.4.4 Soot of Birch Bark [Reconstruction] [Recipe: Codex Germanicus 1 (1454-1463)]

“Wer aber das du des romß nit fȗndest, so nime birkin rinden vnd brenn sy an aim fȗr vnd stu̇rtz ain bekin darȗber oder ain glest kachel, das der tunst daruff mutt gon und der rom der daran wachst, der ist recht gutt.”[*]

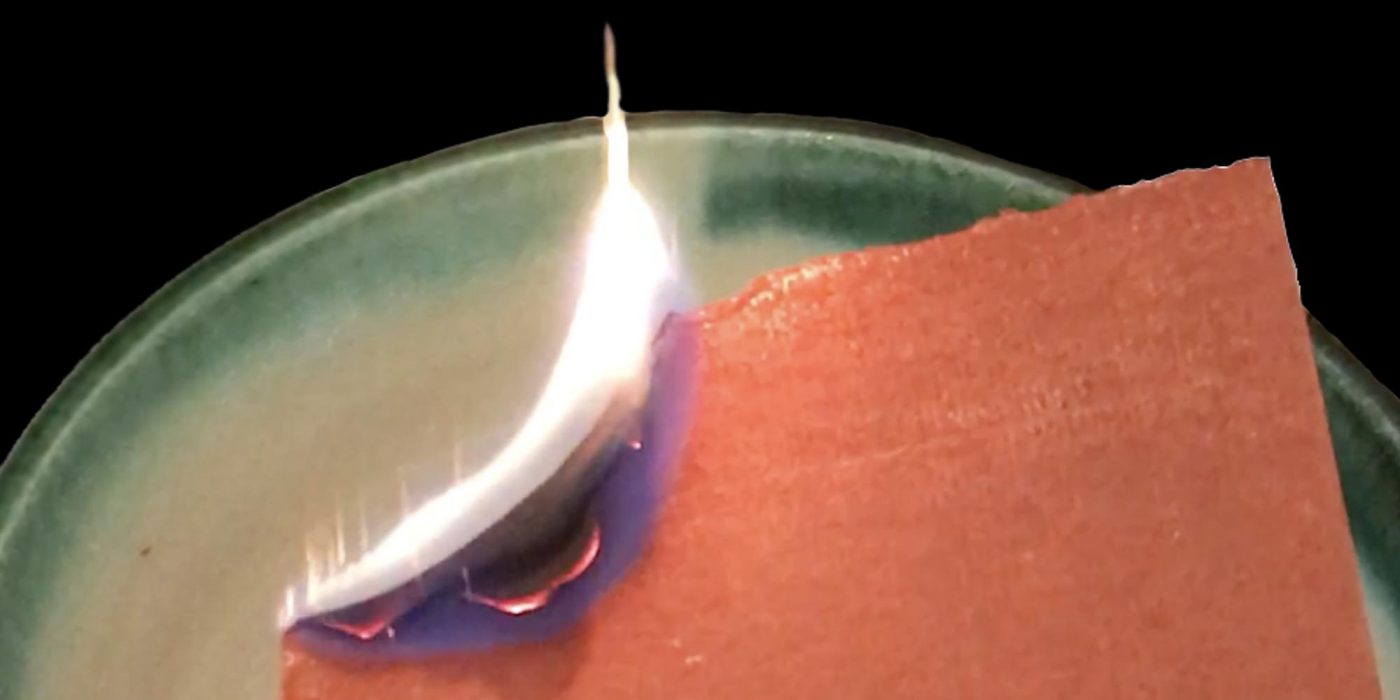

Some types of hardwood also contain resins, like beech (genus Fagus) or birch (genus Betula).[37] Birch bark is a natural tinder because it burns perfectly due to its thinness and its high resin content [Figure 10]. The author of a Swabonian manuscript suggested it made particularly good soot when he noted around 1450:

But if you don’t find any soot, take birch bark and burn it in a fire and cover this with a small pot or a glazed earthenware vessel, so the smoke must touch it. The soot that grows on it is quite good.[38]

Reconstructions showed that birch bark burns instantly, with strong smoke development. In some cases, glossy, resinous products deposited with the birch bark soot.

1.5 Soot of Resins

Many types of wood contain resins, including both softwoods and hardwoods. Coniferous trees are especially known for their high resin content, which makes them useful for production of pitch and tar, and as sources for the production of black soot pigments. Resins are an additional source of carbon and therefore resin-rich woods produce more soot than woods without resin. Some resins were famous for their fragrance, like frankincense, myrrh, and mastic. They were highly esteemed import products. Most resins have a medical application and therefore are included in medical treatises. They were sold in pharmacies.

1.5.1 Soot of Frankincense[Recipe: Hs 181503 (1451-1500), Nuernberg]

“Item. Mache eine grosses Licht von Unschlitt (Talg) in einem Tiegel und zünde das an und spalte ein Stäbchen auf und tue Weihrauch dazwischen und halte das unter ein Becken was darüber gestürzt ist und brenne den Weihrauch in dem Lichte, so setzt sich Russ an dem Becken ab. Den streiche mit einer Feder ab und nehme Harz von Arabien

[Gummi Arabicum] und lege das in Wasser das es sich auflöse und mische das dann darunter, das wird einer schöne wunderbare Fabe, mit der Du färben kannst was Du willst.”[*]

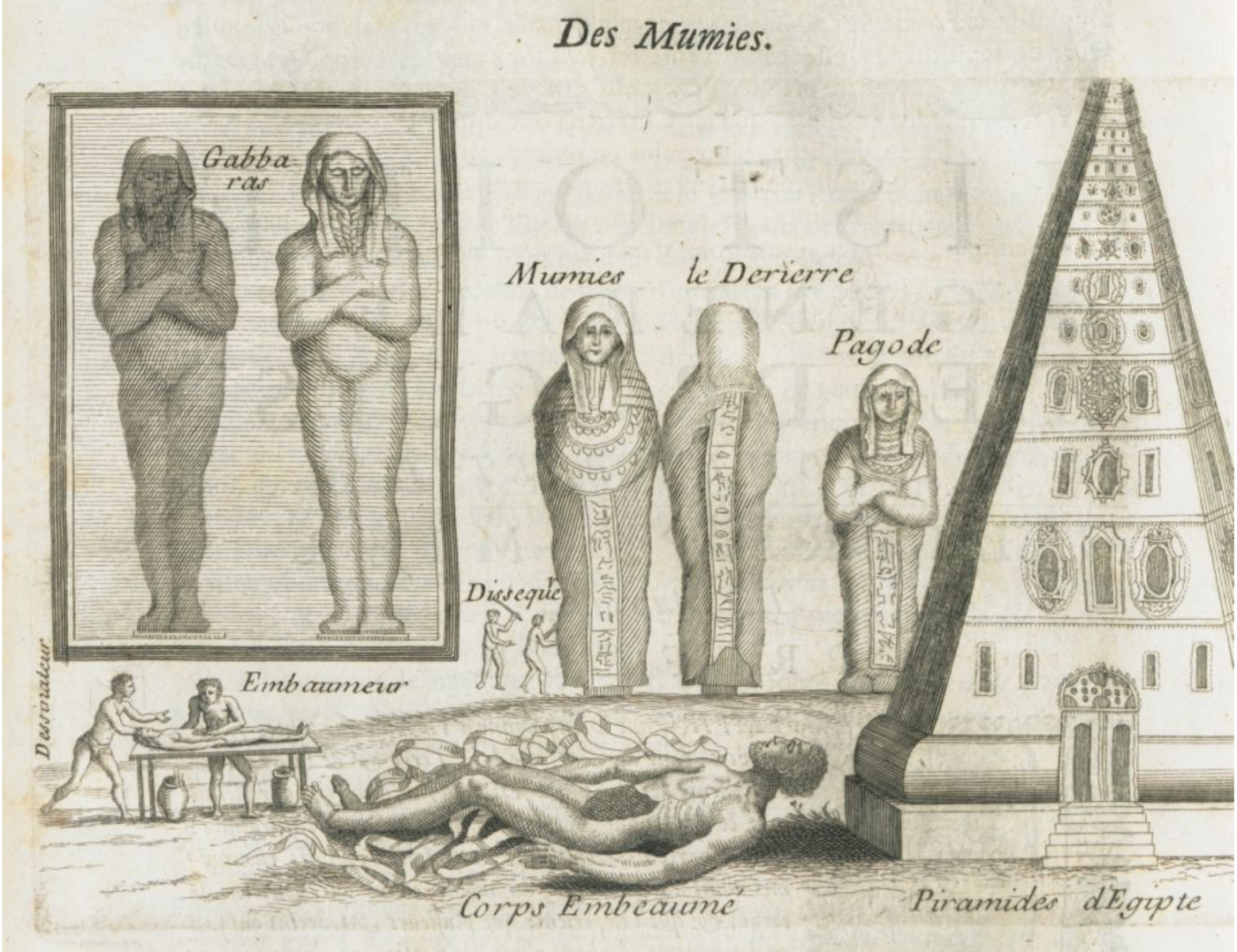

A precious source of soot, closely tied to monastic use, was olibanum or frankincense. This fragrant resin is a product of trees of the genus Boswellia and had to be carried all the way from the Arabian Peninsula, north-east Africa or India [Figures 12]. Frankincense is mentioned in two German treatises written in the second half of the fifteenth century. The recipes direct users to fill a bowl with either animal fat[39] or oil[40], add a wick, and ignite it. The compiler of Liber illuministarum, working in a monastic environment, suggests putting a piece of frankincense ‘alz groß alz ain halbs ay‘[41] — the size of half an egg — onto the wick of an oil lamp. This amount is rather large for a natural resin, and the wick would need be considerably thick to keep such a large piece in place during burning. The cited German manuscript, HS 181503, includes instructions for another procedure: to split a rod, insert a piece of frankincense, and hold this over the flame. In both cases a bowl is installed on top to collect the formed soot. After cooling, the soot is swept into a clean pot with a feather.

1.5.2 Soot of Coniferous Resin (Noir de Paris) [Recipe: Kölner Musterbuch (1490)]

“Item flamswart toe maken. Neem dycke lemmyt van groeven tauwe als een swanenveder ende cleme daer harse om als een eynde van I kersen unde settet under I becken ser scoen ghescurt, ghestolpet op iij halve backen steen ende wil mens vole hebben so mach men om dat kersken legghen iiij stacke herse in een kannenschaert off in een latel panne ende latet wtbemen ende dan vechtet van den becken ende wrijstet wal myt watter also langhe al rubrijck ende steeckt op een krijt ende lattet drugen ende doet in een busse.”[*]

Less exotic, but related to frankincense, is the resin of many European trees. Coniferous trees are especially resin-rich, and they even contain distinctive resin canals. Resin is naturally exuded by injured trees; it seals their wounds and has a protective function [Figure 13]. By deliberately cutting the bark of trees, a substantial amount of protruding resin can be collected throughout a year. The resin requires further cleaning by melting and straining. It was used in as incense and in medicine and was depicted in early printed medical treatises like the Hortus sanitates, an incunabulum printed in Mainz in 1497. Burning the resin of pine, spruce, or fir trees produces a soot-rich smoke, an excellent precondition for pigment production. In 1431, le Begue included an antique recipe in his compilation of copied art-technological treatises, where resin is burnt indirectly on hot tiles to obtain a black pigment.[42] Resin could also be kneaded around a wick, placed between additional resin in a fire-proof earthenware container and ignited. Upon completely burning the resin, the soot was collected on the surface of a clean bowl that was set upside down on three bricks, as the cited recipe in the Kölner Musterbuch (1450) written by hand in Northeastern Middledutch reveals.[43]

Larger-scale soot production from resin of coniferous trees began in Europe with the introduction of book printing.[44] This process was carried out in specifically-built small shacks, in which cauldrons full of resin or pitch were placed, ignited, and the evolving soot collected on stretched animal skins or canvas lined with paper.[45] In this way, larger amounts of what was then called noir de fumée leger or noir de Paris were made. This product was misleadingly also sold under the name lampblack.[46]

“…consumed with fire is made a blacke colour, as we may see in Charcoales, Oyle, Pitch, Linkes, and such like fattie substances, the smoke whereof is most blacke” [*]

In wood-rich areas of Scandinavia, Central Germany, and France, resin of coniferous wood was extracted on large-scale by dry distillation. Wood was stacked in specifically-built ovens with an external heat source.[47] The high temperatures caused the resins within the wood to melt, and they were collected as so-called pitch. Viscous pitch was further heated to produce the nearly solid, black-coloured tar. Tar and pitch render all kinds of materials waterproof and therefore were abundantly available, especially in harbour cities, proving indispensable for the shipbuilding industry. Both materials could be burnt directly in pans, as described above under ‘Soot of Coniferous Resin’; doing so produced lampblack which was also known as Noir de Paris.

“Nigrorum & obscurorüm species: […] Pinastrj. […] accommodarij Nigrum Pinastry, vstumi ebur seu cornum ceruinum Carbones, Tilius, quandoque ex multis malj prefioj terr[arn] coloniensem & fuliginem.” [*]

Burgundy pitch is a specially prepared resin of the spruce (genus Picea). It is unknown if it was available in the fifteenth century, but is included here as one potential source for soot making in Burgundy.

“Modo di fare el nero da stampare e libri optima: Fa un lanternone largo per ogni verso un braccio et quarto et alto cinque o sei braccia, et incartalo di carta bombagina o pecora nou importa; et da pie fa che habbia uno sportello et mettivi un tre pie et in sul tre pie un tegame ; et nel tegame due libre di pece greca et metti fuoco nella pece, et serro lo sportello, et fa che el lanternone non sfiati da alcuna parte, et lascia ardere, tutto el fumo che riesce s’ appicha per il lanternone, a uso di filiggine ; alhora cava el tegame et el tre pie, et sera lo sportello, poi batti di fuora el lanternone con una bacchetta, et quella materia chaschera in fondo, lasciala riposare, poi la cava et serbala et se tu vuoi meglio nettare il lanternone, in sur una bacchetta legate penne di gallina et spazalo dentro per tutto, et questo serba col primo”[*]

A particular fraction of pine resin is further processed to Greek pitch, colophony, which was used after 1450 for producing soot for printing inks.[48]

1.5.6 Soot of Torches (Sable) [Recipe: Bate, The Mysteries of Nature and Art (1634)]

“To make a fuime black called Sable. Take a cleane latten basen, and hold a burning torch under it, untill the botome be black, and then take of that blacke, and temper it with glayre or with Gumme water, and so worke with it.”[*]

The flammability of tar and pitch made them ideal for impregnating the tops of torches. The Montpellier Liber diversarum arcium refers to soot of pine-torch collected in a cuprous vessel, stored in a well folded page, and used as pigment for preparing a black ink.[49] It is assumed that torches were a rather easily available source for preparing black pigments. Several publications of the sixteenth and especially the seventeenth century include soot of torches as a watercolour pigment, for example, the recipe quoted at the beginning of this section from the book The Art of Limming, published in 1596.

Class 2: Chars

Chars play an important role as black pigments. Well known are pieces of charcoal, charred wood, which can often be found in the ashes of wood-fueled fires. Deliberate production of charcoal was a precondition for the ability to smelt iron ore.[50] Charring is a specific process of thermal decomposition, irreversibly changing the chemical and physical properties of organic materials.

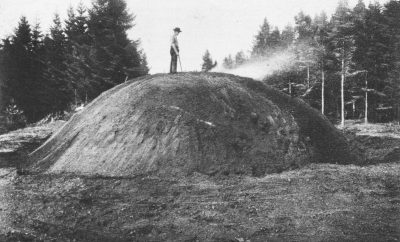

The charring process differs essentially from soot production. During charring, oxygen is deliberately excluded with the aim of manipulating the combustion process (i.e. charring takes place in anoxic conditions). This anoxia is realized by heating the raw material in a nearly air-tight environment, for instance by putting the raw material into a fire-proof crucible which is placed in a fire. Another process is the ancient technique of large-scale production of charcoal where a closely-stacked wood pile is covered with a layer of muddy clay and ignited internally [Figure 18]. When charring, one must be sure to vent the container so that gasses may escape, which is why the process is only ‘nearly’ air-tight.

The charring process passes four phases:

1) Drying: At 100°C the non-chemically bound water evaporates.

2) Thermal decomposition: Once a temperature of 280°C – 300°C is reached, organic compounds undergo a rapid thermal decomposition, chemical bonds break, and non-carbon elements like hydrogen are released from the carbon chains to form gasses which escape, causing a considerable loss of mass. These chemical reactions continue with increased temperatures, but at a lower rate. The thermal decay is specific for different materials, like for instance bone[51] or wood.[52] Flame formation and further combustion are impeded by the absence of oxygen.

3) Carbonization: The remaining material, which cannot further incinerate, starts to change its chemical structure, a process called carbonization. During that stage, the carbon framework starts to reorganize.

4) Cooling: Finally, during the cooling phase, the carbon re-crystallizes. It forms a graphite-like structure that causes an increased absorption of electromagnetic radiation, and hence the material appears black.[53]

After charring, the outer structure of the material remains unchanged, but is shrunken due to the loss of organic matter; the material at this point is entirely black. All inorganic components remain, and play an important role in scientific identification of black char-based pigments.[54] Depending on the initial strength of the material, charred structures can be quite solid and need pounding in a mortar and thorough grinding before they are suitable as pigments.

According to historic recipes, four major groups of charred materials can be distinguished: (1) wood, (2) shells and pits of nuts and fruits, (3) vine lees and pomace, and (4) bones, horn, and ivory.

2.1 Charred Wood and Charcoal

“Kol Swart. Van houdt colen maekt men een blouw offt grauw swardt / alsmen die wel clijn vrijft, en opt crijt laet verdroogen.”[*]

Charcoal burns without smoke, because all organic components that could form gasses are already lost during the charring process. Burning charcoal reaches higher temperatures than uncharred wood yields. Therefore, it is of special interest to all professions that require high temperatures like blacksmiths, goldsmiths, lime burners, and potters. Charcoal is included in many artisan treatises as fuel for specific purposes.

All types of wood can be processed to charcoal. The initial hardness of the wood is retained after charring. For this reason, oak wood is not recommended as raw material for black pigments.[55] Instead, softer wood species are preferred. In 1431 Le Begue lists carbo in his tabula de vocabulis sinonimis et equivocis colorum, black pigments made from charred wood of willow, poplar, vine, and similar soft woods.[56] Other authors just use the generic term charcoal as a source of black pigment, often without specifying the source of wood.[57]

2.2 Charred Vine, Willow and Basswood [Reconstruction]

Already in the fourteenth century, the Montpellier Liber diversarum arcium, specifies charred vine (genus Vitis) or willow (genus Salix) as preferred raw materials for the black paint of illuminators. According to Marc Clarke, the black of these chars is referred to in earlier sources as nigrum optimum, ‘the best black’.[58] Later sources recommend charred wood of willow as well.[59] Crayons made of charred twigs of vine or willow belong to the average toolbox of fifteenth-century artists, and are perfect tools for drawing and underdrawing. It is known that charcoal crayons break easily and therefore can be effortlessly ground as a source of a black pigment. Tendrils and twigs of vine plants were also burnt directly to obtain a black pigment, however this causes quite a loss of material.

The late medieval Liber Illuministarum includes charred linden tree soot, but as a pigment used in primers for gilding, not as black watercolour.[60] A series of Latin recipes in MS Sloane 2052 in an anonymous hand lists carbones seq. Tilius, the charred wood of the linden tree (genus Tilia).[61]

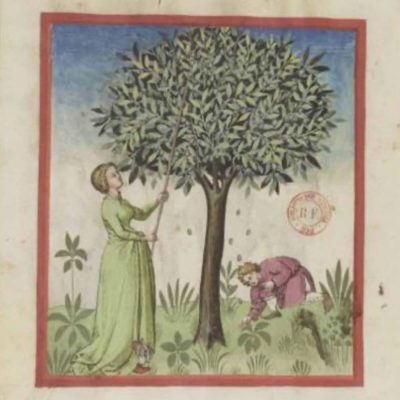

2.3 Charred Fruit Pits and Nut Shells

Little was wasted in the middle ages, and pits and shells of fruits and nuts could be recycled through charring. While collecting those is confined to the harvest season, they can be stored in dried form until processing. Charring was carried out in closed crucibles.[62] After charring, shells and pits keep their initial hardness, hence they require crushing in a mortar before they can be ground on a stone. Grinding on those ‘stones’ is quite labour-intensive.

2.3.1 Charred Peach Pits [Reconstruction] [Recipe: Ruffach (1549)]

“Pfirsichstein Schwartz. Wiltu ein gar zart unnd lieblich schwartz haben. So nim Pfersichstein / thun die in einen nüwen hafen / thun ein fynen behäben deckel doruff / den verkleib gar wol das kein dampff daruß möge / es würden dir sunst die stein zu ytel äschen werden. Den hafen gib einem hafner der brennen will / das er dir den zu andrem gschirr in ofen setz zu brennen. Wann er dann gebrant hatt / so nimm den hafen unnd thun jn uff / so sind die stein kol schwartz. Die zerstoß in eim mörsel gar klein / unnd ryb sy gar lang unn wol / uff einem stein / biß sy nimme ruch sind. Temperier sy darnach an mit welcher temperatur du wöllest / so hastu gar ein schön gut schwartz.”[*]

Of all fruit pits, those of the peach (Prunus persica) are certainly the most frequently recorded source for black watercolour pigments. Two fifteenth-century recipes for black pigment, both of Mediterranean origin, refer to peach pits. They make a ‘perfect and fine black’.[63],[64] Boltz von Ruffach explains the process clearly in the Illuminier Buoch: ‘So take peach kernels / put them in a new pot / and put a fitting lid on them / the lid should be sealed so that no steam comes out / otherwise the kernels would become completely ash. Bring the pot to a potter who is going to a kiln / so that he adds it to the other pottery in the oven. When he finished burning / so take the pot and open it, then the stones are coal black. These pound in a mortar very small / and grind long and well / on a stone / until they are no longer rough. Then temper it with which binder you want / so you have a nice good black’.[65]

2.3.2 Charred Cherry, Apricot, and Date Pits [Reconstruction]

“Noyaulx de Cerises brusles & reduicts en charbon dans vn creuset couuert…”[*]

Sir Theodore de Mayerne’s discourse with Mr. Huskins, an excellent illuminator, of March 14, 1634, includes a recommendation of cherry black, ‘reduced to carbon in a crucible’.[66] While cherries (genus Prunus) were available, their pits are not mentioned in recipes before 1600. However, later sources list cherry stones frequently as raw material for black pigments,[67] as with pits of apricots (genus Prunus) and dates (genus Phoenix). Peacham in 1634 lists Date stones burnt under “These be the blacks which you most commonly use in painting”, suggesting that sufficient date stones were available in London by then to produce at least smaller amounts of black pigment.[68]

“Neempt persen oft abricocken steenen met de keernen / soete oft bittere amandelen met harde schelpen / ende veel beter zynse met de keernen / dan sonder keernen.”[*]

Kernels of almonds are surrounded by hard shells. Several Italian authors of the fifteenth and sixteenth century refer to almond shells in their recipes for black pigments; these shells were burnt or charred either with the edible kernels, or without.[69] Piemontese in 1561 suggests the use of either sweet or bitter almond shells, but ‘if the kernels are inside, it is much better’.[70]

2.4 Charred Vine Lees and Vine Pomace

“Noir d’Allemagne. Nous saisons venir de Francfort, de Mayance, & de Strasbourg, un Noir en pierre & en poudre, qui est de lie de vin brûlée & jettée dans de l’eau & aprés avoir été seché on le passe dans des moulins faits expres, …”[*]

Other black pigments for watercolours were derived from charred vine lees, yeasts, and pomace. Hoogstraten in 1678 refers to ‘gebrande wijndroesem of druif kernen’ — ‘burnt vine pomace or vine kernels’ — [71] and in 1694 Pomet refers to burnt vine lees, describing ‘Black from Germany. It comes from Frankfurt, Mainz, & Strasbourg, as black stone & powder, which is burnt wine lees & thrown in water & after being dried we pass it through special mills. This waste product of wine making gained later fame as Frankfurt black, widely employed as a pigment for intaglio printing ink’.[72]

According to Krünitz, the pigment was traded via Frankfurt upon Main, a city with a century-long history of tradefairs, hence the name. He points to the fact that the French got Frankfurt black via Frankfurt, Mainz, or Strasbourg, which agrees with the statements of Pomet. Krünitz reveals that the black pigment was actually produced down the river Main, in Kitzingen, a protestant city in Franken, close to Würzburg, a region still famous for its white wine production. We also learn from Krünitz how Frankfurt black was made. The wine yeasts that remained in the vessel after the distillation of brandy are poured onto a coarse stretched cloth so that all remaining liquid can run off. The residues are then pressed into balls and left to dry in the air or in the sun. These dry balls are inserted into pots; the pots are covered with well-fitting lids, carefully glued with clay, put into a potter’s oven, and burnt with the other goods. After taking it out, the vine-yeast has burnt to a completely black charcoal, the so called ‘Frankfurt black’.[73]

2.5 Charred Pigments of Animal Origin: Charred Bone/Hartshorn/Ivory

“Le meilleur de touts les noirs, qui s’estend le mieulx, & duquel mestnes on peult glacer, est le noir d’yuoire, ou d’os de pieds de mouton, lesquels se mettent par pieces dans vn creuset, qu’il fault bien couurir d’une tuile ou bricque, & luter les joinctures si exactement que rien no respire; le tout sec soit mis dans vn bon feu, par l’espace d’vne heure seulement, (aultrement les os pourroyent blancher), & ainsi soit bruslée la matière a parfaitte noirceur.”[*]

Bone, ivory, hartshorn, tusk, and teeth materials are similar in their composition, and are used similarly in the production of pigments. As proven by archaeological excavations, these materials are remarkably durable and even survive extreme fires. They consist primarily of collagen, an organic compound, and of inorganic mineral components, including calcium hydroxyapatite with calcium and phosphor.[74] In complete combustion, bones and related materials lose all organic matter, and calcium hydroxyapatite remains, which is white in colour. As a result of incomplete combustion (charring) most of the organic components are lost, and carbon is formed and re-crystallizes into graphite-like structures. Together with the inorganic calcium hydroxyapatite, which also abides high temperatures, this charred bone forms bone black. The re-crystallization process (carbonization) of bone material starts above temperatures of 350°C, resulting first in brown-black coloured products. From 600°C onwards, changes in the crystalline structure occur and the remaining material is deeply black coloured.[75],[76] Charred bones, hartshorn, and ivory are very hard, and require proper pounding first, and then grinding on stone slabs before they can be used as a pigment.

2.5.1 Charred Bone (Spodium) [Reconstruction] [Recipe: The Göttingen Model Book (c. 1450)]

“Been swart. Het been swart is het besste swart datte gebruijk kan worden maar het moet langh gevreven worden met schoon regen water en met redelijk wat gom water getempert het is gemackelijk genogh te gebruijken …”[*]

Bones were common domestic left-overs, as we learn from Cennini’s recipe for the preparation of bone white: ‘take the bones of the ribs and wings of fowls or capons; and the older they are the better. When you find them under the table’.[77] Bone white, very closely related to bone black, is prepared by complete combustion, and was a conventional artists’ material in the fifteenth century. It served, for instance, as a coating of paper supports for metal-points, the dominating drawing material of the Burgundian period.[78] By excluding oxygen during charring, bone black could be produced, which around 1450 was considered ‘the best for illuminating’.[79] Care must be taken during charring so that no oxygen reaches the bones, because in that case the combustion continues, the carbon reacts to carbon dioxide, and the bone material turns white (calcium hydroxyapatite, i.e. bone white). This process can happen locally, usually close to the lid where air might enter. Such a side effect was well known, and is described by Mr. Mytens, a painter, who recommends using sheep feet to produce bone black and warns about ‘bleaching’.

Charred bones are mentioned under the term uulgariter Elpenswarcz (vulgar ivory black) in the Liber illuministarum to colour beeswax black.[80] The late sixteenth-century author of MS Fr 60 refers to burnt bones of the feet of oxen as the source of a black pigment, which, according to him, renders a blueish tone.[81]

2.5.2 Charred Hartshorn (Cornu Cervi Ustum)

“Take Hartes horne, and burne it to cole on a Coliars harth, then make fine powder thereof, and grinde it on a Painters stone, with the gal of a Neate. Then put it in a shel to drie in a shadowy place. And when you wil occupye the same, grynde parte thereof againe with the glayre, or with gumme water, and worke it forthe.” [*]

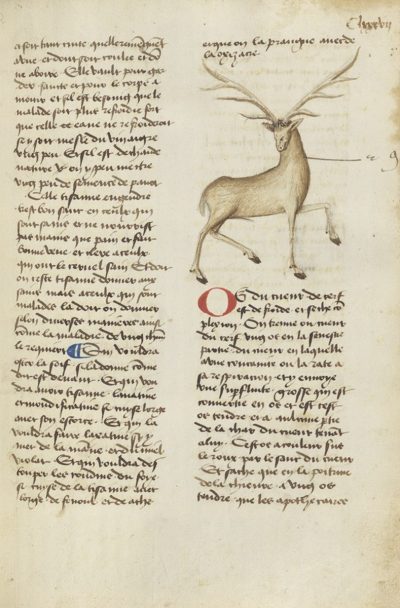

The antler of a male red deer, known as hartshorn, resembles bone in its composition and therefore its charred products are comparable to bone black. Reconstructions showed that hartshorn is extremely hard and it needed to be sawed to be broken down for the crucible. None of the consulted fifteenth-century sources contained a reference to charred hartshorn black, while several subsequent sources of the sixteenth and seventeenth century mention it as a watercolour pigment. Hartshorn was obviously known in the Burgundian period; Liber Illuminarum refers to burnt hartshorn white, stating that it is comparable to lead white, but less white than burnt ivory.[82] It was available via apothecaries, where it was sold as ‘cornu cervi ustum’.

2.5.3 Charred Ivory (Ebur Ustum) [Recipe: Mayerne manuscript (1620-1646)]

“Schwartz in Schwartz malen oder zuschreiben. Meister Lucas Churfs.’ Mahler zu Wittem= berg, hat under andern auch diss lob / gehabt, daß er den besten Sammet soll gemalt haben, darumb daz er in schwarz noch schwarzer, vnd auch allerschwarzst hat mahlen können dem Thue allso. Nimb bei einem Compassenmacher 1 h. helffenbeinen Abschnitten, thue es in ein unverglest seidl hefelein, deckh ein stürzlein darüber, verkleibs mit Leimen auf das aller genaust, gibs einem hafner, dass ers mit andern häfen die er brent einseze, So es nun auß dem offen wie andere hafen genommen wurt, brich die stürzen herab, heb dieselben gebranten stücklein helfenbein auf, stoss in einem Mörsern zu Puluer, wan du es zum schreiben oder mahlen brauchen willt, reibs unnder leinöl, so würstu sehen daz es schwerzer ist dan kein schwarz.”[*]

Ivory black plays an important role as a black pigment until the nineteenth century. Ivory, taken the tusks of elephants, form black reaction products through charring, and white through complete combustion, as other bone materials do. Ivory black was a luxurious substance and was made from leftovers of ivory processing, like the ivory filings of comb and compass makers,[83] as described in the cited German recipe for a ‘black that is blacker than no other black’, referring to Meister Lucas, Kurfürstlicher Maler (most probably Lucas Cranach the Elder or the Younger) who was praised for painting the best velvets and the blackest blacks.[84]

While many seventeenth-century authors mention ivory black as the source of watercolour pigment, only a few earlier references exist. A fifteenth-century reference is found in codex Latinus Monacensis, including an indirect note to ivory black as a pigment that mentions bone black as a substitute.[85] Surrogates for ivory are mostly ordinary animal bones. The tusks of mammoths, walruses[86], and the teeth of the sperm whale were used as well. Like bone, ivory is extremely durable. It was available in pharmacy shops as ‘ebur ustum’.

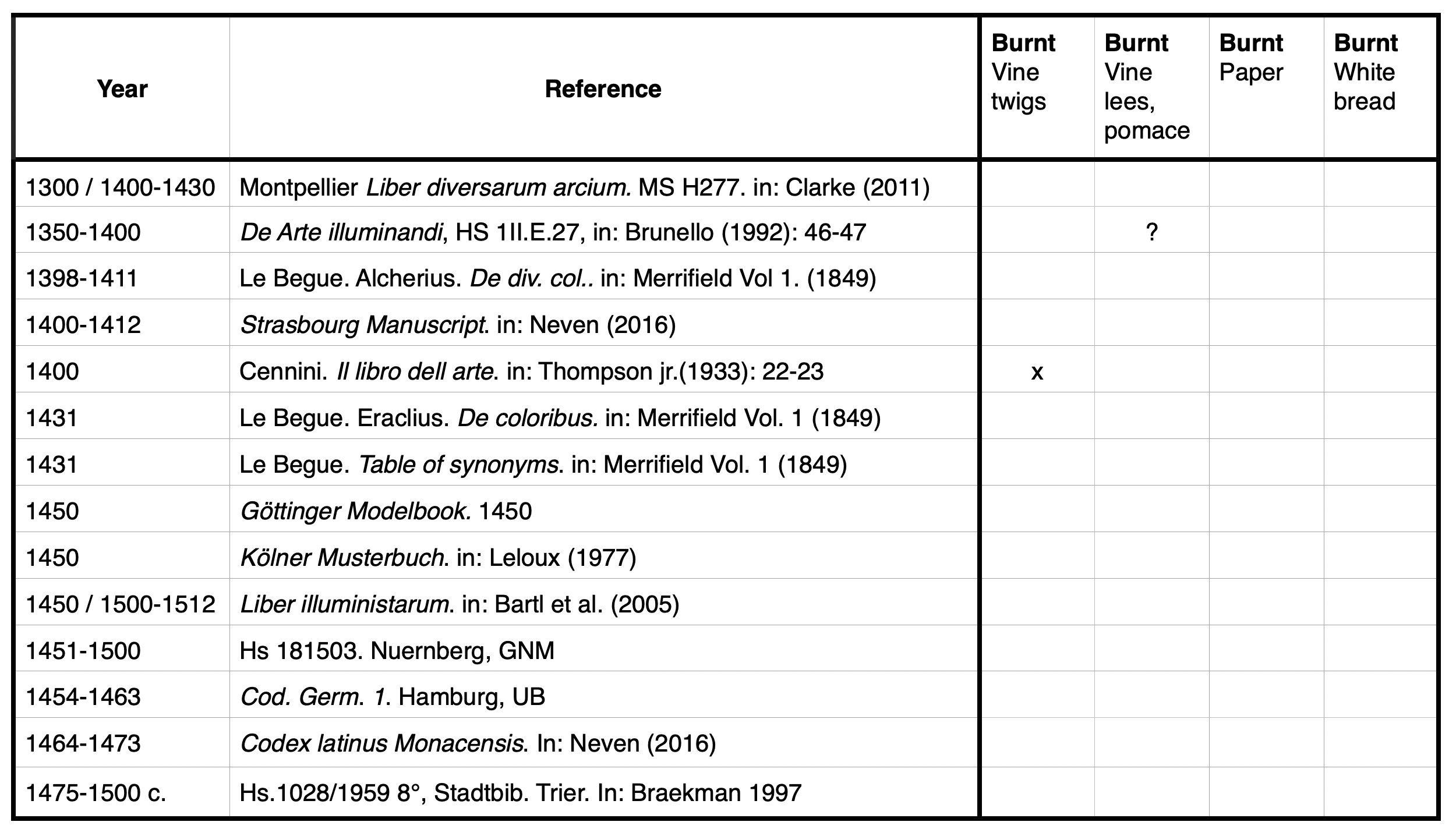

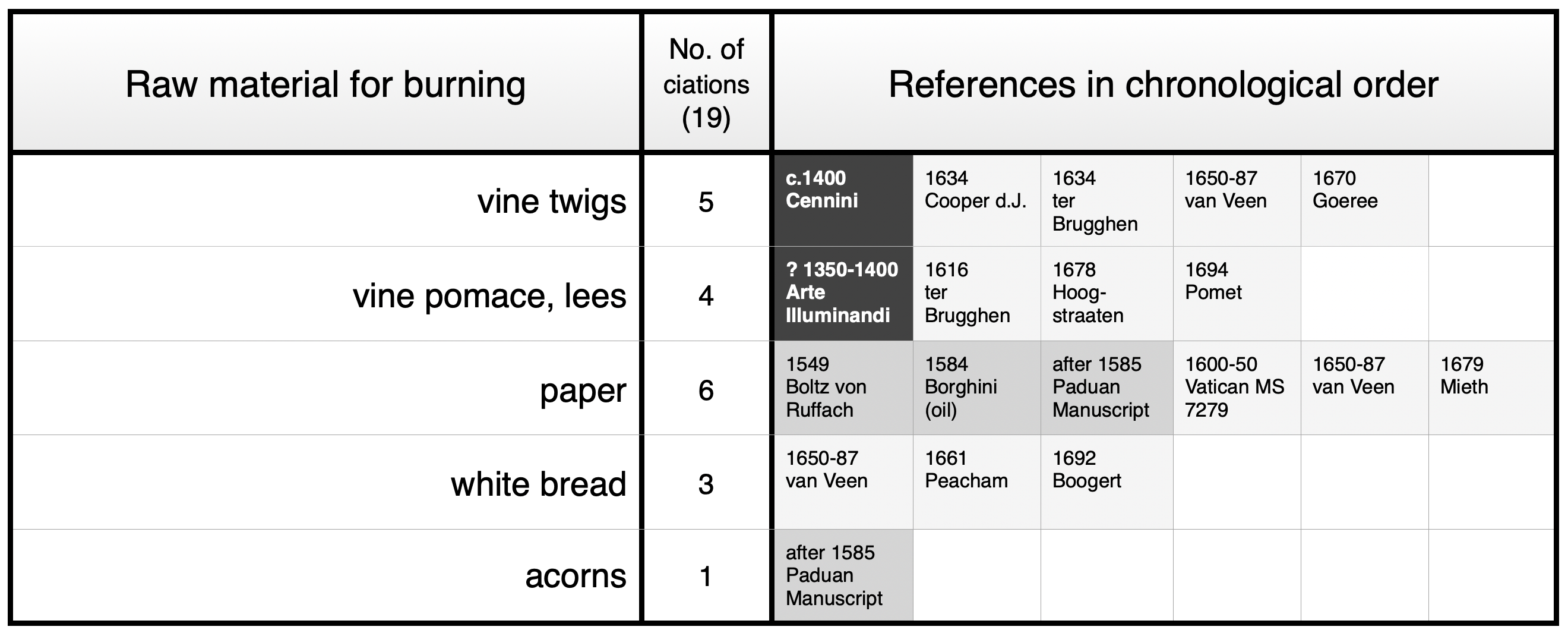

Class 3: Burnt Substances

However, in order to avoid complete combustion with great loss of substance, it is necessary to stop the process precisely at the point when maximum carbonization is reached. Therefore, recipes suggest that one should directly immerse the burnt material in water. In this wet state the material can be directly ground on a stone or left to dry for later processing. Different burnt substances are described in the sources: (1) vine twigs, (2) paper, and (3) bread.

3.1 Burnt Vine-Related Components [Reconstruction1]

“Another black is made of the tendrils or young shoots of the vine, which are to be burned, and when burnt, thrown into water, and quenched, and then ground like other black pigments.”[*]

Both Cennini and the author of De Arte Illuminandi refer to vine twigs and tendrils, left-overs from pruning.[87] Burning these plant left-overs in order to produce a pigment was a smart method of recycling. Vine twigs can be simply burnt directly at the site, without the necessity of using crucibles. Pruning of vine plants happens everywhere where viticulture is carried out. It is therefore not surprising that Italian authors describe this method. Reconstructions show that burning of fresh vine tendrils and twigs is not as easy as it sounds. After an initial drying process, thin twigs burn quite quickly. Determining the precise time when water should be added is quite tricky, because while some twigs are still unburnt, other parts have already turned to ashes.

3.2 Burnt Paper [Reconstruction][Recipe: Vatican Ms. Lat. 7279 (1600-1650)]

Several sixteenth- and seventeenth-century authors suggest producing pigment from the waste paper of goldbeaters-booklets, which used paper to separate the leaves of fine gold foil. One anonymous author, for instance, points out that pigment might be “made from booklets which contained beaten gold or silver. One should ignite these books with a candle, and let it burn. If they are completely burnt, one should let them fall into a clean bowl with water. Afterwards grind it and let it dry on chalk”; some authors also mention that this specific paper had a red colour, which is true because these papers were coated with red bolus which allowed a colour impression of the gold on red bolus grounds and prevented the gold leaves from sticking to the paper.[88][89][90]

While gold-leaves were certainly to be found in studios of Burgundian illuminators, none of the fifteenth-century treatises contain any reference to black pigments made from goldbeaters paper-booklets or to burnt paper in general. This is remarkable, because gold-leaf was extensively used in Burgundy, already at the end of the fourteenth century, especially for the gilding of altarpieces, interiors, and painting. Thanks to the meticulous administration preserved in the ducal accounts, the trade in fine gold-leaves amongst other artists’ materials is well documented.[91] They were bought from apothecaries situated in Paris, Troyes, and Dijon and were sold as papiers, containing 300 leaves of gold or silver. This material was incredibly popular, and in one year, 16,841 leaves of fine gold were bought. From 1375-1416 a total of 167,591 gold-leaves were acquired, an extraordinarily large quantity. Individual gold-leaves were 8-9cm2, hence the paper booklets (papiers) probably had a somewhat larger size of about 10x10cm. Re-using this enormous amount of wastepaper seems sensible, not least because in the paper was still an import product in the northern provinces. While French and Italian paper mills had existed since much earlier, the first paper mill in the northern provinces was established in Huy, located between Naumur and Liège, in 1405.[92] Uncoated papers might have been reused as paper for writing notes instead of being burnt.

3.3 Burnt Bread (Manchet)

“Broot Swart. Wittenbroot salmen branden tusschen gloeijende kooIen tot dat het geheel swart is, ende vrijvent dan wel fijn op eenen steen ende doet daer bij een halve boon groote sout, met soo veel gestoote gom ende wijn, ende 1aeten dat so een half ure ten minsten vrijven, en strijcken ‘t dan in een schelp en laet het droogen tot dat gij ‘t gebruijcken wilt ende tempert het dan met schoon waeter, en wilt gij het bruijnder set eht met ruijwaeter dat is sloot waeter, en het sal goet wesen.”[*]

Veen describes the use of burnt bread to produce black pigments in De Wetenschap en[de] Manieren, where he mentions the production of ‘Bread Black’: “White bread is burned between red-hot coals until everything is black, and then grind it finely on a stone, and add salt the size of half a bean, with as much pounded gum and wine, and grind it at least half an hour, and then put it in a shell, and let it dry until you want to use it and then temper it with clean water, and if you want it brown, then mix it with the water from the sluice, and it will be fine”.[93]

While unintentionally burnt bread was common and was surely available in fifteenth-century Burgundy, it is unclear when artists discovered it as a source of black pigment. Burnt white bread, also referred to as burnt ‘Manchet’, is frequently mentioned in later sources, but does not appear in any of the pre-1600 recipes for black watercolour pigments. Boogert (1692) refers to a ‘stuck roggen-broodt‘, rye bread.[94]

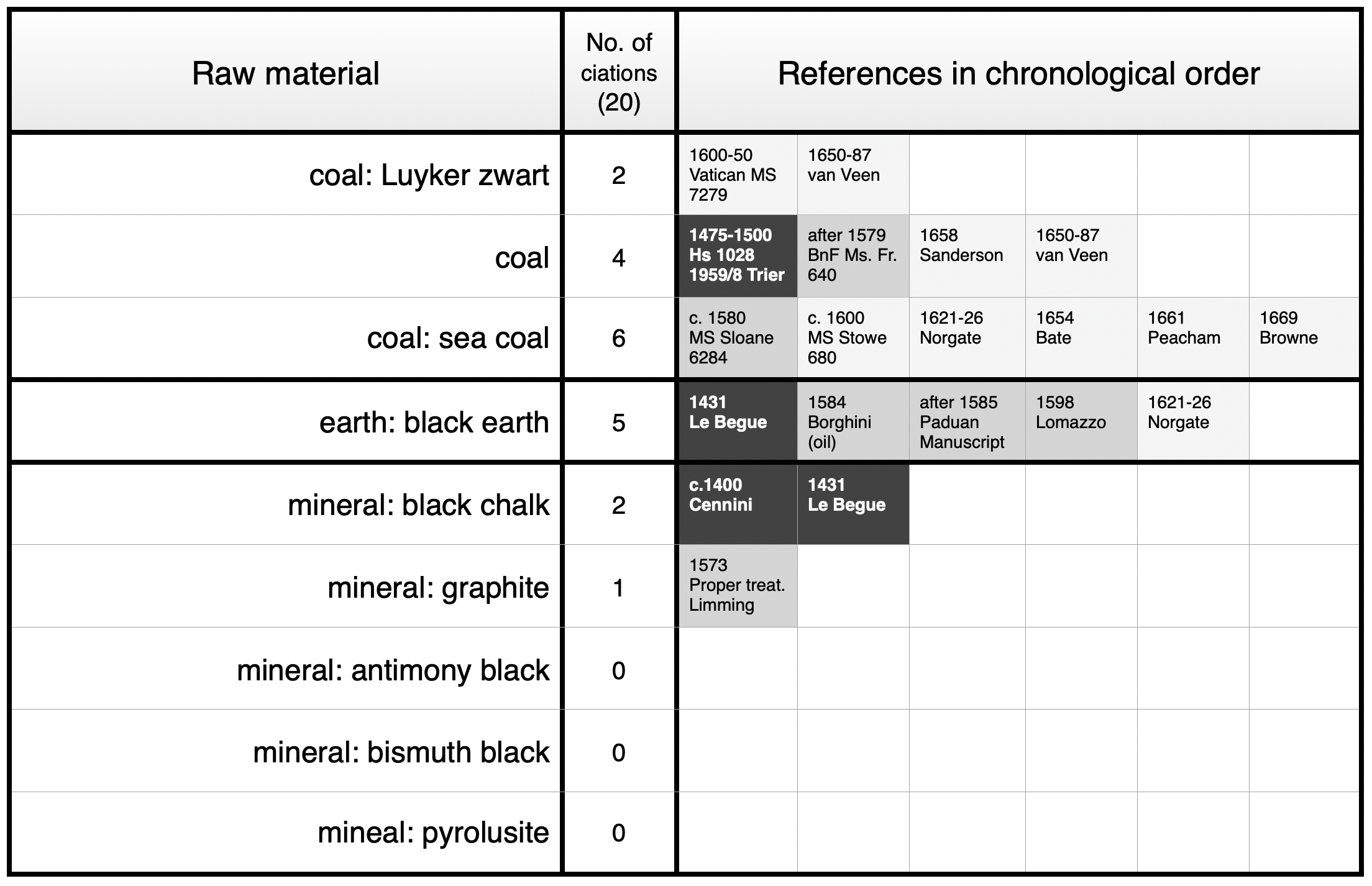

Class 4: Geological Raw Materials

The thin shell on the outside of Earth — the earth’s crust — contains many black-coloured substances. Black coal, which is of organic origin, black earths, and several different inorganic minerals were all used as black pigments. Some minerals even belong to the most ancient black paints used by mankind. The group includes the following raw materials: (1) coal, (2) earths, (3) minerals.

4.1 Coal, Sea Coal, and Luyker Zwart

“Luijcker Swardt. Men maekt oock goet swardt van steencoolen alsmen / die well vrijfft met schoon water, ende verwercken met / schoon gomwater dit is seer bequaem swardt om wullen / laecken mede aen te legghen, ende wordt ghenoemdt smeko / lin swardt.”[*]

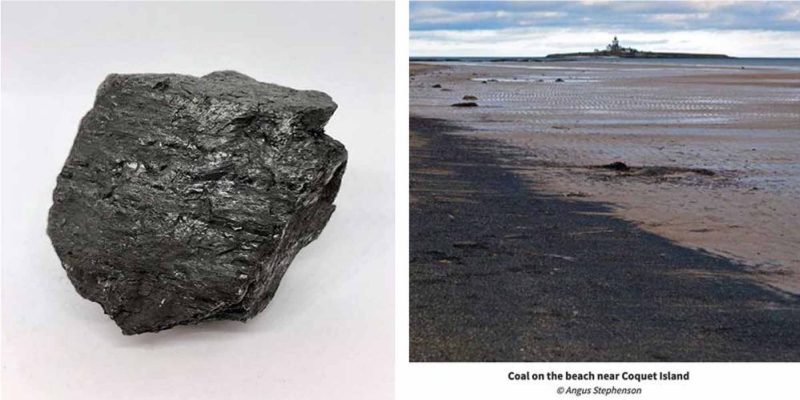

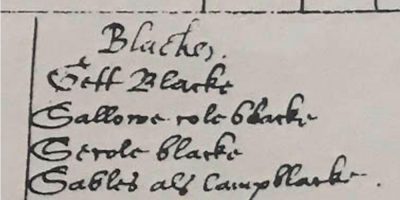

Black pigments made of coal appear in artists’ treatises from the late fifteenth century onwards. They are frequently mentioned in seventeenth-century English sources after English sea coal was introduced to domestic life, as well as in Flemish, Dutch and French sources. Coal is a sedimentary rock, formed from accumulation of plant material in oxygen-deficient swamp waters. Over millions of years, the plant deposits moved into ever deeper layers of the earth’s crust, where they were exposed to high pressure and increased temperatures. This led to carbonization processes, comparable to the act of charring described above. The deeper the coal is deposited, the higher the carbon content . Besides carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, sulfur and nitrogen are also present in coal. Due to the content of sulfur, it’s fumes emit an unpleasant smell during burning. Within Burgundian territory there was an important natural source of coal: the deposits of the Sambre-Meuse valley, which stretched from Mons in the County of Hainaut, via Charleroy and Namur, to the Prince-Bishopric of Liège.

Liège (or ‘Luik’ in Dutch) is the eponym for the pigment Luyker zwart, which appears as a black pigment for limning in two seventeenth-century manuscripts, as in an anonymous recipe which suggests that ‘You can also make good black coal if you grind it well with clean water and process it with clean gum water. This is very good black for painting woolen fabrics and is also called blacksmith-coal black’.[95] Another closely related manuscript from Amsterdam also describes coal black.[96] Coal was mined near the city of Liège already in the thirteenth century, it must thus have been accessible to illuminators active in Burgundian regions. However, the coal’s sulfur content causes interactions with sulfur-sensitive pigments like lead white, inducing colour changes. Such decay reactions were known to illuminators who avoided combinations of susceptible pigments.

At the end of the fifteenth century coal is mentioned for preparation of a black printing ink in a compilation of artists’ recipes written in Oostmiddelnederlands: ‘So wrijft steynkolen myt vasser’ — ‘so grind coal with water’ — suggesting that it was known and available in the northern territories.[97]

A specific type of coal — sea coal — is a British phenomenon, and it was frequently used in the production of black pigments. It is found in the northeastern England, especially in the region around Newcastle. Here, exposed to the seashore, coal seams crop out on the beaches, which explains the name. Adjacent to the coastal area, deposits of coal were found close to the surface. Already in Roman times, coal was mined in England, though the practice disappeared for several hundred years. In the thirteenth century, coal was rediscovered in areas where seawater bared coal deposits. Surface deposits were exploited on larger scale from the fourteenth century onwards, especially around the river Tyne. Initially used by black smiths and lime burners, it replaced wood and charcoal as domestic fuel in English coal districts in the fifteenth century.[98] During the sixteenth century, a considerable demand for coal had sprung up on the continent, with particular demand among French metal processing artificers who were dependent on English coal exports.[99] The final transition from wood to sea coal as fuel in domestic London took place during the seventeenth century, but this transition was met with opposition because of the stink produced by burning sea coal: ‘the nice dames of London would not come into any house or room when sea coals were burned, nor willingly eat of the meat that was either sod or roasted with sea coal fire’.[100] When it came to burning sea coal, some authors worried that it would affect the colourfastness of paintings, ‘for the colours themselves may not endure some Ayres, especially the Sulphurous Ayers of Seacoal’.[101] This warning is not yet included in the first, 1634 edition of Bates’ The Mysteries of Nature and Art‘, but does appear 20 years later in the third edition, when sea coal was established as a commonplace fuel in London. With regard to these developments, especially with the increased availability of sea coal, it is not surprising that the late sixteenth century and especially the seventeenth century mark the period when it first appears in sources as a black pigment.

“Smeekoole swart. Het smeekole swart is niet anders als het geen men van / den smis of brouwers kool met schoon reegenwater komt tevrijve dat men met reedelijk kort gom water moet tempereren en is dan reedelijk vloeijbar / om op verscheije mannieren tegebruijke gegellijck als hier tesien is.”[*]

Several seventeenth-century sources mention smith coal, as in Boogert’s Klaer lightende Spiegel der Verkonst where he explains that “[S]mith coal is nothing else than that of the blacksmith or brewer’s coal; and grind it with clean rainwater; that one must temper with fairly short gum water and is then reasonably fluid to use in several ways, as seen here’.[102] Goeree also included smith coal in his list of watercolours of 1670.[103] Smith coal might refer to both charcoal and coal, since smiths use both. In the case of Mayerne’s manuscript, it is applied as a substitute term for ‘Luyker black’, or coal. The seventeenth-century spread of coal as a pigment likely owed to the fact that coal was growing easier to obtain.

4.2 Earth

4.2.1 Black Earth (Terra Negra, Terra Nera)

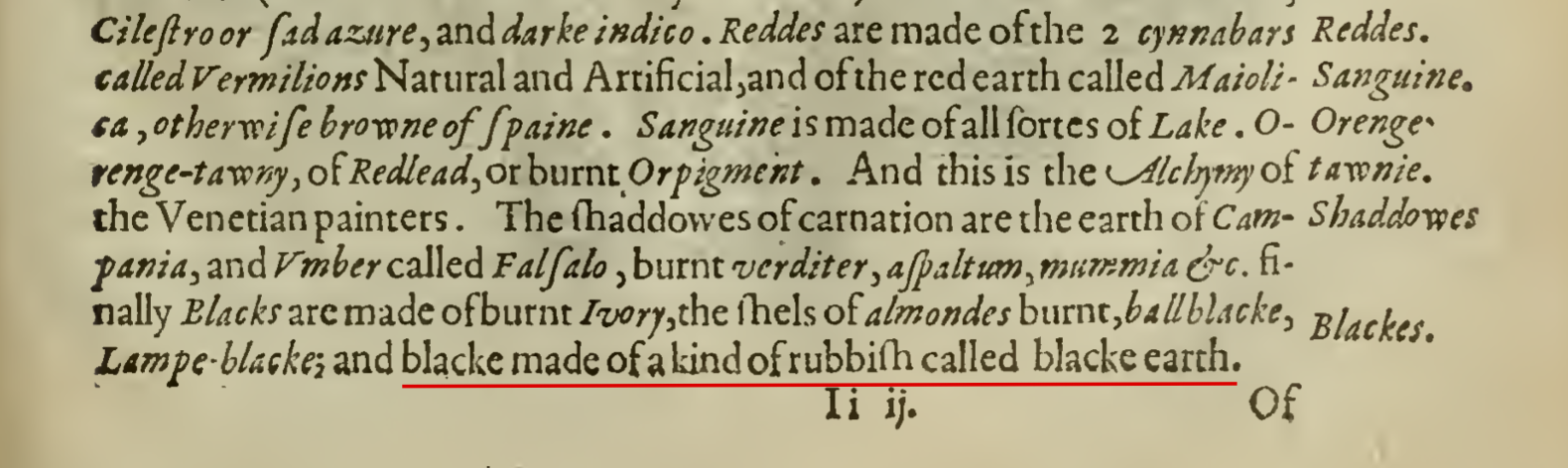

“blacke made of a kind of rubbish called blacke earth”[*]

Already in 1431 le Begue, who compiled many manuscripts of Italian origin, refers to terre nigre, and in 1598 Richard Haydocke continued to refer to ‘blacke made of a kind of rubbish called blacke earth’.[104] It seems to have been an Italian export product. All consulted Italian treatises of the late sixteenth century include terra ne(g)ra, and it was predominantly present as a black pigment in Italian pigment-price lists of the late sixteenth century and throughout the seventeenth century.[105] Amongst the listed black pigments it is even the cheapest. This might explain Lomazzo’s disdain, calling it rubbish.

It seems that Italian black earth was exported to Burgundian territories. While it is not part of the ducal purchases of artists’ materials between 1375-1419, it is mentioned just some months later. For the preparation of decorations, painted flags, and shields for the Troyes ceremonies in 1420, 1/2 pound of ‘Noire terre’ was bought from Collart Le Roy, a mercier.[106] It is questionable if such a cheap black earth was ever applied for one of the most subtle of visual arts, illumination. It is included here since its availability at Burgundian courts is documented in the ducal records.

4.3 Minerals

“Remember that there are several black pigments, one of which is a soft black stone, and the colour is opaque.” [*]

By 1400, Cennini refers to lapis nero, then a new material from the Piemont region, ideal for use as black chalk crayons for drawing.[107] In 1431, le Begue includes lapis niger into his table of synonyms.[108] Black chalk is commonly found close to slate mines and was also applied as a pigment. Apart from ivory black, it is the most expensive black pigment in the aforementioned Italian pigment price lists published by Spear. Slate deposits are present in today’s Belgium. It would be interesting to determine if it was already available to Burgundian artists as a black drawing medium or pigment, or if they imported it from Italy.

“To temper blacke Leade: Grynde well blacke Leade with gumme water on a Painters stone, and then put it in a shell to woorke withal. This is a perfite Crane color of it selfe.”[*]

In the first half of the sixteenth century, graphite was discovered in Cumberland, England, too late for Burgundian illuminators. The first image of a black lead pencil was published by the Swiss scholar Conrad Gesner in 1565.[109] Shortly after, it is mentioned as a black pigment in the first English printed book on limning, the 1573 published “A very proper treatise wherein is breefely set forth the art of limming”. The anonymous author makes the reader aware that the colour obtained is that of the crane, a perceptive observation which is repeated by later authors.[110]

4.3.3 Antimony Black (Kohl, Stibium, Sulfuratum Nigrum)

It is noteworthy that this pigment, while not included in the consulted treatises, was identified in at least two illuminations of different artists active around 1500, namely an Italian miniature by the Pallavicini Master (active in Rome 1492-1507) and in one of five French grisaille miniatures from the Poeme sur la Passion by the Master of Girard Acarie (c. 1530).[111] Antimony (III) sulfide (Sb2S3) is a naturally occurring black-grey coloured mineral known as stibnite. Stibnite is quite common and found in many European mines. It occurs in paragenesis with many other sulfide minerals, such as orpiment, realgar, cinnabarite, pyrite, and barite, all well-known artist materials. The mineral has been known since ancient times and was used, for instance, as black eyeliner, especially in the Arab culture, where it is known by the name kohl. Highly regarded by alchemists, widely used in metallurgy and in medicine, antimony black most probably was available to the Burgundian illuminators.

Bismuth black was identified as granular elemental bismuth in eight illustrations by Jean Bourdichon (1457–1521), an important French manuscript illuminator. These illustrations were spread over three manuscripts dating from the early 1480s to 1515.[112] Bismuth black was not found in the consulted sources as part of an illuminator’s palette. In nature, bismuth occurs either in its elemental state, or in ores of various metals including cobalt, nickel, silver and tin. It is found, for instance, in Schneeberg, Germany and was discussed by Paracelsus and Agricola in the first half of the sixteenth century.

Already used by Neanderthals and found in prehistoric cave and rock art, pyrolusite is a naturally occurring black-grey mineral, and an important ore for manganese. Many deposits are present in Europe. The Montpellier Liber diversarum arcium lists it under ‘De manganese’ as a black colour for glass and ceramics. Pyrolusite was identified in a manuscript initial illuminated in Bologna or Rome about 1490-1500.[113] It should be noted that certain umbers show a high pyrolusite content.

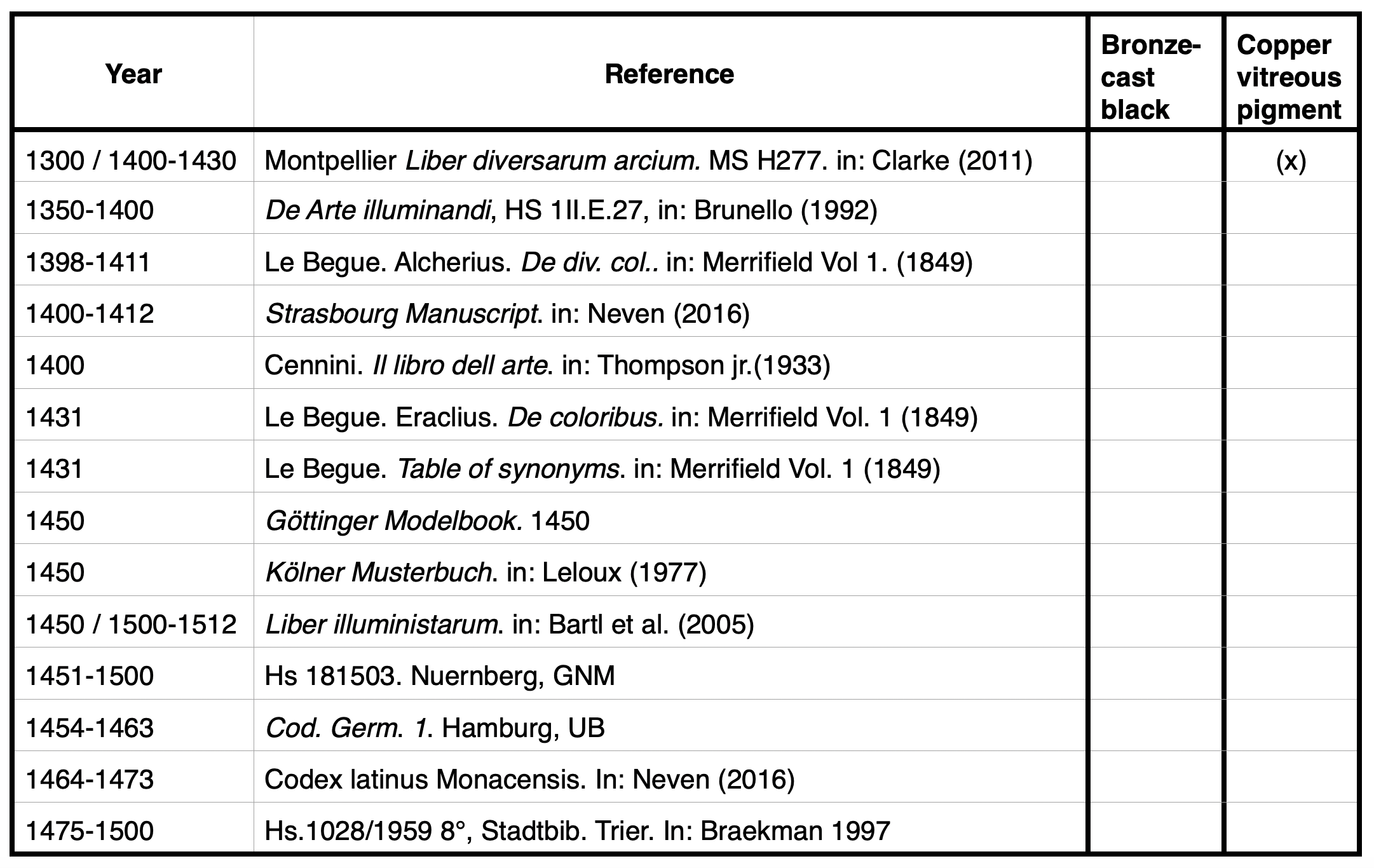

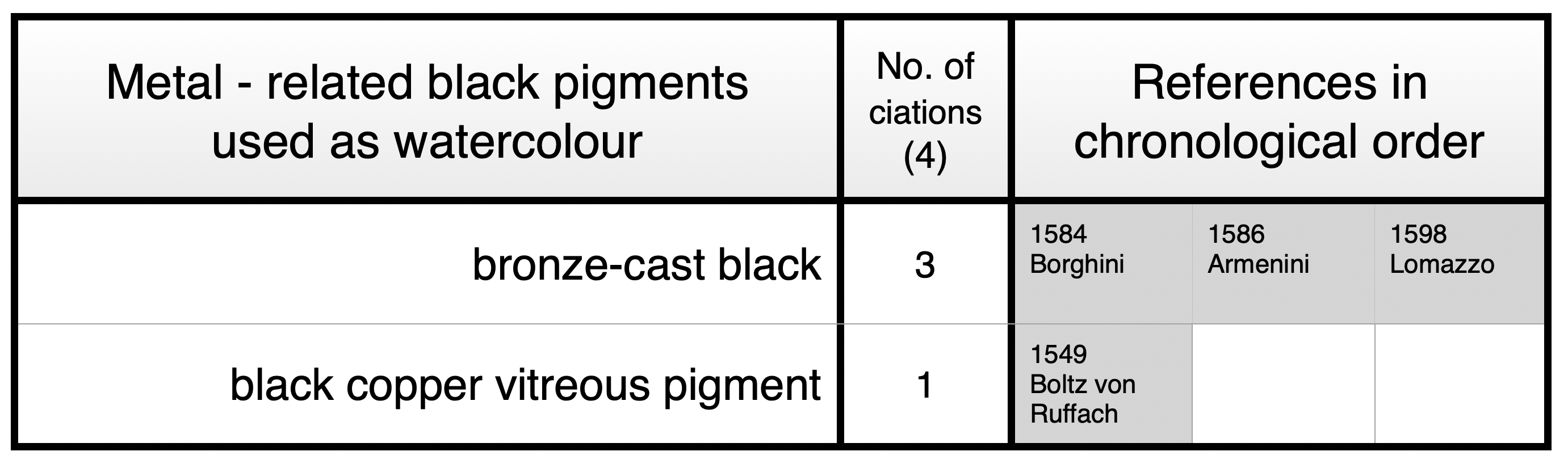

Class 5: Metal-Related Black Pigments

The production of bells and cannons, as well as specific processes of stained-glass manufacture, generated black pigments. These pigments found their way into the ateliers of illuminators, a proof of the close intertwining of different artisanal professions. The group of metal-related black pigments consists of (1) Bronze-cast black and (2) Black copper vitreous pigment.

5.1 Bronze-Cast Black (‘Nero di Terra di Campana‘)

“As experience shows, in the casting of bells, while the metal falls in the earthen mould, it causes a large part of it nearest to the metal to become very black. The painters use this instead of black earth.”[*]

The Mariani-Cibo manuscript, an Italian text on miniature painting dating from 1620, recommends using black pigment derived from waste products of bell casting as an alternative to black earth. There, we learn that, ‘[a]s experience shows, in the casting of bells, while the metal falls in the earthen mould, it causes a large part of it nearest to the metal to become very black. The painters use this instead of black earth’.[114] Other Italian treatises, especially those from the late-sixteenth century — including Armenini’s and Borghini’s — mention the use of a black pigment that is closely related to the ancient art of bell casting.[115],[116]

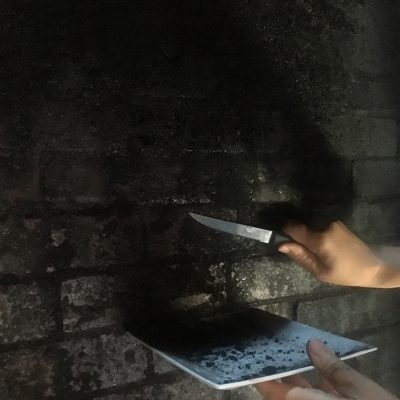

Nero di terra di campana is described as a black-coloured ‘crust’ that is retained after bells and pieces of artillery have been cast. It remains unclear which material precisely is meant here. Most probably it concerns the loam-layer of the mould that directly adheres to the outer bronze-metal of the cast. After cooling down and removing of the outer and inner mould, this layer has to be scratched off carefully by hand. Another explanation could be the introduction of graphite as a coating during the casting process, which rendered the surface of the cast much smoother. The use of graphite was possible just after its discovery and availability in other countries than England, which indeed might have been the case at the end of the sixteenth century in Italy. This new and fancy material might have triggered authors to include it into their artist manuals.

Bell founding was carried out by travelling belleters directly at the church that commissioned the bell. Therefore, nero di terra di campana is quite a unique material, available either at the rare occasion of the founding of a bell, or at certain places, such as cannon foundries. Unanswered remains the question why this specific black is only mentioned in Italian sources and if its use was confined to Italian illuminators only.

5.2 Black Copper Vitreous Pigment

“Von kupfferlott schwartz kupfferlot zu machen. Nim reinen Hammerschlag ein lot, und ein lot kupfferäschen, ii lot schmeltz glaß, daß reibe alles wol durcheinander, biß das es gar keine sandige räuch mehr hab, du solts aber reiben auf einem kupffern blat, temperiers mit Gummi wasser, mit dem magstu alle liechte farben verschattieren, besonder aber weisse farb.”[*]

Ruffach notes the use of black copper as a source for black pigments in his Illuminer Buch, where he explains the process of pigment production: ‘To prepare black copper from copper. Take one lot of pure Hammerschlag [i.e. residual iron particles that remain after forging], and one lot of kupfferäschen [i.e. copper ash, or pulverized black copper (II) oxide, crocus veneris], two lot of ground glass. Grind it all together, until it has no sandy smoke [?], but you should grind it on a copper plate, temper it with gum water, with this you can shade all light colors, but especially white color’.[117]

In the fifteenth century close collaborations existed between various crafts. Glass painters, for instance, adopted techniques from oil painting and the graphic arts, transforming the medieval craft to a high degree of artistic excellence.[118],[119],[120] Glass-painter workshops in Strasbourg were innovative by introducing new graphic elements, and worked from templates by Rogier van der Weyden and Martin Schongauer. Around 1500, designs by Albrecht Dürer, Hans Baldung Grien, and others were executed in glass. This mutual exchange is reflected also in contemporaneous sources on black pigments. In his treatise, Ruffach included a black pigment that was prepared by painters of glass. This pigment is called ‘schwartz kupffer’ or ‘black copper’ and was used as black vitreous paint to draw linear contours on glass. According to Ruffach, as a watercolour, this pigment is of a ‘falb brun’ or ‘brownish’ colour and is as easy to use as the black of soot.[121] Such a glass paint is already recorded in the fifteenth-century Montpellier Liber diversarum arcium. [122] There, the preparation is slightly different, and involves mixing one part pulverized black copper(II)oxide (CuO, crocus veneris, generated by repeated annealing of thin copper sheets and subsequent washing and grinding), three parts of pulverized dark blue glass, four parts of forged iron particles, and a bit of manganese. Due to the use of blue glass, this recipe results in a blue-black pigment. To prepare a watercolour, the black pigment was tempered with gum water. It is reasonable to imagine that Burgundian illuminators knew about vitreous paints, but how far they applied these pigments for their own work requires further research.

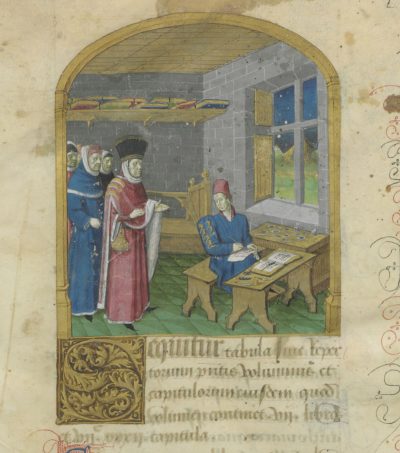

Class 6: Black Inks and Dyes

In general, Burgundian scribes and illuminators were members of two separate professions. While ink was, of course, indispensable for scribes as they cared out their writing, copying, and calligraphy, it might appear somewhat surprising that it also belonged to the common palette of illuminators. That the borders between the professions were porous is shown in one of the rare miniature paintings that depicts an illuminator in his study [Figure 43]. His writing paraphernalia are spread on the table in front of him: goose quills, a knife, a sander, and his calamal, a portable container to safely carry writing instruments and the inkwell, which is worn on the belt. It makes sense that his implements for illumination are safely placed on a separate table to is left side below the window.

Diluted ink was widely used for first drafting the contours of a design. In addition, ink was used for shaping outlines or particular features in illuminations, as well as to achieve the finest details in the marginal decorations. Paint mixtures could include inks to achieve specific shades, for instance a grey colour. Around 1500, an anonymous author advised to mix the same amount of red paint with good ink to achieve a grey colour: ‘Take a lot of good rubric and good ink, put them in a horn and let it stand for a night’.[123]

Inks played a prominent role in the specific genre of miniature painting in grisaille that flourished under Burgundian reign. Phillip the Good’s book of hours, created between c.1450-1460 is a famous example of grisaille of the Burgundian era. Written by Jean Miélot, secretary of the duke, most of the grisaille illuminations were created by Jean Le Tavernier. Another Burgundian illuminator, also famous for his grisailles, was Jean Dreux, Philip the Good’s valet de chambre, who was active as an illuminator between c. 1430-1467.

Inks could be used in concentrated or diluted form. Major types of black ink that were used as black pigments were: (1) soot-based inks, (2) India inks (3) iron-gall inks, (3) mixtures of both, and (4) dyes.

6.1 Carbon-Based Inks

6.1.1 Soot Inks [Recipe: Codex Germanicus 1 (1454-1463)][Recipe: Andriessen (1552)]

Inct ter noot te maeken Dat vierde Capittel. Ghi sult nemen ene Was caersse ontsteectse ende holtse tegens een becken oft schottele tot dat vanden roock roet oft swartsel daer an / hange. Giet dan een weynich warm Gom water daer in ende tempereerts doer melcandere soe ist incte.[*]

The extremely fine particles of soot make it an ideal pigment for inks. Similar in composition, soot-based watercolours and soot-based inks cannot be differentiated. The application method and the final end product determine the attribution to one or the other – a written document would point to a soot-ink and a painting to a watercolour. Soot-based inks predominated in Islamic and Sephardic writing traditions, as well as in far Eastern cultures. While they were, and for calligraphy still are, widely applied with reed-pens and brushes, their use with quills was less habitual.

Pre-modern European ink recipes usually refer to soot-based inks as inks ‘to prepare in exigency’, usually if iron-gall ink was not available. To do so, one should ‘[t]ake a wax candle, light it and hold it against a bowl or a dish until soot or the black from the soot sticks to it. Then pour a little warm gum water into it and temper it so it’s ink’. [124]

Such ink could be easily produced anywhere, which was useful for traveling. If ink was required, the smoke of a candle was collected onto a dish and mixed with dissolved gum arabic or other binding media, such as egg white. The composition of the candle could vary from a cheap tallow candle, to a wax candle as in the above cited recipe, and might also be created with a self-made candle from pitch/tar, as an anonymous author of the mid fifteenth century recommends, as in a recipe from the Codex Germanicus: ‘If you want to make a black ink, take and make a candle with pitch. Light it and catch as much smoke as you want in a basin. Then take the soot and mix it with gum water and let it dry. Use gum water to prepare the ink. It is good and does not harm the eyes’.[125] For illuminators, soot-based inks would have been easy to apply either with a quill or with their super-fine brushes, diminishing any proper distinction between watercolour and ink.

“Oosstinjenhen ink. Aan den oosstinjenhen ink en hooft men niet anders te doen als dat men die self met wat schoon regen water over de steen gaet vrijven waer door se genogh of sal gaen omte gebruijcken of men leijt den stuckje daar van in wat schoon regen water tesmelte met den weijnigh gom oock wel sonder gom en als dun kan men die gemackelijck en op verscheije mannieren gaan gebruijcken gelijkck als hier tesien is.”[*]

India ink became popular as soon as trade brought this product to Europe. Many seventeenth-century limning manuals refer to India ink. The ink was sold in hard sticks which required rubbing on a stone with water to release the intensely black ink. The use of brushes for Chinese and Japanese calligraphy might have inspired the use of India ink as a watercolour in Europe.

For centuries, and despite frequent attempts, Europeans were unable to replicate the dark and rich ink that was imported from China and Japan. Sources warn against fake India ink and include advice on how to test its quality, as in the complaint of Michael Bernhard Valentini in 1704: ‘[t]he Dutch imitate it today, but nowhere near as beautifully and well. The difference can be recognized in so far that that the Dutch looks grayish- black and consists of flat pieces, whereas the real Chinese comes in beautiful shiny black and in finger-thick pieces’.[126]